An amazing discovery from the good folks at the Internet Archive. Visit the Off Bunker Hill list, where LA historians and former Bunker Hill residents have been identifying structures and dating vehicles. One person even thinks they’ve spotted their father leaning on a lampost!

Tag: 300 Block

Two New Mann Images – Final Days of the Flight!

Hillzapoppin‘ in the OBH! A couple swanky new color images emerged from the greater Mann grotto and the good people at the archives wanted to share them with you. Ain’t they the best?

This image is later than the other Manns (Menn?) we’ve seen. (Given the specific progress made on the Union Bank tower, I’d peg this photo at September 1966). By comparison, here’s one of late-50s vintage you’ve seen before:

The Community Redevelopment Agency got their wreckers and worked from top to bottom; started with the Elks in the autum of 1962, then hit the Hulburt (middle) and finished the Ferguson on Hill in ’63.

With Angels Flight’s Western Wall removed, you then see these two characters in images of the Flight, but they were chewed up pretty quickly.

But back to our original Mann photo up top. To the east of the flight on the other side of the tunnel, the Royal Liquor’s still there, and so’s the McCoy house above.

Royal Liquor–AKA St. Helena Sanitarium–always amuses because before Los Angeles became last refuge for the hunted and the tortured, it was just a sunny place to go for salubrious living:

Now let’s cross the intersection, down Hill a bit…

…turn to see that Olivet and Sinai have passed each other. The Hill Crest and the Sunshine, of whom we’ve spoken quite a bit recently, gone, again, the CRA working down from Olive to Clay, the HillCrest lost in the autumn of 1961 and the Sunshine goes ca. 1965. There’s the McCoy House and St. Helena, although now the latter, known as My Hotel for some time, became the Vista Hotel between 1942 and ’47 (and the actual full name of its corner booze boutique, despite what the neon read, was Royal Gold Liquors). Vaguely visible looming behind in the mist, the Belmont.

The former front door of the Ferguson Café apparently a swell place to park your faded yellow jalopy. In September of 1966. Now, not so much.

Hey, at least the light pole and fireplug are still there.

Thanks to George Mann’s son Brad Smith, and daughter-in-law Dianne Woods, for allowing us to reprint these copyrighted photographs and tell George’s story. To see George’s photos of theater marquees, visit http://www.flickr.com/photos/brad_smith

For a representative selection of photographs from his archive, or to license images for reproduction or other use, see http://www.akg-images.co.uk/_customer/london/mailout/1004/georgemann/

St. Helena/Vegetarian Café, USC Digital Archives; Ems & Casa Alta, personal collection

Sunshine and Noir

The recent release of George Mann”™s 50-year-old color photographs to this site is one of the most remarkable troves of

Bunker Hill”™s Sunshine Apartments at

Constructed on vacant property around 1905 to accommodate downtown Los Angeles”™s growing need for cheap housing, the Sunshine looked like a huge clapboard farmhouse, with a stack of three unadorned verandas and a couple of Queen Anne touches around the front entrance, which was on the third floor. Midwestern migrants probably found the place comfortably familiar. Inside, a labyrinth of odd-angled hallways, step-downs and staircases connected the Sunshine”™s many small apartments.

Though it made its film debut as one of Angels Flight”™s neighbors in a 1920 comedy called All Jazzed Up, the Sunshine didn”™t get its first close-up until 1932, when director James Whale cast it as the home of two downtown working girls (Mae Clark and Una Merkel) in The Impatient Maiden, his follow-up to Frankenstein. Because sound cameras in those days were large and unwieldy, he used a smaller silent camera to shoot the movie”™s opening scene on the

But what turned the Sunshine Apartments into a fairly steady (if nameless) character actor was film noir, the mostly post-World War II crime genre that, in its focus on documentary realism, introduced the use of smaller, combat-tested cameras and gritty urban locations to Hollywood cinema. And since–by the mid-1940s–

In

That same year, in Universal Pictures”™ Criss Cross, director Robert Siodmak used the Sunshine as a rendezvous spot for criminals plotting an armored car robbery. Whereas the protagonists”™ apartments in the earlier films were obviously studio creations, some of Criss Cross”™s seedy flophouse interiors were shot on location. Granted, a couple of shots that showed either Burt Lancaster or Yvonne DeCarlo standing next to a bay window, with the Angels Flight trolleys moving in the background distance, were done on a sound stage. The footage of the incline railway cars passing each other above Clay Street was taken from the Sunshine (most likely from the third-floor porch, judging from the angle), but the building itself didn”™t have any bay windows facing Angels Flight, so the scenes had to have been process shots. On the other hand, the maze of dingy hallways–whose atmosphere one character mockingly dismissed as “Picturesque, ain”™t it?”–most likely belonged to the Sunshine Apartments.

In another

In the low-budget Angel”™s Flight (1965), among the last of Bunker Hill”™s noirs, Indus Arthur played a stripper and “

The building also showed up briefly in Act of Violence (MGM, 1949), Joseph Losey”™s M (

The Sunshine Apartments finally had its appointment with the bulldozer around 1965, after

Yet today the Sunshine Apartments survives in old movies, in countless photo- and postcard-tableaux of Angels Flight, and as the most prominent background feature–painted green–in Millard Sheets”™ vibrant 1931 oil painting, Angel”™s Flight, which is not only one of the most famous works on permanent display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, but also the logo of the OnBunkerHill.org website.

I welcome any further information you may have about the Sunshine Apartments, or any corrections to this blog entry. Even better, I”™d love to hear from someone who actually lived or spent time there.

For more photos of the Sunshine Apartments, check out www.americanfilmnoir.com/page18.html and www.forum.skyscraperpage.com/showthread.php?p=4855115.

Thanks to George Mann’s son Brad Smith, and daughter-in-law Dianne Woods, for allowing us to reprint his copyrighted photograph.

For a representative selection of photographs from his archive, or to license images for reproduction or other use, see http://www.akg-images.co.uk/_customer/london/mailout/1004/georgemann/

The Ems – 321 South Olive

In what will surely go down as the smarmiest piece of journalism in history, the Times recounts the travails of Toy Lane, dancer at the Chinese Junk, 733 North Main. She made her way over to the Junk from her pad at The Ems to shimmy for shekels on September 25, 1946. When she gets into the nightclub dressing room to “dress” for her act (the Times‘s flippant application of quotation marks, not mine) she discovers her wardrobe has been stolen: G-string No. 1 (black and orange, beaded,) $35; G-string No. 2 (silver metallic cloth,) $23; beaded shaker, $20; rhinestone brassiere $20; an anklet and armband set, $25.

Miss Lane, it was reported, was mortified–she had to dance with her clothes on!

In a final piece of facetiousness, the Times noted “the police were searching for the burglars and the large van they must have used to carry away the loot.”

The Chinese Junk Café:

Which was up in China City, a 1935 Chinesque development that predated New Chinatown, and had been the baby of wealthy socialite and “Mother of Olvera Street” Christine Sterling. China City was mostly burned out, literally and figuratively, by the early 50s.

And of Ms. Toy‘s home, the Ems?

Remember the Palace/Casa Alta post, which was long on storytelling but short on pretty pictures? I even chided you for looking at a structure that was not our hotel-in-question, by tossing über-comely Bunker Hill lass The Ems smack dab into the mix.

I even promised I‘d talk about the Ems “next week,” but by next week it was President‘s Day, and somebody had to make you mindful of your nation, despite all the patriotic work you were doing watching Obama informercials.

Well, now it‘s the week after next, and it‘s time for the Ems, which is replete with pretty pictures but sadly short on storytelling. Here‘s what we know.

Charles Clayton Emswiler came to LA in the boom eighties and went into the apartment-house building game. In August of 1905 he pulled permits to build his eponymous Mission-style Ems, designed by none other than Joesph Cather Newsom. Emswiler died in 1922, age 69, in the apartment house at 321 that bore his name.

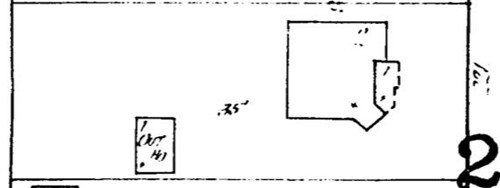

It contains 110 rooms, divided into twenty-six apartments according to the 1939 census, sixty-five apartments according to the 1950 Sanborn map. Here it is before its birth, from the 1896 Sanborn map (321, bottom), and postnatal from the 1906:

Our earliest known shot, above. Pre-1908, because the Kellogg has yet to be built to the north. Notice the three round-arch traceried windows along the street, and the turreted house to the south.

We know that it had a large ballroom, for in 1909 the papers announced that sixty couples participated in the dancing at the inaugural ball honoring President Taft.

The Ems were apartments-of-choice for a collection of colorful characters.

1914. “Mohawk Half-Breed” Daniel T. La Rae, alias Daniel T. Ray, was an Ems resident (Emsident?) with Miss Emma Ewalt–they stayed there together, but were (!) unmarried. Daniel spent a lot of time promising to marry Miss Ewalt, even going so far as to travel to Shelby, Ohio, to visit her father. Mostly what Daniel did, though, is borrow money–he needed these sums to purchase marble on bond to build post offices and such. Of course he could be trusted; he was a Federal Officer, after all.

He had shown Emma a badge emblazoned “U. S. Marshal,” but never paid back the money nor made good on his promise of marriage. Of course his badge was a phony as his promises. Turns out his real job was for the Southern Pacific RR, guarding Chinese as they were ferried from San Francisco across the Mexican border line. Chinese actually go home to Mexico. Little known fact.

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse, 1840 Lebanon. The liquor was valued at $40,000. In addition to the liquor, the drys seized a large truck, three touring cars and several rifles.

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse, 1840 Lebanon. The liquor was valued at $40,000. In addition to the liquor, the drys seized a large truck, three touring cars and several rifles.

Above, the Ems in 1912 and a William Reagh image ca. 1960. Notice the rounded tripartite fenestration, which worked so well with the rest of the façade, has been changed to a single remaining arched window, a square window, and a doorway. This is due to owner William Fisher’s February 1927 alteration–he hires architect B. N. Rickard, of whom you have never heard, and rightfully so, since this is pretty clunky work, to convert the lobby into two bedrooms and turn the ball room into a new lobby. (Note too that the neighboring house–built in 1887-88 by Howard W. Mills, of real estate firm Mills, Crawford, Pauly & Clapp–at 327 South Olive has been reduced to a concrete pit, demolished for a parking lot in the summer of 1948. )

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to 903 West Twenty-First St. to fill a position as a mother‘s helper. As soon as she got the job, she was attacked by mother‘s son James D. Anderson. Erma wasn‘t the first to have met with the fate of an Anderson Employee–one Marguerite Cooper, 23, also testified with Erma in Municipal Court about a similar sitch, and the Judge ordered Anderson held on $10,000 bail.

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to 903 West Twenty-First St. to fill a position as a mother‘s helper. As soon as she got the job, she was attacked by mother‘s son James D. Anderson. Erma wasn‘t the first to have met with the fate of an Anderson Employee–one Marguerite Cooper, 23, also testified with Erma in Municipal Court about a similar sitch, and the Judge ordered Anderson held on $10,000 bail.

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at 30th and Broadway, when he fatally struck Mrs. Marianna Valenzuela, 58. Hey, I warned you that the Ems lacked gripping and protracted tales. But look at those pretty pictures.

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at 30th and Broadway, when he fatally struck Mrs. Marianna Valenzuela, 58. Hey, I warned you that the Ems lacked gripping and protracted tales. But look at those pretty pictures.

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the Belmont had two in ‘42). It‘s easy to posit that the suicide rate is a constant, and the papers make a point of reporting ”˜em during wartime to detract the populace from all those incoming body bags. If you go for that sort of mass-media-control conspiracy. That notwithstanding, nine months after we got into the war, Joseph Buotha, a 58-year-old former private investigator, ate several bottles of pills in his Ems apartment. He had just written a long telegram to Eleanor Roosevelt, and this note: “Please let me alone. Let fate take its course. Notify John G. Wenk to take care of my belongings. Please don‘t hurt the dog. May God forgive you.”

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the Belmont had two in ‘42). It‘s easy to posit that the suicide rate is a constant, and the papers make a point of reporting ”˜em during wartime to detract the populace from all those incoming body bags. If you go for that sort of mass-media-control conspiracy. That notwithstanding, nine months after we got into the war, Joseph Buotha, a 58-year-old former private investigator, ate several bottles of pills in his Ems apartment. He had just written a long telegram to Eleanor Roosevelt, and this note: “Please let me alone. Let fate take its course. Notify John G. Wenk to take care of my belongings. Please don‘t hurt the dog. May God forgive you.”

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

There‘s that railing! The railing of DEATH!

Ok, the railing of death. It‘s not much, but it‘s something.

Of course we know how the story ends. The Ems gets its demo permit pulled in July 1965. By the summer of ’66 it’s just a pile where a truck can pull up, while erstwhile neighbor the Casa Alta is undergoing a similar fate:

After the last few posts–piles of brick, crenellated castles, Neo-Classical noodling–I am happy to say look at all that stucco (stucco that‘s supposed to be there, not stucco that was thrown over shingle–although to be honest, it wasn‘t thrown over adobe brick, either). The deep arcades, the rounded arches, the low-pitched red tile roofs”¦Mission Revival sure oozes picturesque. Were the square flat roof to call a California antecedent to mind, you might think of the 1894 Burlingame train station.  The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish St. Regis.

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish St. Regis.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

When it comes to architecture important to this part of the world, it can be argued that Spanish Colonial/Mission Revival is our own honest, expressive flowering, that‘s crowd-pleasing but not childish, sometimes silly but never stupid, hard to notice sometimes and often hard to preserve.

It‘s sad to lose Bunker Hill in general; we’re sorry to lose the Ems in particular.

Early shots, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; later b/w shots, William Reagh and Arnold Hylen Collections, California History Section, California State Library; color shots, Walker Evans, “439 Architectural Views for Time-Life Project ‘Doomed Architecture'”, metmuseum.org

The Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta–317 South Olive

May 22, 1930

William J. Stone, 38, was a Bostonian broker who’d moved to Los Angeles and into the Casa Alta Hotel and Apartments, 317 South Olive. In what may have partly been a case of Don‘t Argue with a Janitor, or partly No-One Likes a Broker in 1930, Stone managed to get into a regrettable debate with the Casa Alta janitor, one Walter Dixon.

The argument climaxed in Dixon taking a hatchet to Stone‘s head and chasing him from the building. Stone wound up in Georgia Street Receiving Hospital with severe skull lacerations, but lived to broker–or, not–another day, and Dixon landed in the stir on suspicion of ADW.

Here‘s everything you didn‘t know you needed to know about 317 S. Olive, aka The Kellogg, aka the Palace, aka the Casa Alta.

First of all, there are few photos of the place. Pity the poor Palace. It was too large and utilitarian to merit the lens of a Reagh or Hylen. Sure, everybody shot its neighbor, the Ems, and in nearly every Ems image, there‘s the Great Wall of Alta looming in the background:

(Don’t look at the Ems. Look at the building behind it. We’ll talk about the Ems next week, I promise.)

Moreover, whenever one stood on the corner of Third and Olive, the temptation was apparently too great to turn one‘s back on the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta and shoot the upper terminal of Angels Flight.

Before the advent of 317, it was 315 S. Olive, which was ground zero for the Burning Bushers.

Then came the seven-story, 84-apartment Kellogg. It opens in April, 1908.

Almost immediately it becomes the Palace Hotel and Apartments; the image at the top of this post, where it’s proudly emblazoned Palace Hotel, is from a card postmarked 1910.

Looking up Olive, ca. 1915: the most prominent, in ascending order, the Auditorium, the Trenton, the Fremont, and at top, the Palace:

In 1926 the owner puts it out to lease–it is snatched up and becomes the Casa Alta (they have cleverly renamed this rather tall house "tall house," but in Spanish!).

The 1929 City Directory:

Here‘s what we glean from this 1939 census report: the Casa, faced in brick, has 72 apartments (ok, so the Sanborn Map says 84) in its seven floors, and no business units. There‘s no basement. It was built in 1906, though that doesn’t exactly jive with its April 08 opening date. A nice two-room unit will set you back $27.50 ($406.55 USD 2007), still pretty cheap, but the Hill had begun its downturn even by 1939. Slouching toward shabby though it may have been, nevertheless, that rent was for a furnished apartment, and included heat, water, and electricity.

The 1956 City Directory:

…quite a few folk in the 72 apartments had ”˜phones. Two basement apartments, an office, eighteen tenants had the device. For Bunker Hill, that might have been some sort of record.

By 1965, there were fewer.

And that’s the last time it appears in the directories.

Here it is as one of the lone survivors, in its final days, ca. 1967. Angels Flight hangs on until 1969.

The Palace of Casa Kellogg, and its events of eventful eventfulness:

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace.

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace.

1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of Hotel Clayton (a literal stone‘s throw east at 310 Clay), Florence Cheney, testified. Florence Cheney‘s daughter, Margaret Emery, had her deposition taken at her Palace Hotel sickbed.

1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of Hotel Clayton (a literal stone‘s throw east at 310 Clay), Florence Cheney, testified. Florence Cheney‘s daughter, Margaret Emery, had her deposition taken at her Palace Hotel sickbed.

Margaret testified that Maude Kennedy had been in a fine and jovial mood until very shortly before her death, lending weight to the argument that she committed suicide (Tugwell eventually served ten years in Quentin for manslaughter).

Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas.

Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas.

We‘re all aware that every so often, people sometimes just up and go missing. Dr. Harold E. Roy was a prominent New York dentist whose crushed canoe was found in the Hudson River (it was assumed he was torn asunder by a paddle steamer); his widow moved to Los Angeles and into the Palace Apartments. Then, a year later, in February 1922, a lowly workman at the Kansas City Union Station realized, hey, I‘m a dead New York dentist. Where‘s my wife?  He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

The Palace Hotel/Casa Alta was also the center of political activity for rebel rousers from Riga. Through the late 20s the papers were peppered with small notices about, for example, the precise method of sending packages to Latvia, and if you had further questions, contact the Latvian Consulate–317 S. Olive.

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha!

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha!

![]() November 4, 1929. George McRoy, 31, was spraying the Casa Alta with insecticide–and nearly went to exterminator Elysium, but ended up at Georgia Street Receiving.

November 4, 1929. George McRoy, 31, was spraying the Casa Alta with insecticide–and nearly went to exterminator Elysium, but ended up at Georgia Street Receiving.

“I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death.

“I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death.

Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the Equitable Building, from where she made her own impression on Hollywood.

Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the Equitable Building, from where she made her own impression on Hollywood.

Two items were found in her pocketbook–a letter asking that her nephew be notified, and her eviction notice.

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34?

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34?

We may never know. All we know is that she was recently reconciled with her estranged husband, Willid Thompson. After two years she had returned to him, and for the past two weeks she and he were in domestic bliss at 317 S. Olive. That was, until, April 16, 1948.

Beatrice and Black knew each other from their place of employ, she a waitress, he a cook, at a downtown restaurant.

The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”

The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”

The Thompson killing by Black, who was black, gets surprisingly little press. Perhaps the concept that this interracial killing was presaged by an interracial love affair meant that propriety demanded ignorance.

As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

A month later, December 20, 1952, residents heard screams from the apartment of Willie Kohl, 79. His apartment was aflame; he was found on the floor near the bed, and died en route to Georgia Street.

Kohl’s conflagration is the Casa Alta’s final appearance in the Times. The remaining tenants are relocated in the late 60s and it soon becomes a tall pile of brick.

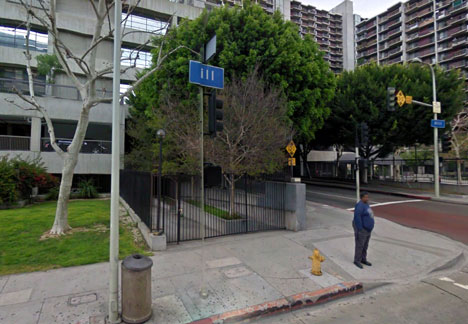

And atop the old site, the 1990 Omni Hotel, in which one can sense a vague hint of the old Alta. Vaguely.

Washington hatchet from here; bloody hatchet from Hatchet; Palace postcard, author; 1910 Ems, Los Angeles Public Library; 1960 Ems, Metropolitan Museum of Art; view up Olive, USC Libraries Digital Archives; census card, USC Libraries Digital Archives; Casa Alta with Angels Flight, Los Angeles Public Library. Bottom image you remember from Subject: Narcotics.

Bunker Hill: A Desperate Race of Men

Hats off to those contemporary “pulse-pounding” pictures what depict early-fifties dope and/or early-fifties Los Angeles for they are certainly the tingliest of films, though, let’s face it, they will never match the breathless, depthless pleasure of going straight to the source, of going straight to the Subject: Narcotics.

Subject: Narcotics. Though no movie critic has ever heard of it, Subject: Narcotics is the Greatest Film Ever Made. Do not confuse this film with Narcotics: Pit of Despair (also the Greatest Film Ever Made) or even Narcotic, which is no slouch either.

Let me say at the outset, unless you are a representative of our law enforcement community, you are not allowed to view this film:

So feel especially naughty in watching it, like sneaking into an R-rated picture when only sixteen. (Believe me, if the Narcotic Educational Foundation of America and their pal Lt. Ray Huber of LA County Sherrif’s Narcotic Detail were asked if the general public should be allowed to view this in fifty-eight years, they‘d say no. No.)

This picture has everything–prosties, junkies, pushers, neon signs:

LA: one big shooting gallery.

He lives from fix to fix and if he is lucky, he dies early, maybe from an overdose, maybe from an infected needle.

Shifty characters plan nefarious deeds on Court Street:

Til the coppers roar upon the scene:

The last part of the picture concerns a hype that gets sprung from stir, only to wander the rain-slicked streets of Bunker Hill (and be passed by a Roadmaster fastback):

He passes by the industrial heart of the Hill, Fourth and Olive —

And we turn and look behind him up to Third and Olive. Looming large and tall in the far distance The Palace Hotel, aka the Casa Alta, aka the Kellogg, at 317 S. Olive; below that, just at his shoulder, the Ems, at 337, and to the far left, the Olive Inn at 343.

Narcotics have weakened his character. Ninety-nine out of 100 slip back.

Alright already. Go watch Crime Wave.

And don’t tell Ray Huber what’s going to become of society.

Love(joy) and Death – 529 W. Third

1947project readers may remember this addition that King of Historians Larry Harnisch made to the blog back in its earliest incarnation. It‘s the story of Gerald Richards, and, because you can read the story in full in the link, I‘ll just toss out the particulars:

1947project readers may remember this addition that King of Historians Larry Harnisch made to the blog back in its earliest incarnation. It‘s the story of Gerald Richards, and, because you can read the story in full in the link, I‘ll just toss out the particulars:

Gerald Richards is 19, and he hasn‘t much in the world. He has a .25 auto that he picked up in Japan during his tour in the Maritime Service, and he‘s got George Kirtland, 24, who he picked up in New Orleans during his postwar wanderlust. It‘s 1947 and they‘ve landed in Los Angeles–George is from Gardena, Gerald an Illinois boy–and George goes to visit Gerald at his digs in the Biltmore. Gerald should have probably chosen somewhere less tony, because his argument over the $32 hotel bill resulted in his shooting the assistant manager in the lobby. Once nabbed, he also copped to two more slayings–a Tom Nitsch in New Mexico, and LA‘s own 52-year-old tailor Charles Vuykov, whose nude body was found on the floor of his room, 529 West Third.

In the 47p post, Larry made mention of the manner in which the Times heads off homosexual implications in Richards‘ Kirtland relationship; but then, what was 19-year-old Gerald doing in the apartment of a 50-something tailor? Especially a nude one?

And let‘s not let this particular address of Vuykov‘s slip by”¦529 isn‘t just any spot on West Third. That shot reverberated across the four corners of Third and Grand. That‘s the Lovejoy Hotel.

The Lovejoy is announced May 1903:

142 rooms, divided into 78 apartments, it opens in November.

It is immediately the scene of many a large society wedding, and home to the known (William O. Owen lived at the Lovejoy when it was finally decreed, in 1927, that it was in fact he who first reached the summit of the Grand Teton).

The Lovejoy is also a hotbed of lefty activity. It‘s a center for the Equal Rights League and magnet for suffragists of various stripe. It‘s where Professor Flinn‘s “physical culture” class met in 1904. It also serves as the 1930s home for the American League Against War and Fascism.

Above, looking north/east on Grand. (Nice crenellated parapets. Despite being against war, its residents were probably glad for defensible battlements.)

Now you see Angels Flight Drugs:

Now you don’t:

This being Third and Grand, the Lovejoy was also across the street from the Nugent. Below, the Nugent is on the left, and we peer down to Olive…there’s the top of Angels Flight, its neighbor the Elks Lodge, and the Edison/Metro Water Bldng at Third and Broadway in the distance.

And, in our continuing effort to get you oriented, endless maps.

From the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, 1906:

From the Birdseye:

From the Baists Real Estate Atlas, 1926:

And of course, the WPA model from 1940:

Above, the Nugent has lost the top of its tower. And is also apparently falling over.

The Lovejoy stands strong, though painted yellow, as per its reputation for hosting pacifists.

The 1960s saw its demolition, and in its place, in the early 80s, the erection of a similarly formidable fortress, Isozaki’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Through true to the Hill, it’s styled less like a castle than it is bunker-like.

Lovejoy images, from top to bottom: author; William Reagh Collection, California History Section, California State Library; Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library; William Reagh, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; William Reagh, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

Lady McDonald Residence – 321 South Bunker Hill Avenue

The 300 block of South Bunker Hill Avenue was supposedly one of the most picturesque in the neighborhood, if not the city. We have already taken a look at the mansions located at 315, 325, 333, and 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue. Now we are going to find out a little about the house with the address 321, also known as the Lady McDonald residence.

Numerous structures on the 300 block of South Bunker Hill Avenue were constructed in 1888, which may or may not be when the McDonald residence was erected. The Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1888 (shown below) does not identify the home as “being constructed,” yet it is a mere shadow of the elaborate structure pictured on the 1894 Sanborn map (also pictured below). Please note the existence of a luxurious outhouse on the property in 1888, which by 1894 has been replaced or converted (yuck) into a guest house.

Even though neighborhood locals referred to the house for decade as the “Lady McDonald Residence,” the earliest known owner of the property was a fellow named George Ordway, whose wife served on the board of the local Y.W.C.A., and frequently entertained guests at the house. In 1892, Ordway sold the house for $10,000 to the woman who would become the mansion’s namesake.

Lady McDonald was born in Canada in 1816, and in those days was known as Frances Mitchell, daughter of a London District Court judge, and niece of noted Canadian, Egerton Ryerson. In 1838, she married the unfortunately named Donald McDonald, who was actively involved in Canadian politics and served many years as a senator. McDonald was also a shrewd investor who amassed a fortune, mainly in real estate, and he, Frances, and their fourteen children lived at the center of Toronto society in a twenty-six room mansion. Mr. McDonald died in 1879, and Frances decided to relocate with a couple of children to Los Angeles. It is unclear if being the wife of a deceased Canadian senator whose assets include a Kansas cattle ranch is qualification for a title of nobility, but when the widow McDonald rolled into town, residents always referred to her as “Lady” with a capital L.

Lady McDonald resided at the mansion with various children, grandchildren, and servants for around twenty years and lived to be nearly 100. Following the departure of the McDonalds, the inevitable happened to house at 321, and it was divided up to accommodate multiple residents. Many tenants would come and go for the next five decades, including Frank J. Giradin, a landscape impressionist who not only lived in the mansion, but used it as his art studio and held a showing of his work at 321 South Bunker Hill in 1924.

Unlike many structures on Bunker Hill, which fell into stark disrepair as the years went by, this residence seems to have been well taken care of and was noted as being in “good” condition when a WPA census was taken in 1939. By the 1960s, the condition of the property was of little consequence because the neighborhood’s days were numbered. Before the decade was over, the residences of Bunker Hill were no more, including the former home of Lady Frances McDonald.

All photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Residence – 333 South Bunker Hill Avenue

Of all the dearly departed Bunker Hill mansions, the Castle and Salt Box are probably the best known. The two houses which resided at 325 & 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue were spared the wrecking ball, declared Historic Cultural Monuments, and posed for numerous photos before being moved to Heritage Square (and were subsequently burned to the ground by vandals). Rarely mentioned is the house that stood between its two more famous neighbors at 333 South Bunker Hill Avenue.

As discussed previously, the Castle, Salt Box, and 333 S. Bunker Hill were possibly all built in 1888 by Rueben M. Baker who lived in the Castle and either sold or leased the other two structures. The mansion had various occupants until it was purchased by Spencer Roan Thorpe in 1901.

Thorpe was a Kentucky native and descendent of Patrick Henry which gained him easy admission into the Sons of the Revolution and Colonial Wars. He served as a Confederate captain during the Civil War and was wounded three times before being captured by the Yanks and imprisoned on Johnson’s Island. Thorpe survived the War and made his fortune as a lawyer in Louisiana before making his way to Los Angeles in 1883. He purchased plots of land throughout the city, as well as a 150 acre walnut orchard in Ventura County. Thorpe also reportedly started the first settlement in what became the city of Gardena. He also served two terms on the Board of Police Commissioners of Los Angeles. When he moved into 333 South Bunker Hill Avenue, Thorpe was accompanied by his wife, Helena, and their five children.

Helena Thorpe hosted many social events at the Bunker Hill home, including a wedding breakfast for her daughter following early morning nuptials at St. Vibiana’s Cathedral in May 1905. Close friends and family would be reunited a mere four months later for Spencer Thorpe’s funeral.

On the morning of September 2, 1905, Thorpe left one of his ranch homes to travel out to Simi Valley and Moorpark. When his horse and carriage returned home alone, search parties were sent out and Thorpe’s body was found on the side of a road. There were no signs of foul play and it was presumed that he died of heart failure. His body was brought back to the Bunker Hill family residence and a small service was held at St. Vibiana’s. The surviving members of the Thorpe family lived in the Bunker Hill house for another year before selling it to an H.N. Green for $20,000 (a little under half a million in today’s dollars).

Like many of the homes on the Hill, the house was soon divided, and accommodated three households. By 1920, the mansion had been further divided into twelve residences, most of which were occupied by single boarders in single rooms. 333 South Bunker Hill Avenue saw some action in 1917 when Olive H. Faulk fell out of her second story window. Moments before her plunge, she had been cutting ham when her abusive husband, Irvin, pushed her into a corner and ordered her to pack her trunk and move. Apparently, he did not mean it, for when Olive tried to walk out the door, he locked and blocked it. Olive opted for the window, survived the fall, and filed for divorce. The L.A. Times astutely observed that the incident “ended their conjugal relations.”

The mansion at 333 South Bunker Hill Avenue survived into the 1960s with little incident. When the time came for the neighborhood to go, the houses on either side of 333 were selected to survive as monuments to a bygone era, and the mansion in the middle was slated for demolition. By 1967, the house at 333 South Bunker Hill was gone.

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection and the California State Library

Burning Bush on a Mount of Olives

When the residents of Bunker Hill discovered that the Alameda Street crib district prostitutes were living in their neighborhood, they drafted polite letters to the City Council and the Police Commission complaining about it.

When the residents of Bunker Hill discovered that the Alameda Street crib district prostitutes were living in their neighborhood, they drafted polite letters to the City Council and the Police Commission complaining about it.

But when they discovered that a rowdy religious sect called the Burning Bush had set up its headquarters on Olive Street, they called the police straightaway. Scarlet women were one thing, but cult leaders quite another.

Based out of Denver, leaders of the Burning Bush flock came to Los Angeles in the spring of 1904, and wasted no time in luring converts. In addition to their base of operations near Angel’s Flight at 315 Olive Street, they also established a revival tent at the corner of Spring and Seventh. At meetings, their followers would regularly shout, leap up and down, speak in tongues, and fall into semi-catatonic states for hours at a time. So enthusiastic were their cries that neighbors claimed they drowned out the sound of the streetcar as it rattled up the hill.

Based out of Denver, leaders of the Burning Bush flock came to Los Angeles in the spring of 1904, and wasted no time in luring converts. In addition to their base of operations near Angel’s Flight at 315 Olive Street, they also established a revival tent at the corner of Spring and Seventh. At meetings, their followers would regularly shout, leap up and down, speak in tongues, and fall into semi-catatonic states for hours at a time. So enthusiastic were their cries that neighbors claimed they drowned out the sound of the streetcar as it rattled up the hill.

Despite the leaping, members of the Burning Bush were not to be confused with the Holy Jumpers, another evangelical sect that had come to Los Angeles around the same time. Though they operated on a similar set of beliefs, the Burning Bush was generally considered to be less objectionable than the Holy Jumpers because they were not quite so loud. Additionally, while the Burning Bush had culled its leaders from respectable cities like Denver and Boston, the Holy Jumpers were from Alabama (gasp).

Despite the leaping, members of the Burning Bush were not to be confused with the Holy Jumpers, another evangelical sect that had come to Los Angeles around the same time. Though they operated on a similar set of beliefs, the Burning Bush was generally considered to be less objectionable than the Holy Jumpers because they were not quite so loud. Additionally, while the Burning Bush had culled its leaders from respectable cities like Denver and Boston, the Holy Jumpers were from Alabama (gasp).

While the Burning Bush’s evangelical fervor made them strange in the eyes of their neighbors, it didn’t make them a cult. What made them a cult was their practice of quickly separating initiates from all their money, real estate, and worldly possessions.

In 1906, a deaf man named Lorenzo Dunlap sued Burning Bush leader Charles Bryant to recover approximately $1000 worth of cash and property he’d signed over the cult with the agreement that they would hold the property in trust and care for him until he died. He’d feared that his own family members would try to have him committed to an asylum and swipe the estate for themselves.

But instead, the Bryants did. Dunlap claimed that once the money had changed hands, he found the Bryants cold and unwilling to support him. Additionally, they promptly sold Dunlap’s property in North Dakota at a tidy profit and used the money to buy themselves a fine Los Angeles area home and a cow.

It wasn’t just property they took. In 1905, a Mr. Vitagliano sent police to the Burning Bush house on Olive to find his 16-year-old daughter, Annie. Vitagliano said that the Burning Bush had torn his family apart, sending his wife off to Europe to do missionary work, turning his daughter against him, and constantly pestering him for money.

One of the saddest Burning Bush casualties was a Mrs. Elizabeth Northcutt, who was committed to the State Hospital for the Insane at Patton in 1908, after years tangled up with the Burning Bush and another group, the Pillar of Fire. Northcutt’s husband, a butcher, had exhausted all of his resources trying to nurse her back to health, even after she had emptied his bank account and abandoned him and their son for the Burning Bush, before finally returning home, frail and raving.

At her insanity hearing, Northcutt flew into a rage against his wife’s father, the wealthy James Murdoch, saying, "You ought to be ashamed of yourself for letting them send your only child to a public asylum when you are amply able to provide for her comfort."

Murdoch coldly replied, "She is your wife and it is your duty to support her. I have done much for her in the past. I have had financial losses and have large expenses of my own. I see no reason why the State should not care for her."

The examining physicians reported that "previous to ‘getting religion,’ Mrs. Northcutt was plump and merry. In two years, she has become a nervous wreck." However, they expected she would recover her senses in time.