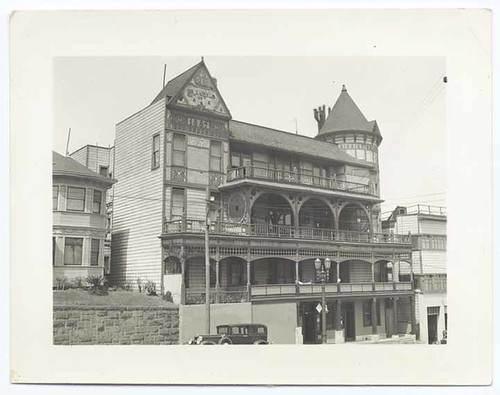

The Hotel Trenton, seven stories of sober brick laced with fire escapes, its yawning central maw somewhere between a gate of hell and a jaunty fireman’s doorway, lurked low on Bunker Hill for many decades. There it is at 10 o’clock in the panorama. It was not a racy hotel, but it had its moments, and left an imprint on the fabric of its times.

And speaking of imprints, it was July 1905 when a lady guest of the establishment marched into to the Los Angeles Times offices to report her dismay at having ruined her long white skirt, white stockings and slippers when she walked over the streetcar tracks at First and Broadway and picked up a liberal helping of petroleum, which the cars’ operators had smeared on the rails to deafen the screech which otherwise came whenever a curve was taken. A snarky Times reporter noted that had the lady been as eager to lift her skirts when crossing the tracks as she was to show off the damage caused by the oil–"and it’s higher up, too!"–she would not be in such a predicament.

In May 1906, town gossips received confirmation of a scandal, but too late to shun anyone involved. Some months earlier, Mrs. Genevieve Hughes arrived in Los Angeles from Denver and took rooms in the Trenton, where she was paid significant attention by fellow guest, Boston lawyer Charles W. Ward. Ward was briefly a Harvard man who took his degree from Columbia, a gymnast, a Knight Templar and a soldier, every inch the eligible young fellow… well, almost. Again and again he would ask that she marry him, and always she would demur–but not refuse his friendship. On February 28, Ward went into his room and shot himself in the head, and the whispers said it was out of thwarted love for Genevieve. The lady, however, had eyes for another, and quietly married A.G. Jones, also of Boston, departing for an Eastern honeymoon before news of the nuptials spread. And as for Ward, he was, it proved, a bounder, having left a wife and children awaiting the return of his health under the Californian sun. He lingered a few days after being shot, but died before his father could arrive by train.

In November 1907, Mexican Secret Service officer (and soon-to-be fink in the trial of revolutionary countrymen Magon, Rivera and Villareal) Trinidad Vasquez left the safe harbor of the Trenton for a meal in a restaurant at Fifth and Olive. He had a ham and cheese sandwich and a cup of coffee, returned to the hotel and walked out again. In front of the Police Station, Vazquez was stricken with symptoms of poisoning and rushed to Receiving Hospital, where his stomach was pumped. Relieved, Vasquez testified that soon after eating he had felt a sense of suffocation, then felt as though his very heart would burst before blackness washed over him. He was soon released, doubtless with a greater respect for the fervor of the anarchist community of Los Angeles.

In early February 1909 it was revealed that the Trenton’s recently hired night clerk Harry Stevens was in fact Florin G. Lee, a Riverside lad who’d suffered a breakdown from overwork (dry goods clerking by day, electrical engineering study by night) or, some whispered, love unrequited, on December 30 and fled his home, shaking off all memory of his former life. When confronted by old friends, who said they knew him well, Stevens/ Lee expressed astonishment, and mused on his happier times in Iowa and Butte, Montana, and his New Years Day rail trip to Los Angeles over the Salt Lake Route. Conveyed to Riverside, he looked with bemusement upon his aged grandmother and treated the rest of the family with cordial unfamiliarity. He did not recognize the shop where he clerked for nine years, the books he had kept (quite well) or respond to the music which he formerly had loved. For two months, the stranger stayed on in Riverside as those who loved him tried to spark a memory of his past life. And then suddenly, on April 2, while in the dry goods store where he had long labored, Florin’s memory of his accounting work came flooding back. He raced to San Bernardino to share the happy, mathematical news with his father, and we hear no more about him.

On the evening of August 6, 1912, an "elevator pilot" was sent down to the basement to fetch some ice water. On the way up poked he his head out as the cage made its ascent. The ice water went everywhere, and so did the poor lad’s cranium. So complete was the destruction that there was initially some confusion when night clerk E.G. Merrifield came on the scene as to whether the dead man was Charles J. Oberman or his colleague, Earl Ansley. The victim was actually, it transpired, Earl McDonald, 18, from Riverside, who was moonlighting under the name Earl C. Ansley at the Trenton and working a day shift at the Hotel Victoria at Seventh at Hope. It was his first night on the job, and hotel manager R. Hughes was later charged for violating the state law requiring all elevator operators be properly licensed.

On February 3, 1913, S. W. Westmeyer, a successful mining man from Globe, Arizona, visited his wife at the Trenton and wrote her a check for $1025. From there, he went to the Hotel Redondo in Redondo Beach, where, the following evening, he shot himself in the head. Westmeyer left notes giving his personal effects to his wife and asking that his Lodge, Rescue No. 12 of the International Order of Odd Fellows in Globe be notified of his passing.

Later that month, the Trenton figured in the notorious jury tampering case of the great attorney Clarence Darrow, who rang up large charges at the hotel for select jurymen, far in excess of the $9 weekly rate that investigators were quoted–though it was the thirty dollars in ten cent cigars that got the jury’s goat.

In October 1915, resident Marie Kinney announced that she was moving her dressmaking parlor from the Fay Building at Third and Hill to the Trenton, and noted that help was wanted. A year later, she announced her winter reopening in suites 102-103-104, crowing "choicest novelties in stock." Marie must have liked the place, for it was still her home on Valentine’s Day 1941, when, aged 80, she stepped in front of a Pacific Electric car on Huntington Drive near Poplar in El Sereno, and was killed instantly. Her rosary was said at Cunningham & O’Conner at 1031 South Grand, requiem mass held at St. Vibiana’s and she was interred at Calvary.

In October 1917 the Los Angeles Division of the Collegiate Periodical League began a monthly drive to collect 5000 magazines, none older than ten days, for distribution among the servicemen at Camp Lewis. Among the district captains was Mrs. Alice M. Bryant of the Hotel Trenton. Your blogger will now attempt to staunch the drool inspired by the thought of what was gathered.

Late on December 2, 1930, the Trenton was among a trio of downtown hotels robbed by a pair of bandits in a taxicab. After they hit the Stillwell at 9th and Grand for $30 and a pair of guest handbags, unknowing driver George Kruger waited patiently outside the Trenton while night clerk A. E. Finnity and manager Herbert Perry were relieved of another $30. Finally the Victor Hotel at 616 South St. Paul was victim, and again yielded up a lucky thirty simolians. The thieves then paid their ferryman and slipped off into the night.

By 1933, we note that rooms were being let for a modest $3.50 a week. On June 8, 1936, Arnie J. Powers, 42, shot himself to death in his room, having failed to recover his health after coming out from Omaha.

On June 14, 1937 the Trenton hosted its most eloquent suicide, when retired schoolteacher Mrs. Ida Mae Mills, 70, gassed herself with a chloroform-soaked rag alongside an open copy of the book The Right to Die. Her note read, "Remember this–Death should be a smooth finish, not a jagged interruption. There is nothing mysterious nor dramatic about this. Neither was it conceived in a moment of desperation. I think I am as sane as I ever was, but I have long been convinced of the wisdom of mercy killing. Why must I live on, tortured by constant pain, and facing total blindness? My abject apologies to the management for the trouble I am giving them, but I had to have some place to die, didn’t I? I could not vanish into the air."

She could not, but sometime in the early 1960s, it seems, the Trenton Hotel did just that. We can only assume the CRA had a little something to do with that.

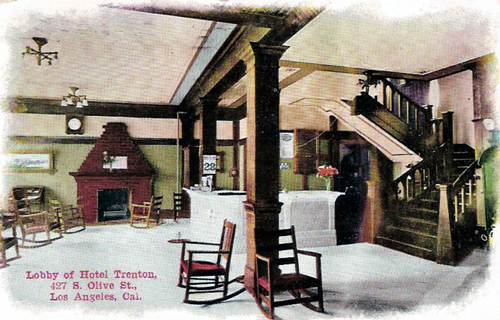

Postcards from the Nathan Marsak Collection, Vasquez and 1908 advertisement from the Los Angeles Times, panoramic photo from the Los Angeles Public Library.

work! In October of 1911, Astoria resident Mrs. W. F. Sapp returned to her room one afternoon to find”¦nothing amiss. But her mother, Mrs. W. W. Loomis, of the adjoining apartment, called attention to having heard her daughter next door at her writing desk while said daughter was supposed to be absent. They opened the locked writing desk”¦to behold”¦gasp! The chatelaine bag, lockets and bracelets and the like were gone, as was the ancestral family tin box (found later in the lavatory, a can opener found on the fifth floor above) once filled with gold watches, fobs, and diamond-set pieces, now scattered to the underworld of crooked, loupe-wearing bangle merchants.

work! In October of 1911, Astoria resident Mrs. W. F. Sapp returned to her room one afternoon to find”¦nothing amiss. But her mother, Mrs. W. W. Loomis, of the adjoining apartment, called attention to having heard her daughter next door at her writing desk while said daughter was supposed to be absent. They opened the locked writing desk”¦to behold”¦gasp! The chatelaine bag, lockets and bracelets and the like were gone, as was the ancestral family tin box (found later in the lavatory, a can opener found on the fifth floor above) once filled with gold watches, fobs, and diamond-set pieces, now scattered to the underworld of crooked, loupe-wearing bangle merchants.

Sunday, April 4, 1937. Little Marguerite made a habit of always coming down to the desk to borrow the Sunday paper. This morning she did not. A concerned John Riley, the elevator operator, put an ear to the Wordens‘ door and ascertained a low moan; he summoned Astoria manager J. E. Harrigan, who, with his trusty stepladder, peered through the transom. After what he saw police arrived in short order and even hardened Detective Lieutenants Ledbetter, Bryan and Lopez, after kicking in the door, had to halt in their tracks at the horror that lay in wait.

Sunday, April 4, 1937. Little Marguerite made a habit of always coming down to the desk to borrow the Sunday paper. This morning she did not. A concerned John Riley, the elevator operator, put an ear to the Wordens‘ door and ascertained a low moan; he summoned Astoria manager J. E. Harrigan, who, with his trusty stepladder, peered through the transom. After what he saw police arrived in short order and even hardened Detective Lieutenants Ledbetter, Bryan and Lopez, after kicking in the door, had to halt in their tracks at the horror that lay in wait.  The Wordens’ attacker or attackers had climbed the Angels Flight stairs and forced entry through the kitchen window just below Olive Street. Shoes were removed before climbing in–traces of sock wool were removed from the plaster casts. (The feet, size eleven.) The assailant is almost certainly responsible for the March 2nd rape and brick-administered basal skull-smashing of

The Wordens’ attacker or attackers had climbed the Angels Flight stairs and forced entry through the kitchen window just below Olive Street. Shoes were removed before climbing in–traces of sock wool were removed from the plaster casts. (The feet, size eleven.) The assailant is almost certainly responsible for the March 2nd rape and brick-administered basal skull-smashing of