On November 5, 1898, Private George W. Swing, Company K, Seventh Regiment, United States Volunteers, sent an unusual request to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. Identifying himself as representing a committee of the Seventh Regiment, he requested the Chamber organize a regimental public drill later that month in Agricultural Park, now called Exposition Park, for the purpose of raising money for a monument dedicated “to the memory of the dead soldiers of the Seventh” who were serving during the recently concluded Spanish-American War.

Private Swing also wrote a letter to the Los Angeles City Park Commissioners, possibly on the same day he wrote to the Chamber. In his letter to the Park Commissioners, Swing stated that the Seventh Regiment requested their co-operation in placing “in one of the city Parks a monument in memory of their comrades who died during service in the late war at a cost of about $3,000…”

These two letters set in motion a process that created the city”™s first public monument and bequeathed to the city its oldest public art.

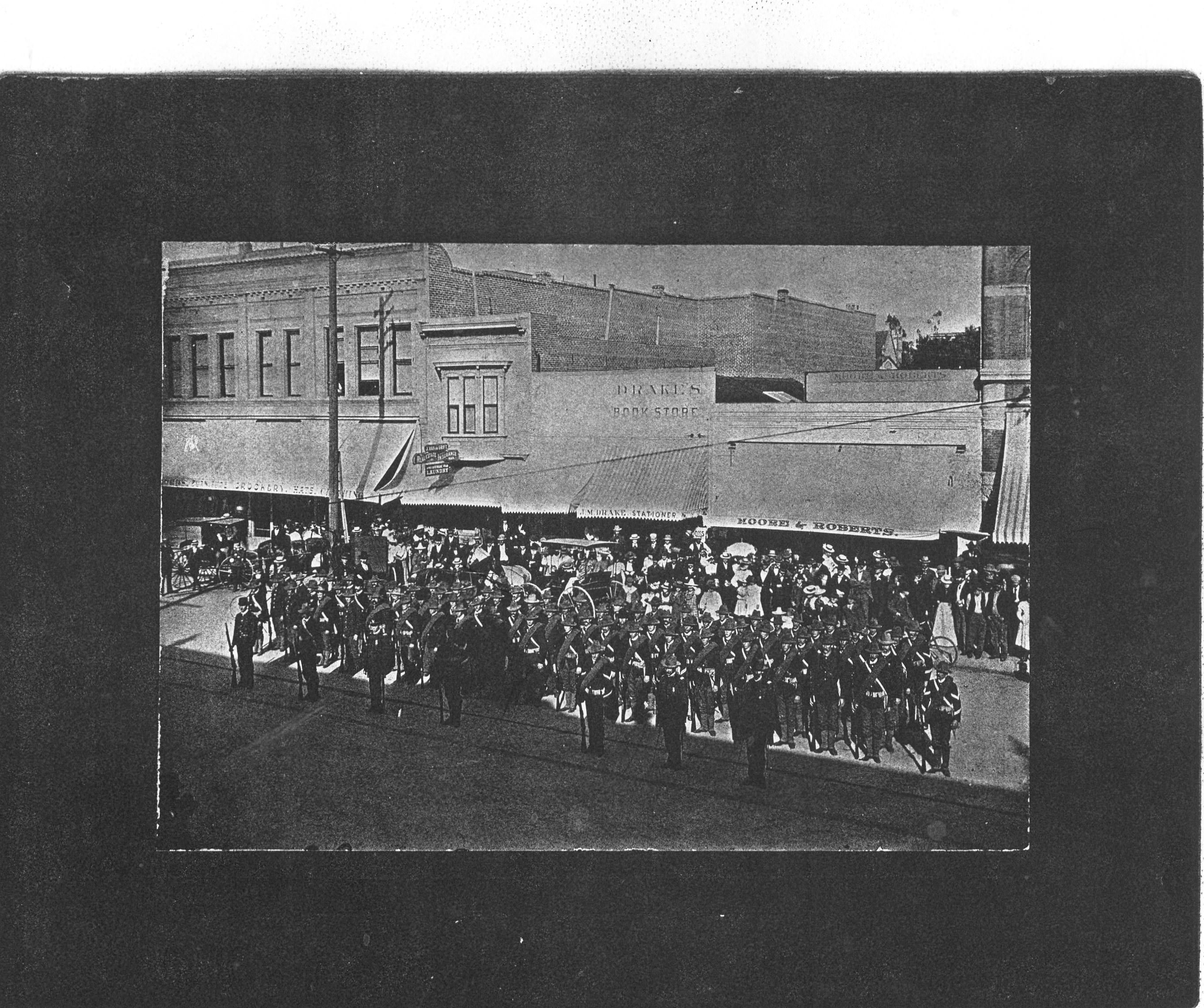

It was not surprising that members of the 7th Regiment wanted a public expression of remembrance of their fallen comrades. The Regiment had been in the public eye from the day it marched off to war on May 6, 1898. That long hot day beginning before dawn for the Regiment”™s 900 young men was unlike any they had ever experienced before. When it was over, they had experienced a day filled with symbolism serving as a rite of passage that transformed them from civilians into soldiers to fight a war with Spain.

Rising before dawn, Harry E. Goodrich, a 29 year old farm laborer made sure he was at the Riverside armory by 5:30 to join the other 83 men in his unit, Company M of the 7th Regiment. But as he walked to the armory, he discovered that other people in Riverside had also risen early that morning. The streets, according to the Riverside Daily Press “were alive with people”. Goodrich remained at the armory for a short time. Within a half hour of assembling, Company M began their march to the Southern Pacific station where a train was waiting to take them to Los Angeles. Their journey through the streets of Redlands was a communal effort. A squad of policemen, embodying law and order, led the parade, followed by aging members of the Grand Army of the Republic, serving as patriotic models and symbols of self-sacrifice and courage. The Knights of Pythias and the Knights of the Maccabees, two of Riverside”™s fraternal organizations, were next in line serving as symbols of volunteer and community service. Behind them were the men who volunteered to serve in the war against Spain but were rejected for physical reasons. And bringing up the rear of the parade were the men of Company M. While marching to the station, the Riverside Concert Band joined them, providing musical support and a military cadence to the steps while “a mass of humanity” lined the route, cheering as they all passed by. After arriving at the train station, the men bid their last farewells to friends and loved ones, and as they boarded the train, the band gave a patriotic air to the occasion. When the train left the station and headed west, the band gave a final theatrical touch to the departure by playing “America” as the men waved farewell from the windows and the rear platform drawing a “last farewell cheer from the throats of the mass of people, assembled at the depot”.

The train proceeded to Riverside where it picked up Lindsey G. Wood, William Marske and the other 87 men of Company G from Redlands. Awakened at 4:30 by church bells, the men assembled at the armory. Their parade to the Southern Pacific station three blocks away was not as elaborate as the one in nearby Riverside. Marching over a foot deep carpet of flowers laid out along the route, they were accompanied only by members of the Grand Army of the Republic. But this mix of raw untested volunteers and aging veterans passed under banners stretched across Orange Street that evoked godly intervention with “God bless you boys” and stirred the troops, not with idealism, but with revenge by telling them to “Remember the Maine”.

Leaving Redlands, the train proceeded to San Bernardino, where 27 year old George Swing was awakened at 5:00 a.m. by a chorus of church, school and fire bells. Stirred by the wake-up call, he dressed and walked to the San Bernardino Armory where he joined Curtis Rollins, William H. Dubbs, and the other men of Company K. People as far as 10 miles away were also awake and came to the armory to say farewell, and leave flowers, flags, boxes of oranges and other objects to show their support. With all the men present, at 6:15, the unit left the armory and marched to the train station, passing an honor guard of various fraternal organizations, including the Women”™s Relief Corps, and the Confederate and G.A.R. veterans. Patriotic music filled the air as the Cadet Band led the men to the station. A large crowd of men representing “every walk of life”–merchants, preachers, lawyers and judges, bankers, and farmers were joined at the station by an equal number of women and children to say their tearful farewells.

After picking up Company K, the train continued to Pomona, where Herman L. Hils and the other men of Company D had gathered. Company D”™s departure was a strikingly simple affair. Instead of a parade from the armory, the men assembled at the station, said farewell to family and friends, boarded the train with its two coaches decorated with flowers by the Fruit and Flower Mission “girls”, and left for the final leg of the journey to Los Angeles.