It’s not an Edwardian octoplex full of grime and grifters. It‘s not even on Bunker Hill. But we‘re going to tell the tale of the Architects‘ Building, and if not to you, faithful OBHer, then to whom?

All and sundry weep for the Richfield. It‘s not altogether true that everyone turned a blind eye during its”68-9 demo. Even the Government knew enough to come on out with its Instamatic and take lots of snaps.

The November 1968 Times article “Black and Gold Landmark: End Arrives for LA‘s Richfield Building” discusses those architecture students who believed the structure a remarkable example of “Jazz Moderne” worthy of preservation.

And the only mention of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth (which by 1968 had been renamed the Douglas Oil building) and which shared the block with the Richfield was as such:

”¦and that was the end of that. According to Cleveland Wrecking‘s general manager, the million-dollar site clearance project, of the block bordered by Fifth, Flower, Sixth, and Figueroa, was the largest ever undertaken in the West.

What is this Architects‘ Building of which we speak? Who architected this interbellum edifice?

Downtown is very nearly defined by Parkinson, and you can‘t mention LA without Morgan, Walls & Clements (Stiles sitting in the softest spot of this writer‘s heart), and if I mention Walker and Eisen, you‘ll say Yaaay! and I‘ll agree, and we‘ll high-five, and then get cut off and kicked out of wherever we are. It sure is swell to take those Conservancy tours and see all these places, but when the Conservancy cats go back to their digs, they return to a Dodd and Richards.

And you say, who?

William J. Dodd, student of Jenney and Beman is one of the great Midwestern architects. He came to California and is credited–though scholars still dispute to what extent–with a portion of Julia Morgan‘s 1914-15 Examiner Building. This he did with his partner at the time J. Martyn Haenke. In 1916 he partners with engineer William Richards. They produced so many an important Los Angeles structure that I will at some point in the near future add their full history as a comment appendage to this text, to keep from having too many appetizers before our twelve-story entrée.

We’re talking about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa, not to be confused with our friend on the kitty-corner to the northwest, the Monarch Hotel.

The first rumblings about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa come in February 1926, when mention is made of preliminary plans and lease negotionations for a million-dollar skyscraper to house LA‘s building trade. Sponsoring the project are Morgan, Walls and Clements, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, Webber, Staunton and Spaulgin, Carlton Monroe Winslow, Elmer Gray and McNeal Swasey.

The big announcement is made in February 1927 about the $650,000 height-limit to be built on the southeast corner of the Fifth and Figueroa. To be known as the Architect‘s Building, after New York and Chicago, it would be the third of its nature in America: a whole structure exclusively devoted to the various branches of the construction industries. It is to be of a “modified Italian” architectural treatment according to the associated architects drawing up the specifications: Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carleton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson.

Twelve stories high, with a site of 60 by 156 feet, it is to be of steel reinforced concrete, 143 offices, its exterior finished in plaster with cast-stone trimmings. Its seven upper floors of the building are to be leased to prominent architects, its first floor and mezzanine to be occupied by the Metropolitan Exhibit of Building Materials–a massive exhibit of every branch of the building industry, renamed the Architects‘ Building Materials Exhibit.

By November of 1927, the building was nearing completion. Preston S. Wright, president of Wright-Aiken, owners of the AB, ran down some of the tenants: Rapid Blueprint Company; D. C. Writhg, insurance; E. E. Holmes, insurance; William Simpson Construction Company, builders; Brian D. Seaver, attorney; and architects D & R, Coate, Johnson, Winslow, and William Lee Wollett.

816 opens in January, 1928. It came in at $662,000.

The depression would not be good to the Architects‘. It was foreclosed on its $360,000 outstanding bonds in February 1933. It was put under federal receivership and forced into a court-ordered sale, which didn‘t occur until May of 1938, when an F. V. Fallgren and associate could pony up the 300k to a trustee representing the bondholder‘s committee.

The Architects‘ Building survives just fine through the 40s and 50s.

One bit of drama: Evans Erskine, 34, a jobless Air Corps vet, figured that 1955 would be Year Last. He climbed to the ninth-floor fire escape of the Architects‘ Building and hoisted himself over the railing. Richard McGowan, a controller for Dames & Moore Civil Engineers, ran down the hall and and grabbed the hands of the nattily dressed, ledge-teetering Erskine poised 100 feet above Fifth Street. Here, McGowan reenacts his daring hand-grabbing:

In 1959 it is purchased by Douglas Oil, a southern California independent who run three refineries and 300-some gas stations in the Southland. It remains the Douglas Oil building despite Douglas‘ purchase by Continental Oil (AKA Conoco) in 1961.

It‘s the 1960s when the folk in 816, heck, the building itself, could hear the dirge of doom wafting on the wind. Listen, it‘s coming from over by the Richfield building.

Richfield, another oil company, who owned that big ol‘ black and gold tower to the south, had merged with east coasters Atlantic Refining in 1966. Richfield had already begun buying up the block for piecemeal parking, and as Atlantic-Richfield Co. they purchased the whole kit. And kaboodle. That called for the end of the Architects‘, as ARCO intended to build not one but two Miesian towers (though their New York twin-tower counterparts broke ground four years earlier, there appears to be an aesthetic epoch between AC Martin’s work and Yamasaki’s tube-frame twins of lower Manhattan, whose postmodern sensibility stems from a neo-Gothic use of aluminum).

1967, and all‘s well:

1969, during the demolition. The Architects‘ Building, now one-fifth off! The Richfield, now with two-thirds less Richfield!

1970, towers going in.

Left to right, the Tishman Building (Victor Gruen, 1960, though you know it like this), Glore Forgan Staats, the Gates Hotel (now a fine Brooks Bros), St. Paul‘s Cathedral (razed), the Hilton (note how it changed from the Statler to the Hilton between 67 and 69), the Jonathan Club , the Carlton Hotel (razed), Caldwell Banker.

Below, today. Note the wee bit of the Jonathan peeking out.

The ARCO Towers still stand in all their glory. For now.

Another shot of the demolition. The Sunkist, Engstrum and Edison line Fifth. The Telephone Tower on Grand. In the distance, left, Bunker Hill Towers going up.

A mid-60s aerial. Central Library bottom right. The Sunkist at Fifth and Hope. Halfway up Hope behind the Sunkist, the tiny Sons of the Revolution and the Santa Barbara. The big apartment building at the southwest corner of Fourth and Hope was the Barbara Worth.

Of course we’re not getting away without the requisite model and Sanborn additions:

Note how Fourth Street ends at Flower. Compare to the 60s aerials which indicate the magnitude of the 1954 Fourth Street Cut.

Just to clear up one bit of confusion. Despite early mention that this building was to be of the combined effort of Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carlton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson”¦it‘s a Dodd and Richards. Even Adrian Wilson, who in April 1967 wisecracked “I hope our new location won‘t be so temporary” in an article about his having to move out of the AB after thirty-nine years, remarks that Dodd and Richards designed the building–and he should know, the plans for 816 are inscribed with his own initials, as he was their draftsman before he hung out his own shingle when the building opened in 1928.

Clockwise from the south: Sixth, Figueroa, Fifth, Flower:

That then is the tale of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth. Remember the diaspora the next time you‘re in the neighborhood.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library photo archive, University of Southern California, and Arnold Hylen and William Reagh Collections, California History Section, California State Library

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse,

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse,

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to  1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace.

In 1914, the Palace Hotel was where fancy ladies with big diamonds lived. Therefore, of course, sharps and cons knew where to prey. But Lillian Walker was ingrained with common sense and uncommon suspicions. Despite the big car with its monogrammed door, from which stepped the elegantly dressed man and woman who came to her apartment, despite their discourse about rare gems they‘d purchased in the orient, and their winter home in Santa Barbara, Mrs. Walker just doesn‘t trust people who blink rapidly when they talk. The man, who called himself Mullins, eagerly wrote her a fat check for a big diamond, but Mrs. Walker, seeing his blinky eye, said no. She took a $25 check for a small gem, and agreed to meet later to discuss further sales. She immediately verified her suspicions–the checks were false, and Lillian called the authorities–but the grifters got wise to the ambush set for them, and evaded being captured in the Palace. 1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of

1916 ”“ you may remember the Percy Tugwell case, in which the proprietor of  Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas.

Christmas Day, 1918, Katherine Lewis quarreled with her husband Lester Lewis. She had been despondent ever since having departed Richmond, VA for Los Angeles; the best course of action, decided Katherine, was to eat bichloride of mercury tablets in their Palace apartment. The physicians at Receiving Hospital fixed her up just enough to try another Christmas. He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

He tracks her down through her family and shows up on the Palace doorstep, and she has to give back $10,000 ($122,730 USD2007) to Bankers Life Insurance Company.

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha!

Now, Ethel M. Rising had a thing or two to say about marrying into Baltic bliss. She divorced her husband, H. R. Rising, left him in the Casa Alta, and the State awarded her $50 a month from H. R. to support their two daughters. But with that dictate Mr. Rising did not comply. Ethel complained to the City Prosecutor, who hauled Rising into court, October 2, 1928. There declared Rising: “I have been appointed Vice-Consul for Latvia and your courts have no jurisdiction over me.” The court conferred with the District Attorney and Rising was, in fact, correct. One can only imagine he threw back his head and added a hearty Latvian bwa-ha-ha-ha! “I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death.

“I‘ve been taking it on the chin for five years. My chin won‘t stand it any longer–” and, after penning that short note, and adding three $1 bills for his daughter in Vancouver, sixty-five year-old relief client Frank W. Blumie climbed to the top of the Casa Alta, December 1, 1935, and leapt to his death. Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the

Christmas cards to Mrs. Cecilia MacKinnon Moore are being marked returned to sender this holiday season. After being told by the Casa Alta landlord to vacate her quarters, she made her way on December 23, 1947 to the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine and to the top of the

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34?

What was the relationship between Mrs. Beatrice Imogene Thompson, 23, and Sylvester Black, 34? The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”

The pair boarded an LA Transit Lines car at 11th and Broadway, and for a while argued in low tones. She was against the window, sobbing, and muttering “Leave me alone, please leave me alone.” When she rose to leave at 4th and Broadway, Black pushed her back in the seat and shot her four times. Also on the car was James F. Patrick, Special Officer, Metro Division, who pulled his piece and handcuffed Black at gunpoint, during which Black pleaded “Shoot me, please shoot me.”  As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

As mentioned above, the Kellogg/Palace/Casa Alta had its relationship with the Central/Clayton/Lorraine via the mother/daughter team in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial. The two hotels also have cranky boilers. The Central tried to blow itself up in November 1953; the year before, in November 1952, the Casa Alta boiler felt the hands of Frank Dauterman, 43, tinkering within its works. So the boiler blew itself up, failing to kill Dauterman or take down the Alta, but sending Dauterman to Georgia Street with second and third degree burns to his head, chest and arms.

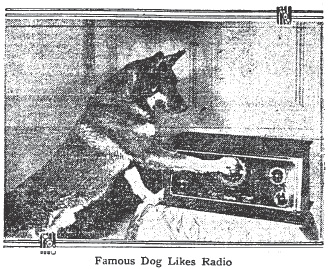

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

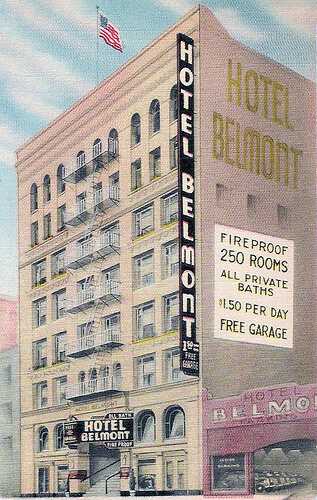

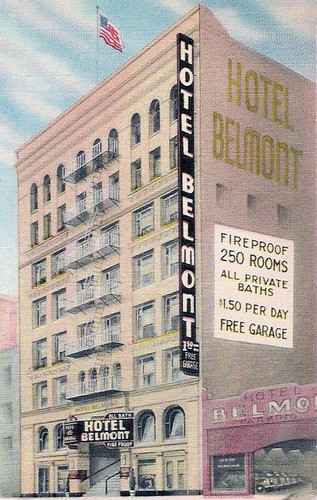

elevator operator William Patterson, who struck Edwards with his stool (that is, the small stool he sat on in his elevator) and knocked the knife from his hand. Rader struck Patterson with the butt of his gun; the robbers then tangled with 65 year-old Belmont desk clerk A. B. Cramer and eventually fled the scene empty handed–even more so than they came in with, as one of the crew lost their wallet, and they were all easily traced to a downtown roominghouse and arrested.

elevator operator William Patterson, who struck Edwards with his stool (that is, the small stool he sat on in his elevator) and knocked the knife from his hand. Rader struck Patterson with the butt of his gun; the robbers then tangled with 65 year-old Belmont desk clerk A. B. Cramer and eventually fled the scene empty handed–even more so than they came in with, as one of the crew lost their wallet, and they were all easily traced to a downtown roominghouse and arrested.

In January 1938, Mrs. Veronica De Shon Miller, 47, recently of Kansas City, divorced, despondent over the death of a friend, and an out-of-work beautician to boot, soaked a towel in ether and smothered herself in her Belmont flat. She was saved there by a friend. Fearing that the Belmont was conspiring to keep her alive, she left a note regarding the disposition of her belongings and made her way to the building at Fourth and Broadway where she once operated a beauty parlor, and flung herself to the concrete floor at the bottom of the light well.

In January 1938, Mrs. Veronica De Shon Miller, 47, recently of Kansas City, divorced, despondent over the death of a friend, and an out-of-work beautician to boot, soaked a towel in ether and smothered herself in her Belmont flat. She was saved there by a friend. Fearing that the Belmont was conspiring to keep her alive, she left a note regarding the disposition of her belongings and made her way to the building at Fourth and Broadway where she once operated a beauty parlor, and flung herself to the concrete floor at the bottom of the light well. September 28, 1942. Dr. Robert E. Hunsaker, 45, was due in court to face a hearing in a suit filed by his third wife for divorce. So he got a room at the Belmont. Top floor. Desk clerk Bernardo Sargil noticed Hunsaker on the window ledge and called the cops; when they got there they found dancer Ruth Rex in his room, pleading with him not to jump. The cops tried to grab him but Hunsaker ordered them back; finally he said “So long boys, this is getting tiresome,” and loosened his grip, falling the length of the building to meet Hill Street below.

September 28, 1942. Dr. Robert E. Hunsaker, 45, was due in court to face a hearing in a suit filed by his third wife for divorce. So he got a room at the Belmont. Top floor. Desk clerk Bernardo Sargil noticed Hunsaker on the window ledge and called the cops; when they got there they found dancer Ruth Rex in his room, pleading with him not to jump. The cops tried to grab him but Hunsaker ordered them back; finally he said “So long boys, this is getting tiresome,” and loosened his grip, falling the length of the building to meet Hill Street below.

1950: Behold, the 1907 YWCA, though it‘s been the Belmont now for twenty-five-some years. St. Helena‘s was redubbed “My Hotel” and has a liquor store in its corner. The structures to the east have been wiped for parking; the Kensington is now the Belmont garage. Above, the Astoria has a neighbor, the 1916 Blackstone Apartments.

1950: Behold, the 1907 YWCA, though it‘s been the Belmont now for twenty-five-some years. St. Helena‘s was redubbed “My Hotel” and has a liquor store in its corner. The structures to the east have been wiped for parking; the Kensington is now the Belmont garage. Above, the Astoria has a neighbor, the 1916 Blackstone Apartments.

A fire that would have felled a lesser building broke out November 3, 1967. The sixth-floor room of John Riles, 69, believed to have been smoking in bed, went up in flames, engulfing a good bit of that floor and part of the seventh, and all of the late John Riles.

A fire that would have felled a lesser building broke out November 3, 1967. The sixth-floor room of John Riles, 69, believed to have been smoking in bed, went up in flames, engulfing a good bit of that floor and part of the seventh, and all of the late John Riles.

Find the big red awning–across from the MTA bus parked at the Third Street curb–jutting out from

Find the big red awning–across from the MTA bus parked at the Third Street curb–jutting out from

In that our post about the earth carvings (the Cuscans have nothing on us) at Second and Hill garnered some interest, I thought it worthwhile to detail salient features and goings-on sundry of other buildings on the block.

In that our post about the earth carvings (the Cuscans have nothing on us) at Second and Hill garnered some interest, I thought it worthwhile to detail salient features and goings-on sundry of other buildings on the block.

Not a lot of Postwar noirisme at the El Moro, if you‘re after that sort of thing. Mrs. Mollie Lahiff, 50, died of (what the papers termed) accidental asphyxiation after a gas heater used up all the oxygen in her tightly sealed room, February 26, 1953. Should you be so inclined, consider how drafty these places tend to be. Tightly sealed takes some doing. Just saying.

Not a lot of Postwar noirisme at the El Moro, if you‘re after that sort of thing. Mrs. Mollie Lahiff, 50, died of (what the papers termed) accidental asphyxiation after a gas heater used up all the oxygen in her tightly sealed room, February 26, 1953. Should you be so inclined, consider how drafty these places tend to be. Tightly sealed takes some doing. Just saying.

A favorite phrase of Edwardian Angeles is “sneak thief,” and Bunker Hill sneak thieves were forever securing some silver coinage here and a jeweled stick-pin there; on August 17, 1903, for example, during Mrs. H. Ware‘s temporary absence from 132, a sneak thief entered and stole $10 and a gold watch (a similar burglary occurred that same day, where at 104 S. Olive a room occupied by Mrs. Case was ransacked and liberated of $20).

A favorite phrase of Edwardian Angeles is “sneak thief,” and Bunker Hill sneak thieves were forever securing some silver coinage here and a jeweled stick-pin there; on August 17, 1903, for example, during Mrs. H. Ware‘s temporary absence from 132, a sneak thief entered and stole $10 and a gold watch (a similar burglary occurred that same day, where at 104 S. Olive a room occupied by Mrs. Case was ransacked and liberated of $20).

July 30, 1954. Jesus Chaffino is a 2 year-old with a talent for opening doors. Apparently his mother, Maria Avila, didn‘t tell her sister-in-law that when she left her place at 121 North Hope and dropped of the Jesus at 132 S. Olive. He was turned over to juvenile officers when he was found wandering near First and Olive at five a.m.

July 30, 1954. Jesus Chaffino is a 2 year-old with a talent for opening doors. Apparently his mother, Maria Avila, didn‘t tell her sister-in-law that when she left her place at 121 North Hope and dropped of the Jesus at 132 S. Olive. He was turned over to juvenile officers when he was found wandering near First and Olive at five a.m.

July 16, 1907. A burglar was detected working the window at Mrs. M. M. Clay‘s apartment house, 425, by her daughter, Clara Clay. She exclaimed under her breath to a Mr. Charles See, who kept the apartment above hers, “There‘s a man trying my window.”

July 16, 1907. A burglar was detected working the window at Mrs. M. M. Clay‘s apartment house, 425, by her daughter, Clara Clay. She exclaimed under her breath to a Mr. Charles See, who kept the apartment above hers, “There‘s a man trying my window.”