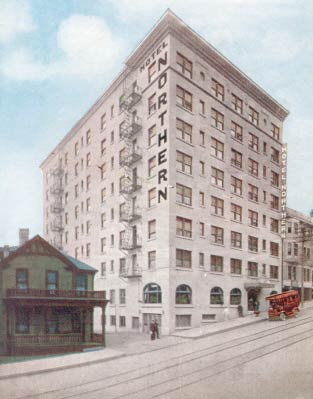

Above photo borrowed from the "A Visit to Old Los Angeles" website

January 13, 1913 was opening day for the Northern Hotel, a fireproof, 10-story establishment of 200 rooms with baths, built by F.W. Braun (wealthy president of the Braun corporation, dealers in assay and chemical lab equipment) and designed by his favorite architect W.J. Saunders.

It stood on the site of the old 3-story Carling Hotel, which the thrifty Mr. Braun ordered moved to the rear of a lot on the west side of Flower Street, just south of Court Street; Saunders was also reported working on a 3-story addition to the front of the old building to give it a modern face onto Flower.

During the early days of the year long construction (estimated cost $100,000), the Northern was reported to have been leased for a period of ten years for a rental of $200,000. This prompted one L.A. Times reporter to muse "the project is of especial interest as showing the sterling value of downtown frontage north of Fourth Street, revealing as it does the confidence of a leading capitalist in this older section of the city."

But things change quickly, even on old Bunker Hill, and by opening day leasee James Kincheloe was nowhere to be seen, with management undertaken by Frank L. and Blanche L. Crampton. The Cramptons were 20 year hoteliers, formerly of Seattle and Alaska. They most recently managed the Seminole Hotel on Flower Street. Sadly, their time at the Northern rang the final bell for their concord, for on Hallowe’en Eve 1916, Blanche peered through a transom and spotted Frank in the arms of another… a lady dentist! (Maybe she was just checking his bridge.) Blanche sued for divorce, noting that she had for some time been engaging detectives to follow Frank, but that she’d finally solved the case herself. After obtaining suitable visual evidence for the divorce, spry Blanche broke out the glass in the transom and climbed down into the dentist’s room, ordered her to put on her street clothes and marched the homewrecker right out of the hotel.

Conveniently located at the intersection of Second and Clay, the Northern was a reinforced concrete structure curiously designed with Bunker Hill’s eventual demise in mind. Its foundations, you see, ran thirty feet down, to permit the addition of two extra floors of rooms should the hill ever be shaved away. Other innovations included running ice water in every room, a central vacuum system, steam heat, hydraulic elevators for passengers and freight, telephones, and a French parlor for the ladies on the fifth floor.

Entrance to the hotel was made though the Second Street lobby, a fantasia in Italian marble, bronze, mahogany and tilework. The Mission furnishings were of red leather. From Clay Street, one could reach the dining room and grill, also fitted out in the Mission style, as well as the laundry and work rooms.

The Northern was not a year old when it found its first unquiet spirit. Anna, wife of Butte, Montana capitalist Jacob Osenbrook, came to Los Angeles with her husband and son Arthur to spend Christmas in the city. She had been suffering depression for several months, and it was hoped a change of scene and altitude would ease her worries. The family had just checked into their suite, and Jacob and Anna were standing at the sixth floor window, amusing themselves by comparing the number of passing motorcars to horses. Anna was a horse fan, and exclaimed loudly whenever one entered the scene. In the midst of the conversation, Jacob went to the next room to get a glass of water. When he returned, the curtains were outside the window… and when he looked outside, he saw that Anna had joined the horses below.

By May 1919, the Northern was under new ownership, having passed from the Union Realty Company to the Los Angeles and Santa Monica Beach Company. A news report curiously describes the building as a 9-story structure, but they may not have been counting the service basements.

Above: Hotel Northern from Second and Hill, 1920, photo from the collection of the LA Public Library

In July 1920 a bizarre incident unfolded at the Northern, when two little girls from Little Rock — Laura Cash and Margaret Martin ”“ arrived in Los Angeles and encountered a strange, ticked off lady who tossed a note addressed to Miss Martin into the room she shared with Miss Cash. It read: "Margaret Martin, it will not pay you to keep on with Levee. A word to the wise is sufficient. Mrs. Levee."

Above, Matilda Levee in repose

Baffled by this message, Miss Martin went off to take a stroll. It was then that Matilda, long estranged wife of attorney Frederick R. Levee, entered the Hotel Northern and returned to the room where she’d left the note, encountering there Miss Cash. Assuming Cash was Martin, as she had previously assumed Martin was messing with her hubby (later it was asserted that Martin’s visiting card was on Levee’s desk because his law partner knew her), Mrs. Levee brandished a cowhide whip and slashed Miss Clark five or six times across the face. Cash shrieked, of course, and her assailant fled. Where’s Eugene Corey when you need him?

Above, Matilda Levee in action

Mrs. Levee, formerly of 1001 South Union Avenue, was at the time suing her husband for divorce and maintenance, and had previously whipped at least two other women who she believed to be involved with Frederick, who had long since abandoned her. Previous victims include Mrs. Emma K. Doyle of Chicago, whipped at the Hotel Clark in December 1918, and Mrs. Inez M. Farnham, a cabaret singer from the Philippines, whipped in a hotel dining room and chased down Broadway while Frederick watched. Police quickly located Matilda in Santa Monica and held her pending civil charges which went unfiled, as the Arkansans had suffered sufficient embarrassment. (Inez never sued either.) Matilda was, however, brought up before the Lunacy Commission at the behest of Frederick, found to be "not absolutely normal, but not insane" (this is the new slogan of On Bunker Hill), and freed.

Frederick Levee meanwhile checked the wind and fled the state, abandoning his car in El Paso and continuing east by rail. He was arrested in New Orleans by agents of the Nick Harris detective agency in March 1921 and was to be returned to Los Angeles to face judge Walton J. Wood, who had just ruled in Matilda’s favor on their divorce and the $200 monthly alimony she sought, and who was not amused that Frederick had missed the court date. At this hearing, Matilda testified that they had failed to live happily as husband and wife, and that she had finally told him to "hit the ties and keep going" or she would "get" him. Previously, Frederick had protested "Why, she even shot a hole through my coat" to which the sassy Matilda snapped "Well, didn’t I buy you the coat?!" She’d also once visited him in his law office and shot him in the arm.

Somehow–maybe he told them what his home life was like?–Frederick gave the detectives the slip. By late April, the Levees were both in New Orleans, Matilda seeking to hasten Frederick’s extradition. On arrival, she discovered that he had established a law office in the Maison Blanche Building in Canal Street, and had obtained one of those sneaky Louisiana divorces without her knowledge. She fumed and stalked him.

Finally on May 7 she lurked near the St. Charles Hotel until he came out and saw her. They spoke briefly, and as he turned away she… what, do you think, whipped the heck out of him? Oh no, whips are for women. Husbands get the gun. Before hundreds of witnesses Matilda shot Frederick in the back, causing his death. Clapped in jail yelling that she had done it to save other women the pain she had suffered, Matilda pled not guilty, and later filed an injunction against Lucius H. Levy, administrator of Frederick’s estate, to stop him from disposing of any property.

In March 1922, Matilda was sent to the East Louisiana hospital for the insane at Jackson. (We reckon that they have a slightly freer definition of madness in the south than in the Southland.) Released as cured in June 1923, last reports have her seeking control of her late husband’s extensive property holdings in Texas and California.

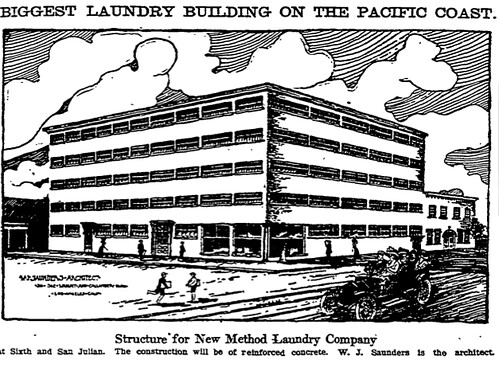

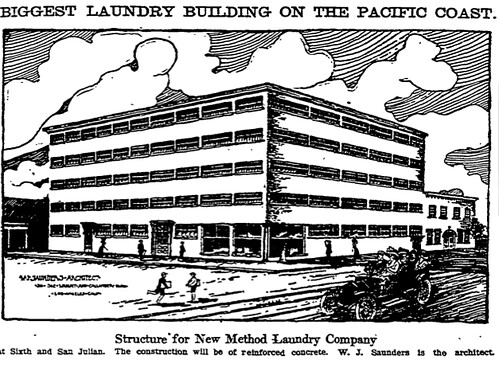

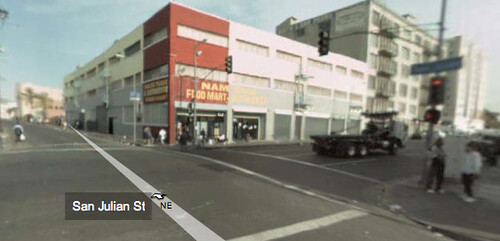

But we are far from the Hotel Northern and Bunker Hill now, with a tale of love scorned ending up in a Louisiana madhouse. What of architect W.J. Saunders, a reinforced concrete specialist who made his name building the downtown lofts and warehouses which garnered deep fire insurance discounts for his clients? Among his notable projects were a charming Mission Style auto sales and service shop on Orange Street (1921, see drawing above), the remodeled Lynn Theater in Laguna Beach (1930, still in operation, and variously described as being French-Norman and Mayan) and a supermarket at Wilshire and Camden Drive (1933) built for screenwriter Louis D. Lighton ("Wings," "It"). Among his surviving commercial structures is the massive five-story New Method Laundry Company plant on the northeast corner of Sixth and San Julian (1910, see below), featuring rows of novel windows that began at five feet above the ground and reached to the ceiling. It still makes a striking facade, despite a wretched paint job and a couple of missing floors.

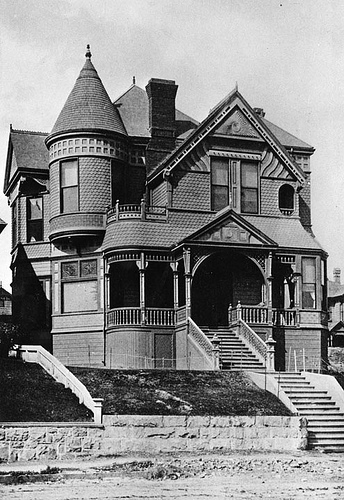

But for his most unusual structure, Saunders served as his own client. This was the "spite house," erected in 1907 at 2691 San Marino Street flush up against the property line of Saunders’ neighbor Adolph Lowinsky, orchestra leader at the Angelus Hotel. This oddity was two stories high but only one room deep, with its staircase on the outside wall and no windows on the west side.

Lowinsky sputtered that this abomination existed purely to deprive his home of any natural light on the east side, and to block the view from his porch; other homeowners shared his revulsion at the bizarre addition to their block. Saunders countered "I planned that house long before I ever knew Mr. Lowinsky. That is a flat building, and I believe it will prove lucrative!" And anyway, Lowinsky had started it by pelting the Saunders children with stones and building an unsightly wall. Lowinsky further claimed that he and his day-sleeping wife had long been tortured by the Saunders brats, who rolled past the house on the sidewalk on noisy wagons, banged tin pans under their windows and yelled "Sheeny" whenever Lowinsky mowed his lawn. Saunders complained that Lowinsky pelted his children with pebbles, cursed at his wife and finally pointed a shotgun at him and threatened to blow his brains out. These battling neighbors aired their grubby laundry in a series of newspaper articles, but seem never to have actually sued or slain each other.. no doubt much to the disappointment of you, gentle reader.

You can today walk in Saunders’ footsteps by joining his and the missus’ club, the Ruskin Art Club (founded 1888 and still active). But please be kinder to the guy next door.

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.  On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

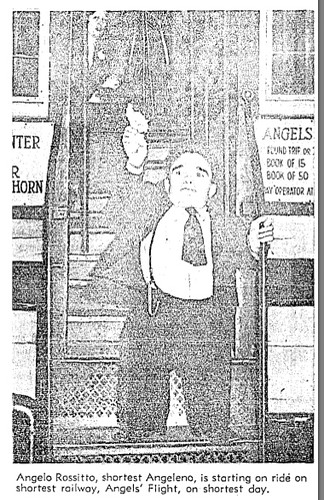

Bunker Hill‘s final days, after its Official Designation as blighted slum, evokes not only decrepit dandified buildings like the Dome, but also its downtrodden denizens, shuffling along, infused with all the despair and longing and hopelessness you‘d expect from folks in a blighted slum. It being Official, after all.

Bunker Hill‘s final days, after its Official Designation as blighted slum, evokes not only decrepit dandified buildings like the Dome, but also its downtrodden denizens, shuffling along, infused with all the despair and longing and hopelessness you‘d expect from folks in a blighted slum. It being Official, after all.