This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

The Sons of the Revolution–open to those with a lineal descent from those who fought for the Patriot cause (not as hard to get into as the Society of Cincinnati, but harder to get into than the Sons of the American Revolution, which wasn‘t founded til thirteen years after the Sons of the Revolution, for reasons I won‘t get into here)–seeks to forever keep alive the first men to fight for our treasured traditions. And perhaps because YOU had some great great somebody at Cowan‘s Ford, they keep a genealogical library so that you may do the necessary research into possible membership. Today, their 110-year-old collection has 30,000+ volumes kept open to the public, free of charge, in Glendale; but the road there has been bumpy, save for forty years of comparative calm on the Hill.

The Sons of the Revolution of California was founded in 1893, and by the turn of the century had some 5,000 volumes regarding the Revolution and Colonial America, especially in relation to the West. Its first establishment was in the offices of the Society‘s first President, Col. Holdridge Ozro Collins.  Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Bonebrake-Bryson Block (Joseph Cather Newsom, 1888), NW corner of Second and Spring, shown here before and after its remodel. It was further remodeled into an open pit, as its corner site is now where the 1948 Times Mirror Building stands.

The Society stayed in the Bryson Block from May of 1893 until June of 1894, when Collins moved his offices, and the library, into the brand-spanking-new Stimson Block (Carroll H. Brown, 1893), NE corner of Spring and Third.

The Stimson Block was the first six-story building in Los Angeles, the first steel frame building in Los Angeles, and the last major example of commercial Richardsonian Romanesque in Los Angeles when it was unceremoniously demolished for a parking lot in July of 1963. (We do have a good extant Victorian Richardsonian house”¦and it‘s also Stimson‘s.)

In any event, Collins and the library stayed at Stimson Block until it was decided that it was time for Col. Collins to get his room back, and for the library to have a place of its own.

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

But the Society kept growing, and a decade later–January, 1908–they were moving boxes into the San Fernando Building (John F. Blee, 1906), SE corner Fourth and Main.

They started knocking out walls on the sixth floor until additional stories were added in 1912 and the Society moved into quarters specifically designed for the library. By 1914, they outgrew even that and had to take on an additional room. Making matters worse (good for the library, bad for space concerns) was that Orra Eugene Monette, aka Mr. Bank of America, Society President, (Mayflower, Colonial Wars, Huguenot Society, ad infinitum) gave a large collection to the library.

Again showing their preference for new buildings, the Society turned their eye to the new Citizen‘s National Bank Building (Parkinson & Bergstorm, 1914) at the NE corner of Fifth and Spring; the building is still there, but has mysteriously been stripped of its architectural embellishments.

And there they stayed until Nathan Wilson Stowell donated to the Society a plot of land on Bunker Hill.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

When Stowell died in 1943, he was the last of the 20 charter members of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. (And although his forebear who came to Massachusettes in 1620 was named Samuel, and the rest of his mishpucha are variously named Abraham, Isaac and Israel, Nathan maintains he is a Protestant.) Despite his importance to the history of Los Angeles, or perhaps because of it, some cultural terrorist elected not to restore his name to the Stowell, which was renamed the Earle in 1950 after its acquisition by the Milner chain, and redubbed the El Dorado in 1955.

So Stowell donates the land to the Society and made a point of submitting his own plans for the building, to cost $25,000. In October 1927, they held a ceremonial groundbreaking to turn the first shovelful of earth:

Left to right: Lansing Sayre; Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens, Bishop of Los Angeles; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., California Society of Colonial Wars. 1926-27); Philip E. P. Brine; Dr. Daniel L. Ransom; James D. Hurd; Dr. Edward M. Pallette, President; Wilson Milnor Dixon, Librarian (holding shovel); Charles B. Messenger; Orra Eugene Monnette (waving hat); Charles F. Bouldin; Dr. Egerton Crispin; unknown; Cassius Milton Jay, Secretary; Col. Harcourt Hervey, Marshal; Edward Bouton, Jr.; Dr. James D. Eaton.

Left to right: Charles F. Bouldin; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., Colonial Wars); Edward M. Pallette, President, shaking the hand of Willis Milnor Dixon, Librarian; Lansing Sayre; John Emerson Marble; Orra Eugene Monnette (holding hat); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Cassius Milton Jay; Burnham Robert Creer (partially hidden); Edward Bouton, Jr.; unknown; Dr. James Demarest Eaton; and Dr. Daniel L. Ransom.

Left to right: Mrs. Frank Pettingell; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (U.S. District Judge; future Society President and General President Sons of the Revolution); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Bishop William Bertrand Stevens and Dr. Edward Marshall Pallette.

Above, on November 26, 1927, Dr. Pallete officiated at and Bishop Stevens conducted the services at the laying of the cornerstone. Within the cornerstone were deposited historic documents from the Sons and Society of Colonial Wars, along with 7th century Arabic manuscripts; a Spanish silver seal from the time of Ferdinand and Isabella; a California pioneer gold dollar of 1854, and a pass through the Continental lines issued in 1871 by the Supreme Executive Council of the Pennsylvania Colony.

The library opened to the public February 1, 1928.

They burned the mortgage in 1935:

Left to right: unknown; Lansing Sayre; unknown; Nathan Wilson Stowell; Willis Milnor Dixon; Orra Monnette; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (General Registrar, General Vice President, 1934, General President, SR, 1937); W. W. Beckett; James Black Gist; E. Palmer Tucker, President (sitting); Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens (Episcopal Bishop of Los Angeles, General Chaplain, General Society of the SR, 1940-1947); Dr. Edward M. Pallette; Egerton Crispin; unknown; and Cassius Milton Jay (Treasurer).

Now then, of the building.

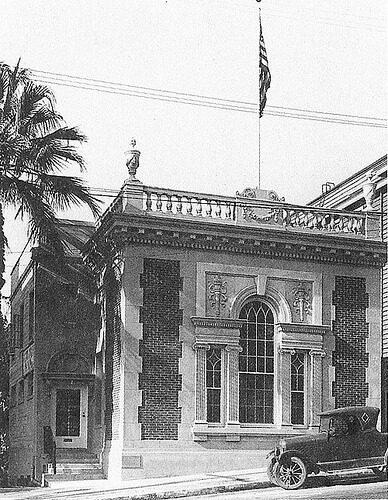

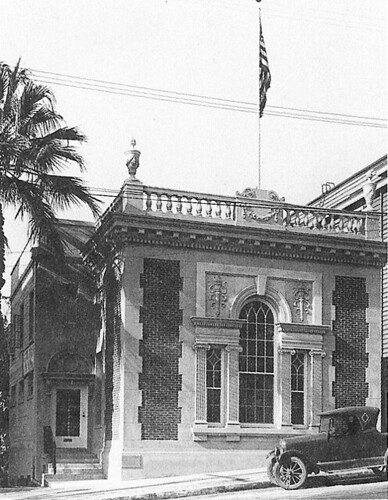

Let‘s talk Stowell‘s style. In the last ten months of OBH you‘ve seen a lot of structures, but nothing quite like this handsome dentil‘d and bequoin‘d Georgian. The Federal-style flat roof behind the balustrade, and that Palladian window”¦what does that remind you of? Come on”¦

Of course”¦what could be more appropriate than appropriating from Independence Hall?

Inside, what more could one ask for?

The secretaire with broken pediment, the Ionic capitals, the Doric pilasters, the plaster medallion, the comforting keystone? One can gain an almost perfect serenity from gazing into this image (imagining the hypnotic tick-tock of an Elias Ingraham on the mantel…kept me in ataraxia all these feverish months, allowing me to postpone this post to President‘s Day).

Another corner of quietude and sobriety:

The library opened its doors to other patriotic and hereditary societies, e.g. the Society of Colonial Wars, Order of Founders and Patriots, and the Mayflower Society; of course the DAR hosted more than a few luncheon n‘ lectures.

While the library naturally abjured the wild Bunker bacchanal, perhaps we should make mention that it did have some interesting neighbors (okay, so this post doesn‘t get away totally scot-free when it comes to tales of queer criminality).

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

437, between the Touraine and the Santa Barbara, before the 1927-8 Society building (Sanborn Map, 1906) and after (Sanborn, 1950):

Tales of the Tourained.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Mrs. Helen Roberts, Miss Eva Knoll, and Mrs. M. Brader, of the Santa Barbara Apartments, were three of the ladies who fell under his sway. They probably found him less dashing as they stood in court and identified various articles of jewelry, looted from their rooms in the Santa Barbara, found in de Marquette‘s possession.

He also made the rounds as none other than Donald Crisp, and supported himself by writing ficticious checks as the actor/director.

Turns out that he‘s just Leonell Gianini, a repeated youthful offender who‘d been sent to Whittier for burglary. His folks are ranch owners with a farm out in Ocean Park Heights (renamed Mar Vista in 1924). Nevertheless, in court, he claimed the jewelry as heirlooms “from his ancient and honorable family” in France. He got five years at Folsom.

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

At his trial, Pfeiffer denied contemplating a bank robbery. “I am a somnabulist,” he explained. “On the morning in particular, I walked in my sleep and went over to the table to write this note, which was found by the detectives when they called several hours later. It was all a dream. I dreamed that I had held up a bank.” Deputy City Prosecutor Ford Q. Jack, reminding the court that in several recent hold-ups the same method had been employed, asked that to curb the dream alibi in prospective bank robbers, Pfeiffer be given the maximum sentence. Pfeiffer was then sentenced to 180 days in the City Jail to think up new uses for chemistry.

Of course, deep within the library‘s quietude, one couldn‘t hear the bulldozers rumbling. Surely through the 50s they knew which way the wind blew, and it blew some silent but foul CRA halitosis through the cracks in the early 60s. By 1964 the Society was given notice, and eventually some blood money for the building and expenses incurred for moving and storage. In November 1968 the Society had moved out the last of their collection; shortly thereafter the bulldozers were deafening. The latticed windows and oak flooring and everything Independence Hall went crack and crumble.

Today, the Citigroup Tower (AC Martin Partners, 1979) sits atop the Hope Street site.

The library took everything and moved into the Granada Shoppes and Studios, where they remained until 1971. Unlike anything on Bunker Hill, the Lafayette Park area was left in blithe poverty long enough to allow this building to survive and become an HCM (read about #238 on BOL in a few weeks) and eventually National Register.

From there they hunted around and these Colonial folk found another Colonial building”¦though again, Spanish Colonial. Built as the Glendale Chamber of Commerce Building in 1929, 600 South Central Avenue–all 4,300 square feet of it–proved the perfect space, especially after the Society filled it with Windsor chairs, gas lamps and (American) Colonial flags.

Even if your lineage is more McCorkel than Mayflower, more B&O of Locust Point than Battle of Eutaw Springs, still, go to the library to check out their painting of Fremont painted from life. Too cool. It‘s small library nirvana for those of us with a library fetish.

Very special thanks to President Emeritus Richard Breithaupt for his kind permission to use these images and this information. The vast majority of this post is a reworking of this page from the Library‘s website. (A few of the small images are California State Library; the later view of the Stimson is an Arnold Hylen.)