1947project readers may remember this addition that King of Historians Larry Harnisch made to the blog back in its earliest incarnation. It‘s the story of Gerald Richards, and, because you can read the story in full in the link, I‘ll just toss out the particulars:

1947project readers may remember this addition that King of Historians Larry Harnisch made to the blog back in its earliest incarnation. It‘s the story of Gerald Richards, and, because you can read the story in full in the link, I‘ll just toss out the particulars:

Gerald Richards is 19, and he hasn‘t much in the world. He has a .25 auto that he picked up in Japan during his tour in the Maritime Service, and he‘s got George Kirtland, 24, who he picked up in New Orleans during his postwar wanderlust. It‘s 1947 and they‘ve landed in Los Angeles–George is from Gardena, Gerald an Illinois boy–and George goes to visit Gerald at his digs in the Biltmore. Gerald should have probably chosen somewhere less tony, because his argument over the $32 hotel bill resulted in his shooting the assistant manager in the lobby. Once nabbed, he also copped to two more slayings–a Tom Nitsch in New Mexico, and LA‘s own 52-year-old tailor Charles Vuykov, whose nude body was found on the floor of his room, 529 West Third.

In the 47p post, Larry made mention of the manner in which the Times heads off homosexual implications in Richards‘ Kirtland relationship; but then, what was 19-year-old Gerald doing in the apartment of a 50-something tailor? Especially a nude one?

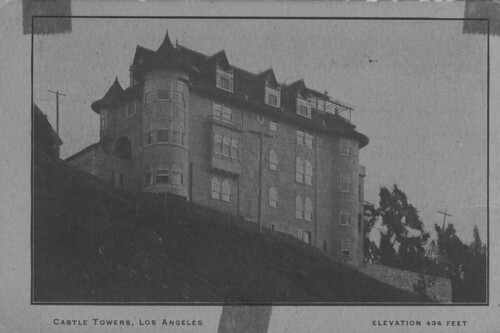

And let‘s not let this particular address of Vuykov‘s slip by”¦529 isn‘t just any spot on West Third. That shot reverberated across the four corners of Third and Grand. That‘s the Lovejoy Hotel.

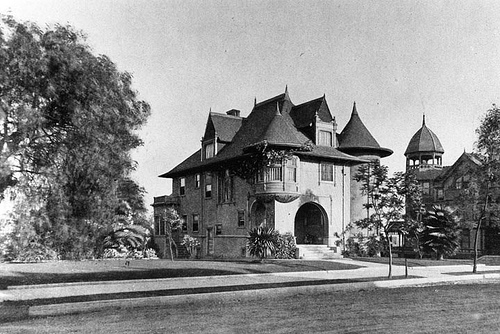

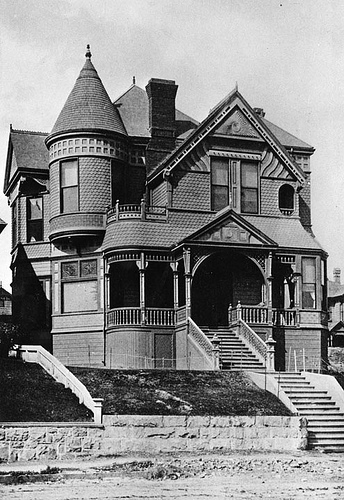

The Lovejoy is announced May 1903:

142 rooms, divided into 78 apartments, it opens in November.

It is immediately the scene of many a large society wedding, and home to the known (William O. Owen lived at the Lovejoy when it was finally decreed, in 1927, that it was in fact he who first reached the summit of the Grand Teton).

The Lovejoy is also a hotbed of lefty activity. It‘s a center for the Equal Rights League and magnet for suffragists of various stripe. It‘s where Professor Flinn‘s “physical culture” class met in 1904. It also serves as the 1930s home for the American League Against War and Fascism.

Above, looking north/east on Grand. (Nice crenellated parapets. Despite being against war, its residents were probably glad for defensible battlements.)

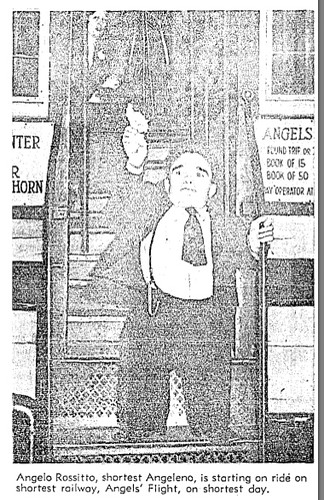

Now you see Angels Flight Drugs:

Now you don’t:

This being Third and Grand, the Lovejoy was also across the street from the Nugent. Below, the Nugent is on the left, and we peer down to Olive…there’s the top of Angels Flight, its neighbor the Elks Lodge, and the Edison/Metro Water Bldng at Third and Broadway in the distance.

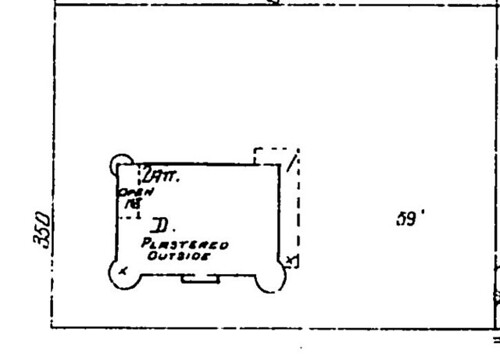

And, in our continuing effort to get you oriented, endless maps.

From the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, 1906:

From the Birdseye:

From the Baists Real Estate Atlas, 1926:

And of course, the WPA model from 1940:

Above, the Nugent has lost the top of its tower. And is also apparently falling over.

The Lovejoy stands strong, though painted yellow, as per its reputation for hosting pacifists.

The 1960s saw its demolition, and in its place, in the early 80s, the erection of a similarly formidable fortress, Isozaki’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Through true to the Hill, it’s styled less like a castle than it is bunker-like.

Lovejoy images, from top to bottom: author; William Reagh Collection, California History Section, California State Library; Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library; William Reagh, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; William Reagh, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection