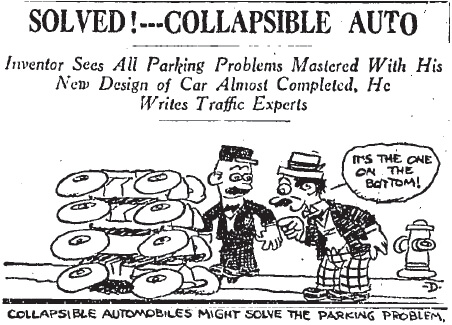

In January 1924, inventor Raymond Ragsdell of 202 South Grand wrote a letter to the Los Angeles Traffic Commission about his idea for a collapsible car that would fold down to the size of a go-cart. "With an automobile of this type it will be possible to park millions of cars where we are now able to park but a few hundred."

At around the same time, Eugene Egbert Dobbs of 303 South Hope Street wrote a letter of his own, proposing that all automobiles and street cars be barred from the downtown area (he laid out Sunset, Pico, Los Angeles, and Figueroa as the perimeter). In the letter he stated, "The only objection to this plan would come from those who are too lazy to walk. Now, our modern race is unhealthy due to lack of exercise. This barring of all transportation in the downtown district would force Los Angeles people to exercise, whether they wanted to or not, and thus, increase the length of life of the average citizen."

Sure, Bunker Hill residents may have had a vested interest in the issue, but in fact, the Traffic Commission received hundreds of ideas for congestion relief that month from people all over the city. Were they an invested citizenry? Untapped urban planners? The ancestors of the City Council that would ban fast food franchises in South Los Angeles over 80 years later?

No.

Unfortunately, they thought they were entering a contest.

An ad had appeared in local publications erroneously stating that the Traffic Commission would give a prize of $10,000 ($128,633 2008 USD) to the person who could solve Los Angeles’s burgeoning traffic problem. There was apparently some confusion, as the $10,000 in question had actually been appropriated by City Council for the formation of a Traffic Commission committee to look into issues of street parking and congestion.

The Los Angeles Traffic Commission was formed in 1922 in response to concerns about the city’s increasingly snarled and woefully inadequate roads. The group’s chairman said, "It is time for Los Angeles to solve her traffic problem… One can but guess at the conditions which will exist here within a few years unless relief is forthcoming."

Preliminary solutions to the problem were eerily similar to today’s: restricting parking in congested areas, requiring vehicles for hire to operate from private property, more one-way streets, and a subway system.

Following a report that traffic congestion on many Los Angeles streets was worse than New York City’s, a traffic relief ordinance was placed on the 1924 November ballot, allocating $5 million for the implementation of numerous streets projects and congestion relief programs, including the extensions of Figueroa and Olive from Bunker Hill into Elysian Park. It passed, but Mayor George Cryer vetoed it, and I promise, you will never guess why.

Actually, Cryer liked the ordinance a whole lot and thought it would be good for the city, but he vetoed it because he said it didn’t provide enough protections and accommodations for pedestrians.

Within a year, a new traffic plan was underway, and the city grid began to look a great deal more like it does today, but it does my Metro-riding heart good to know that even in 1924, someone was looking out for the walking man.