They called it the red light district, the tenderloin, Little Paree, Hell’s Half Acre, and my favorite, the crib district.

From the late 1800s until the turn of the century, prostitution in Los Angeles was more or less legal, and centered in a district that included Alameda, New High, Main, and a few other streets in the area east of Bunker Hill. Most of the classier parlor houses that catered to wealthy and well-connected Angelenos were located on New High Street, including the one belonging to Los Angeles’s first storied madam, Pearl Morton. The brothels on Main Street were more modest, mostly rooming houses.

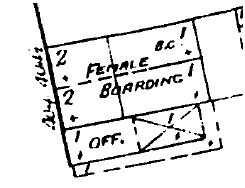

However, the most notorious eyesores were the single-story, ramshackle cribs on Alameda, long rows of narrow rooms that prostitutes could rent by the night, at exorbitant rates, designated here on the Sanborn maps as "female boarding." The Alameda cribs were visible from the nearby Southern Pacific line, and rail passengers on their way to Los Angeles would gawk out the windows at prostitutes soliciting business from the sidewalks.

However, the most notorious eyesores were the single-story, ramshackle cribs on Alameda, long rows of narrow rooms that prostitutes could rent by the night, at exorbitant rates, designated here on the Sanborn maps as "female boarding." The Alameda cribs were visible from the nearby Southern Pacific line, and rail passengers on their way to Los Angeles would gawk out the windows at prostitutes soliciting business from the sidewalks.

The prevailing line of thought among civil leaders and Los Angeles’s many, many police chiefs during this period was that prostitution was a social evil that could not be eradicated, but could be contained and regulated. Better to have vice located within a few city blocks rather than scattered throughout the city where it would be impossible to police.

Los Angeles residents, however, felt differently about it. In a June 1895 article, the Times reported that Police Chief John Glass had received numerous complaints from Bunker Hill residents complaining of the crib district’s proximity to their tony neighborhood.

And since the prostitutes were making fairly good money, and since crib living was both expensive and unpleasant, many prostitutes managed to pay the rent on their cribs and also rented lodging in nearby Bunker Hill hotels and rooming houses.

Due to its proximity, Bunker Hill would serve as a staging ground for the movement in the early 1900s to clear out the crib district. The social purity crusaders included the Reverends Wiley J. Phillips and Sidney Kendall, as well as Friday Morning Club founder Caroline Severance.

In 1903, about 200 Angelenos met at the First Congregational Church at Hill and Third to discuss building a halfway house for prostitutes who wished to reform. The facility, called the Door of Hope, opened on Daly Street in East Los Angeles later that year, around the same time that the movement was successful in getting the Alameda Street cribs shut down.

That mission accomplished, the social purity crusaders turned their attention to the parlor houses, a tougher nut to crack, partly because they kept a lower profile, and partly because they counted no small number of politicians, attorneys, and other civic leaders among their clientele.

The crusaders put these houses, including Morton’s at 327 1/2 New High Street, the Antlers Club, Stella Mitchell’s, and Viola’s Place, under surveillance, and pestered the Mayor and Police Commission until finally winning a small victory. At the end of March 1904, the parlor houses would be shuttered. Almost all of them went along with the ordinance, and the Times reported that "the keepers of dives did not wait for the police to call, but quietly folded their tents and departed."

All but one. All but one that had been operating right on Bunker Hill, not a block away from the First Congregational Church.

On March 31, 1904, police raided an establishment at 355 South Hill Street, operated by Ethel Wood. She was arrested along with three women, Mabel Stone, Dolly Long, and Hattie Jones. The four appeared in court the next day, all wearing long black veils to frustrate the looky-loos.

On March 31, 1904, police raided an establishment at 355 South Hill Street, operated by Ethel Wood. She was arrested along with three women, Mabel Stone, Dolly Long, and Hattie Jones. The four appeared in court the next day, all wearing long black veils to frustrate the looky-loos.

Wood was fined $100 for selling beer without a license, and the three women were "vagged," or charged with vagrancy, the usual charge for prostitutes until the charge of "offering" came into use in the 1920s.

After the raid, the other parlor houses reopened quietly, and would remain open for another four years. Pearl Morton, famed for her lavish parlor with two Steinway pianos, as well as her hourglass figure, flamboyant style, and hennaed hair, would be shut down in 1908, and move north to re-establish her operation in San Francisco.

The last quasi-legal parlor houses would close down in 1909, in tandem with the recall and subsequent resignation of Mayor Arthur Harper, a frequent brothel client.

And after that, prostitution did exactly what city leaders in favor of a containment strategy had predicted all along. It scattered throughout the city and into residential neighborhoods, before falling under the jurisdiction of organized crime in the 1920s.