Nice addition to the Daily Mirror, without which this city would be much poorer indeed.

Hey, note the double use of the Foss/Heindel.

A Lost Neighborhood Found

Nice addition to the Daily Mirror, without which this city would be much poorer indeed.

Hey, note the double use of the Foss/Heindel.

It’s not an Edwardian octoplex full of grime and grifters. It‘s not even on Bunker Hill. But we‘re going to tell the tale of the Architects‘ Building, and if not to you, faithful OBHer, then to whom?

All and sundry weep for the Richfield. It‘s not altogether true that everyone turned a blind eye during its”68-9 demo. Even the Government knew enough to come on out with its Instamatic and take lots of snaps.

The November 1968 Times article “Black and Gold Landmark: End Arrives for LA‘s Richfield Building” discusses those architecture students who believed the structure a remarkable example of “Jazz Moderne” worthy of preservation.

And the only mention of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth (which by 1968 had been renamed the Douglas Oil building) and which shared the block with the Richfield was as such:

”¦and that was the end of that. According to Cleveland Wrecking‘s general manager, the million-dollar site clearance project, of the block bordered by Fifth, Flower, Sixth, and Figueroa, was the largest ever undertaken in the West.

What is this Architects‘ Building of which we speak? Who architected this interbellum edifice?

Downtown is very nearly defined by Parkinson, and you can‘t mention LA without Morgan, Walls & Clements (Stiles sitting in the softest spot of this writer‘s heart), and if I mention Walker and Eisen, you‘ll say Yaaay! and I‘ll agree, and we‘ll high-five, and then get cut off and kicked out of wherever we are. It sure is swell to take those Conservancy tours and see all these places, but when the Conservancy cats go back to their digs, they return to a Dodd and Richards.

And you say, who?

William J. Dodd, student of Jenney and Beman is one of the great Midwestern architects. He came to California and is credited–though scholars still dispute to what extent–with a portion of Julia Morgan‘s 1914-15 Examiner Building. This he did with his partner at the time J. Martyn Haenke. In 1916 he partners with engineer William Richards. They produced so many an important Los Angeles structure that I will at some point in the near future add their full history as a comment appendage to this text, to keep from having too many appetizers before our twelve-story entrée.

We’re talking about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa, not to be confused with our friend on the kitty-corner to the northwest, the Monarch Hotel.

The first rumblings about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa come in February 1926, when mention is made of preliminary plans and lease negotionations for a million-dollar skyscraper to house LA‘s building trade. Sponsoring the project are Morgan, Walls and Clements, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, Webber, Staunton and Spaulgin, Carlton Monroe Winslow, Elmer Gray and McNeal Swasey.

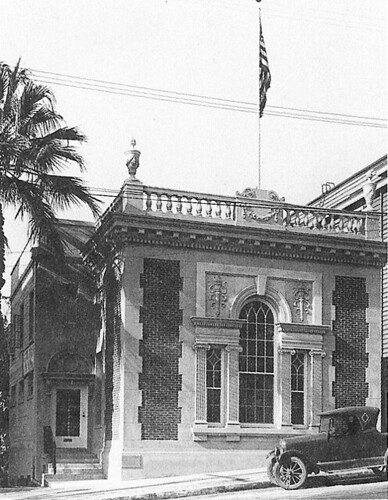

The big announcement is made in February 1927 about the $650,000 height-limit to be built on the southeast corner of the Fifth and Figueroa. To be known as the Architect‘s Building, after New York and Chicago, it would be the third of its nature in America: a whole structure exclusively devoted to the various branches of the construction industries. It is to be of a “modified Italian” architectural treatment according to the associated architects drawing up the specifications: Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carleton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson.

Twelve stories high, with a site of 60 by 156 feet, it is to be of steel reinforced concrete, 143 offices, its exterior finished in plaster with cast-stone trimmings. Its seven upper floors of the building are to be leased to prominent architects, its first floor and mezzanine to be occupied by the Metropolitan Exhibit of Building Materials–a massive exhibit of every branch of the building industry, renamed the Architects‘ Building Materials Exhibit.

By November of 1927, the building was nearing completion. Preston S. Wright, president of Wright-Aiken, owners of the AB, ran down some of the tenants: Rapid Blueprint Company; D. C. Writhg, insurance; E. E. Holmes, insurance; William Simpson Construction Company, builders; Brian D. Seaver, attorney; and architects D & R, Coate, Johnson, Winslow, and William Lee Wollett.

816 opens in January, 1928. It came in at $662,000.

The depression would not be good to the Architects‘. It was foreclosed on its $360,000 outstanding bonds in February 1933. It was put under federal receivership and forced into a court-ordered sale, which didn‘t occur until May of 1938, when an F. V. Fallgren and associate could pony up the 300k to a trustee representing the bondholder‘s committee.

The Architects‘ Building survives just fine through the 40s and 50s.

One bit of drama: Evans Erskine, 34, a jobless Air Corps vet, figured that 1955 would be Year Last. He climbed to the ninth-floor fire escape of the Architects‘ Building and hoisted himself over the railing. Richard McGowan, a controller for Dames & Moore Civil Engineers, ran down the hall and and grabbed the hands of the nattily dressed, ledge-teetering Erskine poised 100 feet above Fifth Street. Here, McGowan reenacts his daring hand-grabbing:

In 1959 it is purchased by Douglas Oil, a southern California independent who run three refineries and 300-some gas stations in the Southland. It remains the Douglas Oil building despite Douglas‘ purchase by Continental Oil (AKA Conoco) in 1961.

It‘s the 1960s when the folk in 816, heck, the building itself, could hear the dirge of doom wafting on the wind. Listen, it‘s coming from over by the Richfield building.

Richfield, another oil company, who owned that big ol‘ black and gold tower to the south, had merged with east coasters Atlantic Refining in 1966. Richfield had already begun buying up the block for piecemeal parking, and as Atlantic-Richfield Co. they purchased the whole kit. And kaboodle. That called for the end of the Architects‘, as ARCO intended to build not one but two Miesian towers (though their New York twin-tower counterparts broke ground four years earlier, there appears to be an aesthetic epoch between AC Martin’s work and Yamasaki’s tube-frame twins of lower Manhattan, whose postmodern sensibility stems from a neo-Gothic use of aluminum).

1967, and all‘s well:

1969, during the demolition. The Architects‘ Building, now one-fifth off! The Richfield, now with two-thirds less Richfield!

1970, towers going in.

Left to right, the Tishman Building (Victor Gruen, 1960, though you know it like this), Glore Forgan Staats, the Gates Hotel (now a fine Brooks Bros), St. Paul‘s Cathedral (razed), the Hilton (note how it changed from the Statler to the Hilton between 67 and 69), the Jonathan Club , the Carlton Hotel (razed), Caldwell Banker.

Below, today. Note the wee bit of the Jonathan peeking out.

The ARCO Towers still stand in all their glory. For now.

Another shot of the demolition. The Sunkist, Engstrum and Edison line Fifth. The Telephone Tower on Grand. In the distance, left, Bunker Hill Towers going up.

A mid-60s aerial. Central Library bottom right. The Sunkist at Fifth and Hope. Halfway up Hope behind the Sunkist, the tiny Sons of the Revolution and the Santa Barbara. The big apartment building at the southwest corner of Fourth and Hope was the Barbara Worth.

Of course we’re not getting away without the requisite model and Sanborn additions:

Note how Fourth Street ends at Flower. Compare to the 60s aerials which indicate the magnitude of the 1954 Fourth Street Cut.

Just to clear up one bit of confusion. Despite early mention that this building was to be of the combined effort of Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carlton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson”¦it‘s a Dodd and Richards. Even Adrian Wilson, who in April 1967 wisecracked “I hope our new location won‘t be so temporary” in an article about his having to move out of the AB after thirty-nine years, remarks that Dodd and Richards designed the building–and he should know, the plans for 816 are inscribed with his own initials, as he was their draftsman before he hung out his own shingle when the building opened in 1928.

Clockwise from the south: Sixth, Figueroa, Fifth, Flower:

That then is the tale of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth. Remember the diaspora the next time you‘re in the neighborhood.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library photo archive, University of Southern California, and Arnold Hylen and William Reagh Collections, California History Section, California State Library

After the DWP and Dorothy Chandler went up, postcard photographers said whoopee! something to shoot besides City Hall and the Chinese. So they cruised up to the bluff on Huntley, trained their lenses across Second and Beaudry toward First and Flower and fired away. The day view is a Plastichrome by Colourpicture, the night view by Western Publishing & Novelty, both circa 1965.

Dig the Union station in all its 76 ball glory (the SoCal station with its backlit chevron seems to be of an earlier vintage; they‘re both gone now). Printers shops and giant spools line Beaudry. Were it not for the necessity of capturing Becket and Martin‘s latest accomplishments, would we have any record of these? Not likely.

Across the Pasadena Freeway, on Bunker Hill proper, on the west side of Figueroa between First and Second, that big white structure? That‘s 123 South Figueroa, built in 1925. Whatever the most photographed buildings on Bunker Hill were–the Castle, the Brousseau, the Dome?–if there‘s another image of this structure, I‘d love to see it.

123 was erected as an office building, but in 1934 is turned into “one of the largest and most modern” government relief centers in the West. The Federal Transient Service converted the building into its Southern California headquarters, i.e., a shelter for non-resident jobless men, outfitting it with an enormous cafeteria and dormitories that slept 500. It became a veritable city in itself: showers, lockers, hospital, educational and recreational facilities were installed, as were a laundry, shoe repair and tailor shop. It was also a warehouse for materials and supplies used in the camps. Yes, the camps. Itinerant men had forty-eight hours to stay at Figueroa, max, before being assigned out of the city to transient work camps in forest and mountain areas.

Families, bands of “wild boys,” vagabonds on freight cars”¦in 1935 32,000 new transients came to California each month, 12,000 of those to Los Angeles. July of 1935 alone saw a load of 20,000 paupers arrive in LA seeking State and Federal aid. (And, one supposes, oranges that grew on palm trees.) 1,200 boys were sent to forestry camps, 4,000 men to the Federal aid camp near San Diego, but many of LA‘s transients–12% of the national and 60% of the State‘s burden–after being processed here at 123 South Fig, ended up in squatter‘s villages and squalid encampments. Many went to homes and camps, were absorbed to into County Welfare healthily, found employ in the works relief programs or went back from whence they came, but either way, it does show and say something about the class shift of the Hill that such a major locus of poverty and despair should be located within its confines.

123 is converted to the police department‘s traffic division headquarters building in 1942. The City Council gave the Police Commission $78,000 for the building and another $47,000 for the alterations.

At the dedication, during a luncheon given on the third floor, attended by Mayor Bowron, Chief of Police Horral, and numerous high ranking police officers, Deputy Police Chief Caldwell announced that Los Angeles led the nation in the decrease in auto fatalities–which occurred through “strict, scientific enforcement of driving regulations.” (Reports from 123 show that pedestrian fatalities in the first half of the 40s skyrocketed–dimouts for the war effort, don‘t ya know.)

At the dedication, during a luncheon given on the third floor, attended by Mayor Bowron, Chief of Police Horral, and numerous high ranking police officers, Deputy Police Chief Caldwell announced that Los Angeles led the nation in the decrease in auto fatalities–which occurred through “strict, scientific enforcement of driving regulations.” (Reports from 123 show that pedestrian fatalities in the first half of the 40s skyrocketed–dimouts for the war effort, don‘t ya know.)

The biggest piece of drama attached to the building came when in 1950 Parry Cottam, 27, a maintenance man at the police garage in the building, was moving a police motorcycle and it went out of control. It plunged him through a large plate-glass window on the building‘s street level, and he was found unconscious on the sidewalk.

In March of 1964, the Board of Supervisors authorized sale of the county building to the CRA. The CRA said they intended to develop the site into a motel. The garage equipment goes up for auction in April 1971 and the 123 is presumably demolished failry soon thereafterward. While the CRA didn‘t build a motel after clearing the site, the Promenade Towers have at least been described as a “roach motel.”

It‘s a $60million dollar complex, the first mixed-use apartment complex in downtown Los Angeles and the area‘s first privately owned residential rental complex. It has its formal opening June 16, 1986, the name Promenade intending to connote the era of pedestrian-oriented urbanism this project will usher in.

The Promenade becomes a favorite of Union Bank; they keep sixteen apartments there for visiting businessmen. Tommy Lasorda himself keeps a pad in the Prom. They‘re all drawn by the health club and gymnasium, market, pharmacy, dentist, café/restaurant, the 24-hour reception and valet and garage attendants and so forth.

It remains to be seen whether the 123 regains its Reagan-era splendor, or if its residents, with their dry cleaner and little shop of sundries, doesn‘t harken back to its forgotten days as a haven for homeless men and law enforcement.

People land on cars. They just do. It‘s how Daredevil and Crank end; it‘s how Lethal Weapon begins. Pauly lands on a car in Darkman; Conan O‘Brien lands on a car in South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut. And then there‘s George Costanza‘s suit against the hospital whose mental patient landed on his automobile. Clinicians call it the Evelyn McHale Syndrome, or at least I do.

In December of 1941, Mrs. Charlotte Neill, 70, called the gas company to turn on service at 2536 Reservoir Street. The Gas Co. sent out Perry C. Butler, 48, who attacked her, causing shock and other injuries necessitating her hospitalization.

Arrested the 26th, arraigned the 29th and free on bail, Butler was five days later, for some reason, atop the Subway Terminal Building. But not for long. It‘s unclear as to whether he fell or jumped the ten floors and crashed to the top of a car on the roof of Savoy Garage.

Assuming Butler jumped, it makes one consider that the auto is the modern equivalent of the sword, which Saul so famously fell upon after battling the Philistines. But consider: Detective Lieutenant B. G. Anderson was lead investigator in the apparent suicide attempt. Because Anderson was also, by coincidence, arresting officer in Charlotte Neill‘s attack case, it makes one wonder if this particular car-landing didn‘t have an element of the Ness/Nitti to it.

Above, the Subway Termial Bldg at right, adjoining the low-slung Savoy Garage onto which Butler made his car-smashing plunge.

In what will surely go down as the smarmiest piece of journalism in history, the Times recounts the travails of Toy Lane, dancer at the Chinese Junk, 733 North Main. She made her way over to the Junk from her pad at The Ems to shimmy for shekels on September 25, 1946. When she gets into the nightclub dressing room to “dress” for her act (the Times‘s flippant application of quotation marks, not mine) she discovers her wardrobe has been stolen: G-string No. 1 (black and orange, beaded,) $35; G-string No. 2 (silver metallic cloth,) $23; beaded shaker, $20; rhinestone brassiere $20; an anklet and armband set, $25.

Miss Lane, it was reported, was mortified–she had to dance with her clothes on!

In a final piece of facetiousness, the Times noted “the police were searching for the burglars and the large van they must have used to carry away the loot.”

The Chinese Junk Café:

Which was up in China City, a 1935 Chinesque development that predated New Chinatown, and had been the baby of wealthy socialite and “Mother of Olvera Street” Christine Sterling. China City was mostly burned out, literally and figuratively, by the early 50s.

And of Ms. Toy‘s home, the Ems?

Remember the Palace/Casa Alta post, which was long on storytelling but short on pretty pictures? I even chided you for looking at a structure that was not our hotel-in-question, by tossing über-comely Bunker Hill lass The Ems smack dab into the mix.

I even promised I‘d talk about the Ems “next week,” but by next week it was President‘s Day, and somebody had to make you mindful of your nation, despite all the patriotic work you were doing watching Obama informercials.

Well, now it‘s the week after next, and it‘s time for the Ems, which is replete with pretty pictures but sadly short on storytelling. Here‘s what we know.

Charles Clayton Emswiler came to LA in the boom eighties and went into the apartment-house building game. In August of 1905 he pulled permits to build his eponymous Mission-style Ems, designed by none other than Joesph Cather Newsom. Emswiler died in 1922, age 69, in the apartment house at 321 that bore his name.

It contains 110 rooms, divided into twenty-six apartments according to the 1939 census, sixty-five apartments according to the 1950 Sanborn map. Here it is before its birth, from the 1896 Sanborn map (321, bottom), and postnatal from the 1906:

Our earliest known shot, above. Pre-1908, because the Kellogg has yet to be built to the north. Notice the three round-arch traceried windows along the street, and the turreted house to the south.

We know that it had a large ballroom, for in 1909 the papers announced that sixty couples participated in the dancing at the inaugural ball honoring President Taft.

The Ems were apartments-of-choice for a collection of colorful characters.

1914. “Mohawk Half-Breed” Daniel T. La Rae, alias Daniel T. Ray, was an Ems resident (Emsident?) with Miss Emma Ewalt–they stayed there together, but were (!) unmarried. Daniel spent a lot of time promising to marry Miss Ewalt, even going so far as to travel to Shelby, Ohio, to visit her father. Mostly what Daniel did, though, is borrow money–he needed these sums to purchase marble on bond to build post offices and such. Of course he could be trusted; he was a Federal Officer, after all.

He had shown Emma a badge emblazoned “U. S. Marshal,” but never paid back the money nor made good on his promise of marriage. Of course his badge was a phony as his promises. Turns out his real job was for the Southern Pacific RR, guarding Chinese as they were ferried from San Francisco across the Mexican border line. Chinese actually go home to Mexico. Little known fact.

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse, 1840 Lebanon. The liquor was valued at $40,000. In addition to the liquor, the drys seized a large truck, three touring cars and several rifles.

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse, 1840 Lebanon. The liquor was valued at $40,000. In addition to the liquor, the drys seized a large truck, three touring cars and several rifles.

Above, the Ems in 1912 and a William Reagh image ca. 1960. Notice the rounded tripartite fenestration, which worked so well with the rest of the façade, has been changed to a single remaining arched window, a square window, and a doorway. This is due to owner William Fisher’s February 1927 alteration–he hires architect B. N. Rickard, of whom you have never heard, and rightfully so, since this is pretty clunky work, to convert the lobby into two bedrooms and turn the ball room into a new lobby. (Note too that the neighboring house–built in 1887-88 by Howard W. Mills, of real estate firm Mills, Crawford, Pauly & Clapp–at 327 South Olive has been reduced to a concrete pit, demolished for a parking lot in the summer of 1948. )

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to 903 West Twenty-First St. to fill a position as a mother‘s helper. As soon as she got the job, she was attacked by mother‘s son James D. Anderson. Erma wasn‘t the first to have met with the fate of an Anderson Employee–one Marguerite Cooper, 23, also testified with Erma in Municipal Court about a similar sitch, and the Judge ordered Anderson held on $10,000 bail.

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to 903 West Twenty-First St. to fill a position as a mother‘s helper. As soon as she got the job, she was attacked by mother‘s son James D. Anderson. Erma wasn‘t the first to have met with the fate of an Anderson Employee–one Marguerite Cooper, 23, also testified with Erma in Municipal Court about a similar sitch, and the Judge ordered Anderson held on $10,000 bail.

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at 30th and Broadway, when he fatally struck Mrs. Marianna Valenzuela, 58. Hey, I warned you that the Ems lacked gripping and protracted tales. But look at those pretty pictures.

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at 30th and Broadway, when he fatally struck Mrs. Marianna Valenzuela, 58. Hey, I warned you that the Ems lacked gripping and protracted tales. But look at those pretty pictures.

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the Belmont had two in ‘42). It‘s easy to posit that the suicide rate is a constant, and the papers make a point of reporting ”˜em during wartime to detract the populace from all those incoming body bags. If you go for that sort of mass-media-control conspiracy. That notwithstanding, nine months after we got into the war, Joseph Buotha, a 58-year-old former private investigator, ate several bottles of pills in his Ems apartment. He had just written a long telegram to Eleanor Roosevelt, and this note: “Please let me alone. Let fate take its course. Notify John G. Wenk to take care of my belongings. Please don‘t hurt the dog. May God forgive you.”

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the Belmont had two in ‘42). It‘s easy to posit that the suicide rate is a constant, and the papers make a point of reporting ”˜em during wartime to detract the populace from all those incoming body bags. If you go for that sort of mass-media-control conspiracy. That notwithstanding, nine months after we got into the war, Joseph Buotha, a 58-year-old former private investigator, ate several bottles of pills in his Ems apartment. He had just written a long telegram to Eleanor Roosevelt, and this note: “Please let me alone. Let fate take its course. Notify John G. Wenk to take care of my belongings. Please don‘t hurt the dog. May God forgive you.”

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

There‘s that railing! The railing of DEATH!

Ok, the railing of death. It‘s not much, but it‘s something.

Of course we know how the story ends. The Ems gets its demo permit pulled in July 1965. By the summer of ’66 it’s just a pile where a truck can pull up, while erstwhile neighbor the Casa Alta is undergoing a similar fate:

After the last few posts–piles of brick, crenellated castles, Neo-Classical noodling–I am happy to say look at all that stucco (stucco that‘s supposed to be there, not stucco that was thrown over shingle–although to be honest, it wasn‘t thrown over adobe brick, either). The deep arcades, the rounded arches, the low-pitched red tile roofs”¦Mission Revival sure oozes picturesque. Were the square flat roof to call a California antecedent to mind, you might think of the 1894 Burlingame train station.  The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish St. Regis.

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish St. Regis.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

When it comes to architecture important to this part of the world, it can be argued that Spanish Colonial/Mission Revival is our own honest, expressive flowering, that‘s crowd-pleasing but not childish, sometimes silly but never stupid, hard to notice sometimes and often hard to preserve.

It‘s sad to lose Bunker Hill in general; we’re sorry to lose the Ems in particular.

Early shots, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; later b/w shots, William Reagh and Arnold Hylen Collections, California History Section, California State Library; color shots, Walker Evans, “439 Architectural Views for Time-Life Project ‘Doomed Architecture'”, metmuseum.org

This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

The Sons of the Revolution–open to those with a lineal descent from those who fought for the Patriot cause (not as hard to get into as the Society of Cincinnati, but harder to get into than the Sons of the American Revolution, which wasn‘t founded til thirteen years after the Sons of the Revolution, for reasons I won‘t get into here)–seeks to forever keep alive the first men to fight for our treasured traditions. And perhaps because YOU had some great great somebody at Cowan‘s Ford, they keep a genealogical library so that you may do the necessary research into possible membership. Today, their 110-year-old collection has 30,000+ volumes kept open to the public, free of charge, in Glendale; but the road there has been bumpy, save for forty years of comparative calm on the Hill.

The Sons of the Revolution of California was founded in 1893, and by the turn of the century had some 5,000 volumes regarding the Revolution and Colonial America, especially in relation to the West. Its first establishment was in the offices of the Society‘s first President, Col. Holdridge Ozro Collins.  Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Bonebrake-Bryson Block (Joseph Cather Newsom, 1888), NW corner of Second and Spring, shown here before and after its remodel. It was further remodeled into an open pit, as its corner site is now where the 1948 Times Mirror Building stands.

The Society stayed in the Bryson Block from May of 1893 until June of 1894, when Collins moved his offices, and the library, into the brand-spanking-new Stimson Block (Carroll H. Brown, 1893), NE corner of Spring and Third.

The Stimson Block was the first six-story building in Los Angeles, the first steel frame building in Los Angeles, and the last major example of commercial Richardsonian Romanesque in Los Angeles when it was unceremoniously demolished for a parking lot in July of 1963. (We do have a good extant Victorian Richardsonian house”¦and it‘s also Stimson‘s.)

In any event, Collins and the library stayed at Stimson Block until it was decided that it was time for Col. Collins to get his room back, and for the library to have a place of its own.

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

But the Society kept growing, and a decade later–January, 1908–they were moving boxes into the San Fernando Building (John F. Blee, 1906), SE corner Fourth and Main.

They started knocking out walls on the sixth floor until additional stories were added in 1912 and the Society moved into quarters specifically designed for the library. By 1914, they outgrew even that and had to take on an additional room. Making matters worse (good for the library, bad for space concerns) was that Orra Eugene Monette, aka Mr. Bank of America, Society President, (Mayflower, Colonial Wars, Huguenot Society, ad infinitum) gave a large collection to the library.

Again showing their preference for new buildings, the Society turned their eye to the new Citizen‘s National Bank Building (Parkinson & Bergstorm, 1914) at the NE corner of Fifth and Spring; the building is still there, but has mysteriously been stripped of its architectural embellishments.

And there they stayed until Nathan Wilson Stowell donated to the Society a plot of land on Bunker Hill.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

When Stowell died in 1943, he was the last of the 20 charter members of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. (And although his forebear who came to Massachusettes in 1620 was named Samuel, and the rest of his mishpucha are variously named Abraham, Isaac and Israel, Nathan maintains he is a Protestant.) Despite his importance to the history of Los Angeles, or perhaps because of it, some cultural terrorist elected not to restore his name to the Stowell, which was renamed the Earle in 1950 after its acquisition by the Milner chain, and redubbed the El Dorado in 1955.

So Stowell donates the land to the Society and made a point of submitting his own plans for the building, to cost $25,000. In October 1927, they held a ceremonial groundbreaking to turn the first shovelful of earth:

Left to right: Lansing Sayre; Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens, Bishop of Los Angeles; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., California Society of Colonial Wars. 1926-27); Philip E. P. Brine; Dr. Daniel L. Ransom; James D. Hurd; Dr. Edward M. Pallette, President; Wilson Milnor Dixon, Librarian (holding shovel); Charles B. Messenger; Orra Eugene Monnette (waving hat); Charles F. Bouldin; Dr. Egerton Crispin; unknown; Cassius Milton Jay, Secretary; Col. Harcourt Hervey, Marshal; Edward Bouton, Jr.; Dr. James D. Eaton.

Left to right: Charles F. Bouldin; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., Colonial Wars); Edward M. Pallette, President, shaking the hand of Willis Milnor Dixon, Librarian; Lansing Sayre; John Emerson Marble; Orra Eugene Monnette (holding hat); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Cassius Milton Jay; Burnham Robert Creer (partially hidden); Edward Bouton, Jr.; unknown; Dr. James Demarest Eaton; and Dr. Daniel L. Ransom.

Left to right: Mrs. Frank Pettingell; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (U.S. District Judge; future Society President and General President Sons of the Revolution); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Bishop William Bertrand Stevens and Dr. Edward Marshall Pallette.

Above, on November 26, 1927, Dr. Pallete officiated at and Bishop Stevens conducted the services at the laying of the cornerstone. Within the cornerstone were deposited historic documents from the Sons and Society of Colonial Wars, along with 7th century Arabic manuscripts; a Spanish silver seal from the time of Ferdinand and Isabella; a California pioneer gold dollar of 1854, and a pass through the Continental lines issued in 1871 by the Supreme Executive Council of the Pennsylvania Colony.

The library opened to the public February 1, 1928.

They burned the mortgage in 1935:

Left to right: unknown; Lansing Sayre; unknown; Nathan Wilson Stowell; Willis Milnor Dixon; Orra Monnette; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (General Registrar, General Vice President, 1934, General President, SR, 1937); W. W. Beckett; James Black Gist; E. Palmer Tucker, President (sitting); Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens (Episcopal Bishop of Los Angeles, General Chaplain, General Society of the SR, 1940-1947); Dr. Edward M. Pallette; Egerton Crispin; unknown; and Cassius Milton Jay (Treasurer).

Now then, of the building.

Let‘s talk Stowell‘s style. In the last ten months of OBH you‘ve seen a lot of structures, but nothing quite like this handsome dentil‘d and bequoin‘d Georgian. The Federal-style flat roof behind the balustrade, and that Palladian window”¦what does that remind you of? Come on”¦

Of course”¦what could be more appropriate than appropriating from Independence Hall?

Inside, what more could one ask for?

The secretaire with broken pediment, the Ionic capitals, the Doric pilasters, the plaster medallion, the comforting keystone? One can gain an almost perfect serenity from gazing into this image (imagining the hypnotic tick-tock of an Elias Ingraham on the mantel…kept me in ataraxia all these feverish months, allowing me to postpone this post to President‘s Day).

Another corner of quietude and sobriety:

The library opened its doors to other patriotic and hereditary societies, e.g. the Society of Colonial Wars, Order of Founders and Patriots, and the Mayflower Society; of course the DAR hosted more than a few luncheon n‘ lectures.

While the library naturally abjured the wild Bunker bacchanal, perhaps we should make mention that it did have some interesting neighbors (okay, so this post doesn‘t get away totally scot-free when it comes to tales of queer criminality).

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

437, between the Touraine and the Santa Barbara, before the 1927-8 Society building (Sanborn Map, 1906) and after (Sanborn, 1950):

Tales of the Tourained.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Mrs. Helen Roberts, Miss Eva Knoll, and Mrs. M. Brader, of the Santa Barbara Apartments, were three of the ladies who fell under his sway. They probably found him less dashing as they stood in court and identified various articles of jewelry, looted from their rooms in the Santa Barbara, found in de Marquette‘s possession.

He also made the rounds as none other than Donald Crisp, and supported himself by writing ficticious checks as the actor/director.

Turns out that he‘s just Leonell Gianini, a repeated youthful offender who‘d been sent to Whittier for burglary. His folks are ranch owners with a farm out in Ocean Park Heights (renamed Mar Vista in 1924). Nevertheless, in court, he claimed the jewelry as heirlooms “from his ancient and honorable family” in France. He got five years at Folsom.

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

At his trial, Pfeiffer denied contemplating a bank robbery. “I am a somnabulist,” he explained. “On the morning in particular, I walked in my sleep and went over to the table to write this note, which was found by the detectives when they called several hours later. It was all a dream. I dreamed that I had held up a bank.” Deputy City Prosecutor Ford Q. Jack, reminding the court that in several recent hold-ups the same method had been employed, asked that to curb the dream alibi in prospective bank robbers, Pfeiffer be given the maximum sentence. Pfeiffer was then sentenced to 180 days in the City Jail to think up new uses for chemistry.

Of course, deep within the library‘s quietude, one couldn‘t hear the bulldozers rumbling. Surely through the 50s they knew which way the wind blew, and it blew some silent but foul CRA halitosis through the cracks in the early 60s. By 1964 the Society was given notice, and eventually some blood money for the building and expenses incurred for moving and storage. In November 1968 the Society had moved out the last of their collection; shortly thereafter the bulldozers were deafening. The latticed windows and oak flooring and everything Independence Hall went crack and crumble.

Today, the Citigroup Tower (AC Martin Partners, 1979) sits atop the Hope Street site.

The library took everything and moved into the Granada Shoppes and Studios, where they remained until 1971. Unlike anything on Bunker Hill, the Lafayette Park area was left in blithe poverty long enough to allow this building to survive and become an HCM (read about #238 on BOL in a few weeks) and eventually National Register.

From there they hunted around and these Colonial folk found another Colonial building”¦though again, Spanish Colonial. Built as the Glendale Chamber of Commerce Building in 1929, 600 South Central Avenue–all 4,300 square feet of it–proved the perfect space, especially after the Society filled it with Windsor chairs, gas lamps and (American) Colonial flags.

Even if your lineage is more McCorkel than Mayflower, more B&O of Locust Point than Battle of Eutaw Springs, still, go to the library to check out their painting of Fremont painted from life. Too cool. It‘s small library nirvana for those of us with a library fetish.

Very special thanks to President Emeritus Richard Breithaupt for his kind permission to use these images and this information. The vast majority of this post is a reworking of this page from the Library‘s website. (A few of the small images are California State Library; the later view of the Stimson is an Arnold Hylen.)

Former saloon owner Joseph Gillek, 57, wasn’t a big fan of Prohibition, and like many other Angelenos he simply ignored the law. He’d spent the evening of February 25, 1928, drinking — most likely in one of the dozens of blind pigs operating in the city during that time. With the bootleg booze eroding his already dubious judgement, he compounded his unlawful behavior by getting behind the wheel of his car to drive himself home.

His muddled thinking resulted in a smash-up as he rammed his flivver into a retaining wall at his home at 201 South Bunker Hill Avenue. When his 30 year old son, Joseph Jr. came out to see what had caused the racked and saw his inebriated father lurch out of the automobile, he reamed the old man a new one. Once the shouting had died down Joseph Sr. burst into tears, declaring that he no longer wished to live.

Later that evening he went into the cellar with his revolver and shot himself to death.

May 22, 1930

William J. Stone, 38, was a Bostonian broker who’d moved to Los Angeles and into the Casa Alta Hotel and Apartments, 317 South Olive. In what may have partly been a case of Don‘t Argue with a Janitor, or partly No-One Likes a Broker in 1930, Stone managed to get into a regrettable debate with the Casa Alta janitor, one Walter Dixon.

The argument climaxed in Dixon taking a hatchet to Stone‘s head and chasing him from the building. Stone wound up in Georgia Street Receiving Hospital with severe skull lacerations, but lived to broker–or, not–another day, and Dixon landed in the stir on suspicion of ADW.

Here‘s everything you didn‘t know you needed to know about 317 S. Olive, aka The Kellogg, aka the Palace, aka the Casa Alta.

First of all, there are few photos of the place. Pity the poor Palace. It was too large and utilitarian to merit the lens of a Reagh or Hylen. Sure, everybody shot its neighbor, the Ems, and in nearly every Ems image, there‘s the Great Wall of Alta looming in the background:

(Don’t look at the Ems. Look at the building behind it. We’ll talk about the Ems next week, I promise.)

Moreover, whenever one stood on the corner of Third and Olive, the temptation was apparently too great to turn one‘s back on the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta and shoot the upper terminal of Angels Flight.

Before the advent of 317, it was 315 S. Olive, which was ground zero for the Burning Bushers.

Then came the seven-story, 84-apartment Kellogg. It opens in April, 1908.

Almost immediately it becomes the Palace Hotel and Apartments; the image at the top of this post, where it’s proudly emblazoned Palace Hotel, is from a card postmarked 1910.

Looking up Olive, ca. 1915: the most prominent, in ascending order, the Auditorium, the Trenton, the Fremont, and at top, the Palace:

In 1926 the owner puts it out to lease–it is snatched up and becomes the Casa Alta (they have cleverly renamed this rather tall house "tall house," but in Spanish!).

The 1929 City Directory:

Here‘s what we glean from this 1939 census report: the Casa, faced in brick, has 72 apartments (ok, so the Sanborn Map says 84) in its seven floors, and no business units. There‘s no basement. It was built in 1906, though that doesn’t exactly jive with its April 08 opening date. A nice two-room unit will set you back $27.50 ($406.55 USD 2007), still pretty cheap, but the Hill had begun its downturn even by 1939. Slouching toward shabby though it may have been, nevertheless, that rent was for a furnished apartment, and included heat, water, and electricity.

The 1956 City Directory:

…quite a few folk in the 72 apartments had ”˜phones. Two basement apartments, an office, eighteen tenants had the device. For Bunker Hill, that might have been some sort of record.

By 1965, there were fewer.

And that’s the last time it appears in the directories.

Here it is as one of the lone survivors, in its final days, ca. 1967. Angels Flight hangs on until 1969.

The Palace of Casa Kellogg, and its events of eventful eventfulness:

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace.

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace.

1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of Hotel Clayton (a literal stone‘s throw east at 310 Clay), Florence Cheney, testified. Florence Cheney‘s daughter, Margaret Emery, had her deposition taken at her Palace Hotel sickbed.

1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of Hotel Clayton (a literal stone‘s throw east at 310 Clay), Florence Cheney, testified. Florence Cheney‘s daughter, Margaret Emery, had her deposition taken at her Palace Hotel sickbed.

Margaret testified that Maude Kennedy had been in a fine and jovial mood until very shortly before her death, lending weight to the argument that she committed suicide (Tugwell eventually served ten years in Quentin for manslaughter).

Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas.

Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas.

We‘re all aware that every so often, people sometimes just up and go missing. Dr. Harold E. Roy was a prominent New York dentist whose crushed canoe was found in the Hudson River (it was assumed he was torn asunder by a paddle steamer); his widow moved to Los Angeles and into the Palace Apartments. Then, a year later, in February 1922, a lowly workman at the Kansas City Union Station realized, hey, I‘m a dead New York dentist. Where‘s my wife?  He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

The Palace Hotel/Casa Alta was also the center of political activity for rebel rousers from Riga. Through the late 20s the papers were peppered with small notices about, for example, the precise method of sending packages to Latvia, and if you had further questions, contact the Latvian Consulate–317 S. Olive.

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha!

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha!

![]() November 4, 1929. George McRoy, 31, was spraying the Casa Alta with insecticide–and nearly went to exterminator Elysium, but ended up at Georgia Street Receiving.

November 4, 1929. George McRoy, 31, was spraying the Casa Alta with insecticide–and nearly went to exterminator Elysium, but ended up at Georgia Street Receiving.

“I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death.

“I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death.

Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the Equitable Building, from where she made her own impression on Hollywood.

Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the Equitable Building, from where she made her own impression on Hollywood.

Two items were found in her pocketbook–a letter asking that her nephew be notified, and her eviction notice.

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34?

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34?

We may never know. All we know is that she was recently reconciled with her estranged husband, Willid Thompson. After two years she had returned to him, and for the past two weeks she and he were in domestic bliss at 317 S. Olive. That was, until, April 16, 1948.

Beatrice and Black knew each other from their place of employ, she a waitress, he a cook, at a downtown restaurant.

The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”

The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”

The Thompson killing by Black, who was black, gets surprisingly little press. Perhaps the concept that this interracial killing was presaged by an interracial love affair meant that propriety demanded ignorance.

As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

A month later, December 20, 1952, residents heard screams from the apartment of Willie Kohl, 79. His apartment was aflame; he was found on the floor near the bed, and died en route to Georgia Street.

Kohl’s conflagration is the Casa Alta’s final appearance in the Times. The remaining tenants are relocated in the late 60s and it soon becomes a tall pile of brick.

And atop the old site, the 1990 Omni Hotel, in which one can sense a vague hint of the old Alta. Vaguely.

Washington hatchet from here; bloody hatchet from Hatchet; Palace postcard, author; 1910 Ems, Los Angeles Public Library; 1960 Ems, Metropolitan Museum of Art; view up Olive, USC Libraries Digital Archives; census card, USC Libraries Digital Archives; Casa Alta with Angels Flight, Los Angeles Public Library. Bottom image you remember from Subject: Narcotics.

When last I peeked in on Bunker Hill’s First Congregational Church, its membership was planning a halfway house for reformed prostitutes and marching to protest Los Angeles’s crib district, a hub of semi-legal prostitution in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Now, it’s 1907, and things have been busy for First Congregational. For starters, they moved from the Hill in the early 1900s to 841 S. Hope Street.

But more exciting, the church’s Women’s Work Society has compiled a cookbook, Our Favorite Recipes, a remarkable collection of regional period recipes. Even more exciting, it’s been digitized at Archive.org, along with a number of other Los Angeles cookbooks from the early 20th century.

Perhaps we’ll celebrate this collection with a helping of Harriet Burd’s Congregational Pudding:

1 cup molasses

1 cup chopped suet

1 cup cold water

3 cups graham flour

1 teaspoon soda

Flavor with cinnamon, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and vanilla. Steam three hours in a three-pound lard bucket covered.

Or, on second thought, maybe we won’t.

Hats off to those contemporary “pulse-pounding” pictures what depict early-fifties dope and/or early-fifties Los Angeles for they are certainly the tingliest of films, though, let’s face it, they will never match the breathless, depthless pleasure of going straight to the source, of going straight to the Subject: Narcotics.

Subject: Narcotics. Though no movie critic has ever heard of it, Subject: Narcotics is the Greatest Film Ever Made. Do not confuse this film with Narcotics: Pit of Despair (also the Greatest Film Ever Made) or even Narcotic, which is no slouch either.

Let me say at the outset, unless you are a representative of our law enforcement community, you are not allowed to view this film:

So feel especially naughty in watching it, like sneaking into an R-rated picture when only sixteen. (Believe me, if the Narcotic Educational Foundation of America and their pal Lt. Ray Huber of LA County Sherrif’s Narcotic Detail were asked if the general public should be allowed to view this in fifty-eight years, they‘d say no. No.)

This picture has everything–prosties, junkies, pushers, neon signs:

LA: one big shooting gallery.

He lives from fix to fix and if he is lucky, he dies early, maybe from an overdose, maybe from an infected needle.

Shifty characters plan nefarious deeds on Court Street:

Til the coppers roar upon the scene:

The last part of the picture concerns a hype that gets sprung from stir, only to wander the rain-slicked streets of Bunker Hill (and be passed by a Roadmaster fastback):

He passes by the industrial heart of the Hill, Fourth and Olive —

And we turn and look behind him up to Third and Olive. Looming large and tall in the far distance The Palace Hotel, aka the Casa Alta, aka the Kellogg, at 317 S. Olive; below that, just at his shoulder, the Ems, at 337, and to the far left, the Olive Inn at 343.

Narcotics have weakened his character. Ninety-nine out of 100 slip back.

Alright already. Go watch Crime Wave.

And don’t tell Ray Huber what’s going to become of society.