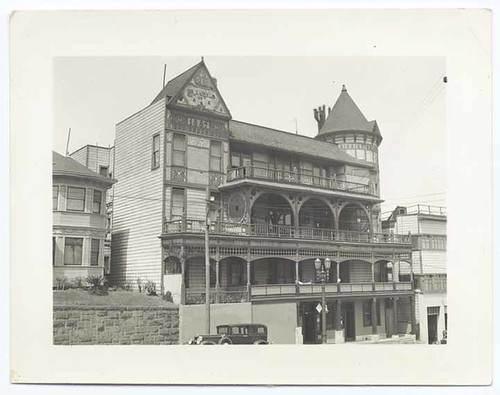

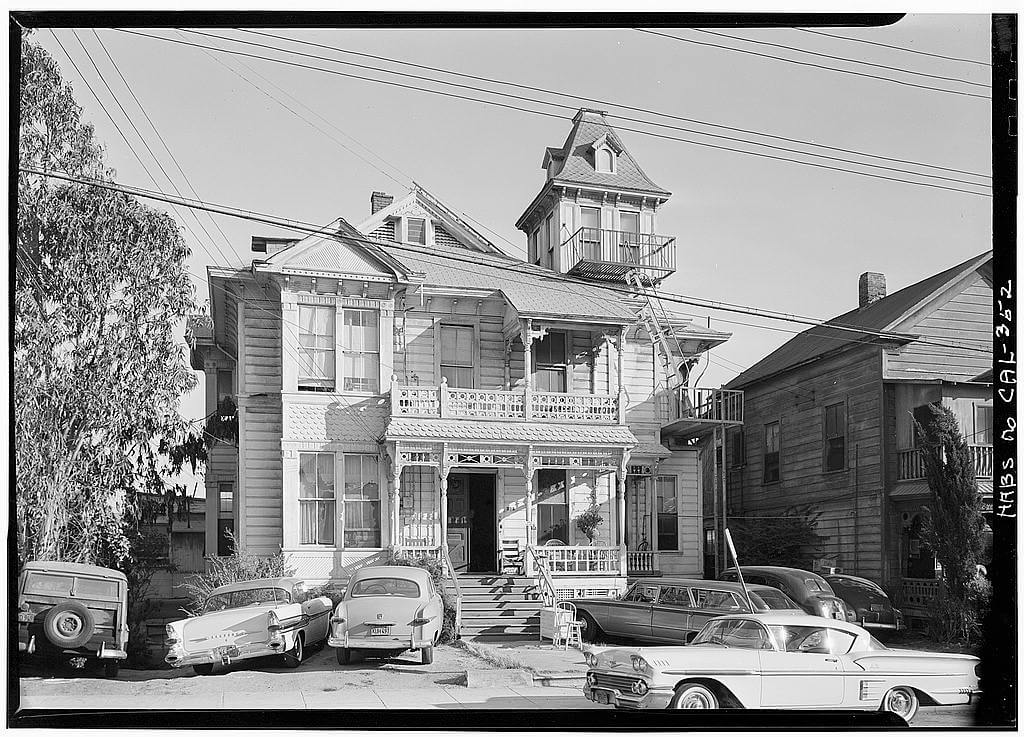

There was a place, once, a place people called home–the Hotel Elmar. Not much of a place, 230 rooms, built in 1926, facing a retaining wall, small matter of a 1953 shotgun holdup you‘ll read about, sure–but you see, it was the people that made the Hotel Elmar what it was. The Hot L Baltimore of its day. Of its dope-addled, nudie pinup, shotgun-toting Postwar day. Let‘s meet some of them now.

February 21, 1947. Our first resident of the Elmar, Ex-Cpl. Roy (Peewee) Lewis, 23, formerly of Joliet, Ill, is one of those war vets who came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles, the promise of the good life. You could become anyone. Your face could be up on the big screen! Plastered on billboards! Peewee at least got his plastered all over the corner of Ninth and Fedora.

February 21, 1947. Our first resident of the Elmar, Ex-Cpl. Roy (Peewee) Lewis, 23, formerly of Joliet, Ill, is one of those war vets who came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles, the promise of the good life. You could become anyone. Your face could be up on the big screen! Plastered on billboards! Peewee at least got his plastered all over the corner of Ninth and Fedora.

Lewis and his pal Paul Allen, 19, of 647 West 98th Street, were up in San Francisco a while back, where they managed to boost sixteen machine guns from the San Francisco Armory. Back in Los Angeles, they went on a taxi driver-robbing crime spree. Then they came upon an unusually hard piece of luck. While motoring along they espied a man who‘d just parked, drove by and gave him the eye a couple more times”¦this tickled the cop-sense of the car‘s occupant, Det. Sgt. Elmer V. Jackson, of administrative vice squad. He drew his pistol and held it under his coat.

Lewis approached, leveling a paratrooper‘s machine gun at Jackson. “I‘ll take that” were Lewis‘ last words, for though he was referring to Jackson‘s wallet, Jackson pushed the door open, knocking the machine gun aside, and Lewis took a service revolver blast to the face. Allen burned rubber and Jackson emptied his gun at the fleeing car.

Police found an Elmar Hotel room key on Lewis‘ body and they lit out for Hope Street, just in time to catch Allen leaving with his arms full of clothing. Allen–whose upper arm was grazed by one of Jackson‘s bullets–said Lewis had persuaded him to commit the holdups after meeting him in a bar, and Allen had agreed since he needed the money to marry a 17 year-old girl. So much for their next planned venture, which was knocking over a store at Slauson and Vermont.

November 14, 1947. Edna Grover, a raven-haired 20 year-old model, calls the Elmar home. But it was at the home of photographer William Kemp, 1830 Redesdale Avenue, where investigators from the DA‘s office found over 1,000 lewd photos of Edna. Kemp was fined $350 ($3,678 current USD) and given a 180-day suspended jail sentence, while our Elmarette was granted probation for her provocative posing.

March 21, 1952. Martin Salas, 23, left the Elmar‘s confines for an early morning spin this day. At Fifth and Main he hit a truck and injured the driver; he had an argument over right-of-way with a parked car at Sixth and Spring, and another wouldn‘t get out of the way at Third and Spring, and he had a metallic argument with another parked car at Second and Spring. Undaunted, he piloted smack dab into an RKO movie shoot at Third and Figueroa (Sudden Fear? Beware, My Lovely?) where a motorist that‘d tailed him flagged down a cop. The officer jerked open Salas‘ door, only to have Salas step on the gas, forcing the cop to run alongside until enough cops tackled the car and forced it to stop. At some point during Mr. Salas‘ wild ride he‘d had a passenger who ditched in an awful (in every sense of the word) hurry–hair was found on the windshield of the passenger side. Salas was booked on felony hit-and-run.

March 21, 1952. Martin Salas, 23, left the Elmar‘s confines for an early morning spin this day. At Fifth and Main he hit a truck and injured the driver; he had an argument over right-of-way with a parked car at Sixth and Spring, and another wouldn‘t get out of the way at Third and Spring, and he had a metallic argument with another parked car at Second and Spring. Undaunted, he piloted smack dab into an RKO movie shoot at Third and Figueroa (Sudden Fear? Beware, My Lovely?) where a motorist that‘d tailed him flagged down a cop. The officer jerked open Salas‘ door, only to have Salas step on the gas, forcing the cop to run alongside until enough cops tackled the car and forced it to stop. At some point during Mr. Salas‘ wild ride he‘d had a passenger who ditched in an awful (in every sense of the word) hurry–hair was found on the windshield of the passenger side. Salas was booked on felony hit-and-run.

March 4, 1953. Jack Hodges is 26, an unemployed aircraft worker, and lives a stone‘s throw from the top of Angels Flight at 314 South Olive. His pal Dean Coleman, 22, is in school to learn television repair, and bunks at the Elmar. When Coleman isn‘t in school, the two of them visit the local hotels. With their signature sawed-off shotgun and a briefcase. The only robbery Coleman didn‘t accompany Hodges on, of course, was the time Hodges robbed the night clerk of the Elmar.

Coleman‘s money wore thin and he‘d pawned his television repair apparatuses, and went shotgun-brandishing to get the stuff out of hock. Unfortunately for Coleman, Hodges pawned a stolen wristwatch, which led police to an old mugshot of Hodges; a little police work later and Hodges was caught in a bar at Sixth and Hill, his sawed-off shotgun and briefcase found in his Olive St. hotel room closet. He gave up Coleman, who was arrested while watching television in the lobby of 235 S. Hope.

Coleman, who studied dramatics before his decision to become a television repair man, was never meant to be a shotgun-wielding, hotel-clerk robbing gunman in real life. “As you see I don‘t appear to be a tough guy,” said Coleman, “but I can act the part when the occasion warrants.”

July 22, 1956. Elmar resident Frank Swope, 33, took offense at fellow Bunker Hiller Harold J. McAnally, 57–McAnally lived one block west at 230 South Flower–buying a lady a drink one summer day in a bar at 822 West Third Street. So Swope walked up and pushed McAnally from his stool, whereupon McAnally landed head-first on the concrete floor. A few hours after McAnally died from his skull fracture, Swope surrendered to authorities at the Elmar.

February 7, 1957. LAPD went to investigate a disturbance in a bar at 731 West Third and there arrested “Allan Ayers,” 32, a resident of the Elmar…

…turns out our Elmaree was in reality August Gerbitz, two years on the lam from a double murder rap in Evansville, where in December 1954 he gunned down his girlfriend, Mrs. Nadine Martin, 21, and one George Temme, 38.

March 20, 1957. Salvador Perez and Jesus Cruz, both 27, had been popped by narco and were up on the fourth floor of Police Administration, having been photographed at the lab. They were walked into the hallway by officers Hernandez and Ruddell to be cuffed and led to the first-floor Central Jail for booking.

That‘s when both of them made a break for it. Cruz, of 4923 Gratian Street, was tackled by Ruddell right out of the gate. Perez, he of 235 South Hope, dashed down the stairway. Officer Hernandez slipped and fell, broke his ankle, but continued to give chase nevertheless. Perez ran down to the ground level and made a wrong turn toward Central Jail, turned and ran past Hernandez, but unfortunately, into the arms of Lt. Arroyo. Another vacancy at the Elmar as Perez (and his buddy Cruz) are booked by an out-of-breath, broken-ankled cop on felony violation of the State Narcotics Act.

Kind of makes you want to check into 235 South Hope, doesn’t it? Perhaps you too can soak up enough of its magic to place you on this honored roll.

Kind of makes you want to check into 235 South Hope, doesn’t it? Perhaps you too can soak up enough of its magic to place you on this honored roll.

Alas, the City has wiped Hope clean, and thereafter had it thoroughly disinfected, as one would to so much egesta on a cracked tile floor. They have left us with the most barely readable of palimpsests. Let‘s take a look.

Hope Street had two levels between Second and Third; here, we are looking north toward Second, standing above the west end of the Third Street tunnel. The Elmar was midway along the block.

Today, the bilevel nature of Hope Street is five decades gone. The Ghost Elmar floats roughly above an intersection made by a new street, named after a Lithuanian-Ruthenian nobleman-turned-revolutionary. I betcha Frank Swope or Edna Grover never woulda guessed.

Today, the bilevel nature of Hope Street is five decades gone. The Ghost Elmar floats roughly above an intersection made by a new street, named after a Lithuanian-Ruthenian nobleman-turned-revolutionary. I betcha Frank Swope or Edna Grover never woulda guessed.

The City doesn’t screw around when they want something bad enough. They’ll move mountains, quite literally, to which these images taken across from the Elmar (looking south down Hope toward the library) attest:

The Elmar, gone, but perhaps now a bit less forgotten. For this blog is a little like the Elmar itself. Like it says on the cigarette pack. Wherever particular people congregate.

Hope Street images courtesy William Reagh Collection, California History Section, California State Library

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock. But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

Fortunately for the accused, he was “”¦something of a cousin to the renowned Senator Marcus”. The esteemed senator from

Fortunately for the accused, he was “”¦something of a cousin to the renowned Senator Marcus”. The esteemed senator from

have ended there ”“ but one more bizarre chapter remained to be written.

have ended there ”“ but one more bizarre chapter remained to be written.

February 21, 1947. Our first resident of the Elmar, Ex-Cpl. Roy (Peewee) Lewis, 23, formerly of Joliet, Ill, is one of those war vets who came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles, the promise of the good life. You could become anyone. Your face could be up on the big screen! Plastered on billboards! Peewee at least got his plastered all over the corner of

February 21, 1947. Our first resident of the Elmar, Ex-Cpl. Roy (Peewee) Lewis, 23, formerly of Joliet, Ill, is one of those war vets who came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles, the promise of the good life. You could become anyone. Your face could be up on the big screen! Plastered on billboards! Peewee at least got his plastered all over the corner of

March 21, 1952. Martin Salas, 23, left the Elmar‘s confines for an early morning

March 21, 1952. Martin Salas, 23, left the Elmar‘s confines for an early morning

Kind of makes you want to check into 235 South Hope, doesn’t it? Perhaps you too can soak up enough of its magic to place you on this honored roll.

Kind of makes you want to check into 235 South Hope, doesn’t it? Perhaps you too can soak up enough of its magic to place you on this honored roll. Today, the bilevel nature of Hope Street is five decades gone. The Ghost Elmar floats roughly above an intersection made by a new street, named after a Lithuanian-Ruthenian

Today, the bilevel nature of Hope Street is five decades gone. The Ghost Elmar floats roughly above an intersection made by a new street, named after a Lithuanian-Ruthenian

The NISA headquarters were located in the Lankershim Building at 3rd and Spring, and many of those arrested lived right on Bunker Hill.

The NISA headquarters were located in the Lankershim Building at 3rd and Spring, and many of those arrested lived right on Bunker Hill.

Among rank and file Depression-era Bunker Hill down & outers, Mr. A. E. Stotts was positive royalty among the sorry character contingent. Granted, he had the lovely Mrs. Stotts, and his apartment in the Alto Hotel at

Among rank and file Depression-era Bunker Hill down & outers, Mr. A. E. Stotts was positive royalty among the sorry character contingent. Granted, he had the lovely Mrs. Stotts, and his apartment in the Alto Hotel at  you a different story about swollen glands and night sweats and bloody sputum. Not to mention how the wife keeps sending him out to that sanatorium way the hell and gone in

you a different story about swollen glands and night sweats and bloody sputum. Not to mention how the wife keeps sending him out to that sanatorium way the hell and gone in

LAPD had recently installed radios in their cruisers, so officers Webb and Hamblin made it to the scene in a mere 90 seconds. The hapless perpetrator wasn”™t familiar with the latest crime fighting advances, and was promptly arrested and booked on a charge of burglary.

LAPD had recently installed radios in their cruisers, so officers Webb and Hamblin made it to the scene in a mere 90 seconds. The hapless perpetrator wasn”™t familiar with the latest crime fighting advances, and was promptly arrested and booked on a charge of burglary.

15-year-old Susie Miller was a pretty brunette with a vivacious disposition who loved to play the violin. She also loved Willie Miller, a 15-year-old butcher’s apprentice, and he loved her — the two were already talking about marriage. But Susie’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Miller disapproved of the match so strongly that they uprooted the family from their home in San Francisco and moved to Los Angeles in the hopes of squashing the love affair.

15-year-old Susie Miller was a pretty brunette with a vivacious disposition who loved to play the violin. She also loved Willie Miller, a 15-year-old butcher’s apprentice, and he loved her — the two were already talking about marriage. But Susie’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Miller disapproved of the match so strongly that they uprooted the family from their home in San Francisco and moved to Los Angeles in the hopes of squashing the love affair.