Thomas Major Jr., 34, a logger by profession, down from Vancouver to take in the town. He was in the barroom at the Rollin Hotel, Third and Flower, when the cops came in to investigate a brawl, January 24, 1960. They have a funny way of doing things up in British Columbia, apparently, for as the bulls were bracing some other bar patron, Major pulled out a gun, pointed it at the cops‘ backs, and began pulling the trigger. The cops heard the click-click of two empty chambers, turned, and fired seven shots at Major.

Major was hit seven times, taking four in the abdomen. Detectives Pailing and Buckland, with Municipal Judge Griffith in tow, made a visit to Major‘s bed in the prison ward at General Hospital, where they charged him with two counts of assault with intent to commit murder and one of violating the deadly weapons control law.

The GH docs had pulled all sorts of lead from Major, but there was still the matter of the bullet in Major‘s heart. Yes, normally a slug from a Parker-issued K-38 in the ticker is going to put you down for good. But this one found its place there in an unsual way; one of those bullets to the abdomen apparently passed through the liver, entered a large vein and was pumped into the upper right chamber of the heart, passed through the valve to the lower left chamber, an in that ventricle there it sat. Apparently you can‘t just leave well enough alone, so someone had to go in and get the damn thing.

Enter Drs. Lyman Brewer and Ellsworth Wareham, of the College of Medical Evangelists. They‘d removed plenty of bullets from hearts using the old “closed-heart method,” but here thought they‘d try something new–having a heart-lung machine on hand, they thought they‘d throw that into the mix. No more working without seeing what you‘re doing: with the heart-lung machine, the heart could be drained of blood, and the surgeon can see and feel what‘s transpiring.

Dr. Joan Coggin, who assisted, also noted that they‘ve established a new approach to heart surgery in that they incised the heart on the underside, and not in the front; the electrical pattern of the heart, as evidenced by their electrocardiogram, has shown that this method results in far less serious consequence to the heart during surgery.

All this medical breakthrough, and all because some liquored Canuck on Bunker Hill decided to blast away at the heat! Should you wish to know more about this miracle of science, why don‘t you ask Ellsworth?

A bit on the Hotel Rollin, as long as we‘re here. Its building permits are issued July 9, 1904. Its two and three room suites are each furnished with bath and kitchen.

Those of you with the eagle eye will notice the Bozwell and St. Regis just in the background:

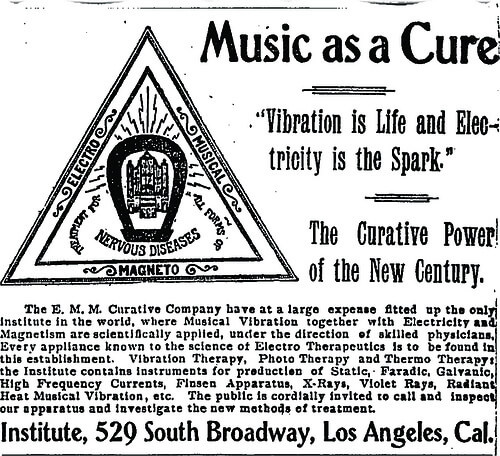

(Of course, the Hotel Rollin had a musical combo that entertained guests, and to this day many people remember the Rollin‘s band.)

Hotel Rollin image, USC Digital Archives