As has been noted, when it comes to Bunker Hill, there is no image as iconic as Union Bank Square–the Redevelopment Project‘s first great endeavor–towering over remnants of antiquated Los Angeles. (One could argue there are few sights as telling when it comes to defining Los Angeles in general.) But while we‘re all familiar with those 42 stories of mid-60s glory, who remembers what stood there before? It was that hitherto unsung monument of Los Angeles deco: the Monarch Hotel.

As has been noted, when it comes to Bunker Hill, there is no image as iconic as Union Bank Square–the Redevelopment Project‘s first great endeavor–towering over remnants of antiquated Los Angeles. (One could argue there are few sights as telling when it comes to defining Los Angeles in general.) But while we‘re all familiar with those 42 stories of mid-60s glory, who remembers what stood there before? It was that hitherto unsung monument of Los Angeles deco: the Monarch Hotel.

The Monarch opened in mid-October, 1929. It contained sixty-six hotel rooms, fourteen single apartments, twelve double apartments, a five-room bungalow on the roof, three private roof decks planted rich with shrubbery, and a lobby embellished with hand-decorated ceilings. It was entirely furnished by Barker Brothers with furniture of “modern type and design.”

From the outset, crime dogged the Monarch. Sort of. The first occupants of the bridal suite, in November 1929, were Motorcycle Officer Bricker of Georgia-Street Traffic Investigation and former Miss Losa Pope (the now newly-minted Mrs. Bricker, a purchasing agent at Forest Lawn).

They met when he had arrested her for speeding. On their first morning together as Man and Wife, breakfasting on the roof garden outside their bridal suite, they were mobbed by twenty some-odd members of the Force who decided to burst in and make merry with fellow officer and his tamed scofflaw.

Real crime did, in fact, visit upon the Monarch. (This may have had something to do with opening two weeks before the Crash.) For example:

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

H. N. Willey continued to ply the night clerk trade, and was doing so when two men entered on the early morning of August 31, 1931. When Willey showed them to their room, they pulled out a gun and tried to lock him in the closet. The attempt failed because the door had no outside lock, so the hapless crooks ran downstairs, recovered the $2 they had paid for the room and fled.

H. N. makes the papers again in November of 1931, when on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving Los Angeles is hit by a massive crime wave, in which over a dozen brazen robberies of hotels, groceries, theaters, pedestrians, folks in autos, etc. are shot at and robbed; Willey looks down the barrel of a large-bore automatic and forks over $25.

One thing that‘s nice about the Monarch? It‘s nice to have a bar downstairs. Edgar Lee Smith lived, and drank, at the Monarch.

August 23, 1946. Smith, 51, had been drinking in the Monarch bar but neglected to keep to the cardinal rule of always keeping on the good side of one‘s bartender. This resulted in an after-hours duel that left his bartender, James Donald Chaffee, 28, stabbed to death. When the Radio Officers Hill and Finn found Chaffee‘s body on sidewalk, they went to Smith‘s room, where they found him changing his clothes, and seized a penknife with a one-inch blade.

The fight began when, according to Smith, “Jimmy got sore because I stole his girl.” Smith added that barkeep Chaffee, in retaliation, cut Smith off. Smith, in counter-retaliation, cut Chaffee.

Smith plead guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to one to ten in San Quentin.

Gilbert Carvajal was a 17 year-old Marine stationed at Del Mar, part of Pendleton. He was at the Monarch on May 9, 1957, with his 45 year-old lady-friend Frances Nishperly when it all began. It was 1:15am and he decided it wise to hold up night clerk Frost E. Stacklager (H. N. Willey having retired, apparently) and make off with $22 and jewelry. A few minutes later the two robbed the Trent Hotel of $57.50; despite holding the clerk at knifepoint, the two next fled the Floyd Hotel empty-handed, but snagged $45 from the till at the Auto Club Hotel minutes later. At 23rd and Scarff Sts. the police began shooting into Carvajal‘s car–he tried to make a run for it but was shot down in the street, taking one to the chest. Ms. Nishperly insisted Carvajal had kidnapped her from the corner of Pico Blvd. and Hope St., but police elected to discount this story.

Now, people are forever plunging off the precipices afforded by tall structures (a quick peruse of On Bunker Hill proves that) and that‘s a person‘s right and due. But it‘s different when it‘s an excited doggy.

Buddy was one such excitable pooch, who went nuts and ran right off the top of the Monarch Hotel! Of course the Hand of God intervened, and Buddy–a 2 year-old fox terrier–fell one hundred feet, landing atop an auto roof, but emerged without a scratch, May 1, 1931. (Apparently Buddy had landed on one of the small unbraced portions of the auto top; parking station attendants ran out when they heard a windshield smash and found a confused dog standing on top the machine, looking for a place to descend.)

Buddy‘s daddy, Jimmy Van Scoyoe, was looking frantically for his pooch and had no idea of his aerial adventure when he peered off the roof and saw his Buddy surrounded by a puzzled crowd. Jimmy is reported to have tightly clasped Buddy in his arms and vowed to never let him out of his sight again “even if I have to keep him in bed with me when I go to sleep.” Damn straight!

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the NW corner of First and Rosemont (above, demolished 1962) and another at the NW corner of Sunset and Quintero (still there, vaguely recognizable):

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the NW corner of First and Rosemont (above, demolished 1962) and another at the NW corner of Sunset and Quintero (still there, vaguely recognizable):

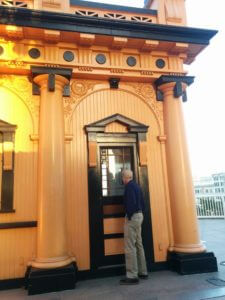

One can also go visit Cramer & Wise’s Van Rensellear Apartments,

SE corner of Franklin and Gramercy”¦  …of course, what they‘re best known for is La Belle Tour.

…of course, what they‘re best known for is La Belle Tour.

Consulting architects on the Monarch were Hillier & Sheet, probably best known for Beverly Blvd. landmark the Dover.

While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929 complex on the NE corner of McCadden and West Leland Way is mysteriously named the Aloha.

While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929 complex on the NE corner of McCadden and West Leland Way is mysteriously named the Aloha.

This 1929 31-unit Mediterranean complex in the Wilshire District still stands:

But this one on El Cerrito was demolished; an 80s building of unusual blandeur has taken its place.

Hillier & Sheet announce this height-limit Norman job will go up at Fountain and Sweetzer; it does not materialize.

S. Charles Lee‘s El Mirador, though, does.

Who loves the lost Monarch? People are quick to fetishize the felled Richfield Tower, and with good reason (I, too, am an ardent obsessive–even owning parts of it); but isn‘t it a bit”¦New York? Doesn‘t it owe a major debt to Hood‘s American Radiator Building? Sure, some might argue that the Streamline Moderne is more natively Angeleno, but not only was that industrial-inspired application an Internationalist movement, but one also feels in its nautical element a particular evocation of our neighbor to the north, San Francisco.

What is elementally endemic to the land, here, is the Ziggurat Moderne of the Monarch Hotel–that there is something in the setback style that elicits a feeling for the indigenous, the “really” American, in that the mock-Mayan comes closest to the true architecture of this part of the world. The core of this argument comes, of course, from Francisco Mujica‘s 1929 History of the Skyscraper, where he hints at just that–that pre-Columbian pyramids are the correct expression of modernity, and vice versa (hence the natural evolution of the 1916 New York setback laws”¦glorious mother of what Koolhaas termed the Ferrissian Void).

Thus–where one might see the Monarch as somewhat squat:

…we should take that as monumentality in its most impressive (if not oppressive, if that‘s what reverberates in your Incan blood) form.

1906, the NW corner of Fifth and Figueroa at bottom right:

1950, twenty years after the installation of the Monarch:

1953, with the addition of the Harbor Freeway:

After fifteen years of Sturm n Drang, on February 3, 1964, the $350 million Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project got its first bite–Connecticut General Life offered $3.3 million for the block-square site that housed the Monarch Hotel.

CRA Chairman William T. Sesnon Jr., expressed his elation: “The sale is virtually completed. We are overjoyed by this development. It‘s our hope it will serve as the real kickoff for the entire Bunker Hill project.”

Thirty days later–March 4, 1964:

On March 30, 1965, red-jacketed attendants ushered dignitaries under a white-fringed canopy, where they watched a bulldozer tear up some concrete. “Welcome to Bunker Hill–at last,” proclaimed Sesnon. “This is the start of something dramatic.”

Some of the luster of Sesnon‘s kickoff was dulled when in 1966–with the Union Bank half built–City Administrative Officer C. Erwin Piper and his staff issued a scathing report on the CRA. It sited faulty operational control, an absence of clear-cut policies and poor internal coordination, at terrific taxpayer expense. By the end of 1967 no more land had been disposed of, the CRA had lost half its department heads, had no executive director, and Sesnon had been replaced by Z. Wayne Griffin.

The Battle of Bunker Hill would continue to be waged–that long, slow, protracted engagement, which like its previous fifteen years, would need another fifteen years before things shifted into high gear again.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; opening Monarch shot (1930), Mott-Merge Collection, California State Library, and back of Monarch shot across Fremont St., Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library

When it rains, it pours. Which is probably a good thing, since rain will put out all that pesky fire.

When it rains, it pours. Which is probably a good thing, since rain will put out all that pesky fire.

Remarkably, the Savoy still stands. The 600-car Mutual at left in the image above is now the foundation for

Remarkably, the Savoy still stands. The 600-car Mutual at left in the image above is now the foundation for

In November 1979, the Times ran a piece about Angelus Plaza, Bunker Hill’s subsidized housing project for seniors. For the article they dug up one of the original uprooted persons, a Jim Dorr, 73, who‘d been sent a notice by the CRA to vacate the Stanley Apartments on November 15, 1965. He‘s glad he saved those displacement papers all these years: HUD will give him priority in the otherwise random lottery.

In November 1979, the Times ran a piece about Angelus Plaza, Bunker Hill’s subsidized housing project for seniors. For the article they dug up one of the original uprooted persons, a Jim Dorr, 73, who‘d been sent a notice by the CRA to vacate the Stanley Apartments on November 15, 1965. He‘s glad he saved those displacement papers all these years: HUD will give him priority in the otherwise random lottery.

As has been

As has been

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the

…of course, what they‘re best known for is

…of course, what they‘re best known for is  While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929

While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929

During the 12 years that the Bunker Hill Playground served the neighborhood, its facilities were tremendously popular, and its programs well-attended. However, it wouldn’t last long. In 1962, the Department of Parks and Recreation recommended sale of the playground and recreation center to the CRA for $325,000. Within a year, the City Council would approve the sale, cash the check, and soon, the playground was just another Bunker Hill ghost.

During the 12 years that the Bunker Hill Playground served the neighborhood, its facilities were tremendously popular, and its programs well-attended. However, it wouldn’t last long. In 1962, the Department of Parks and Recreation recommended sale of the playground and recreation center to the CRA for $325,000. Within a year, the City Council would approve the sale, cash the check, and soon, the playground was just another Bunker Hill ghost.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock. But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

father, William Howard, later reported that he’d left a very intoxicated Lucille and his daughter alone in a car while he made a phone call. When he returned, the car was missing, as were Lucille and Gloria.

father, William Howard, later reported that he’d left a very intoxicated Lucille and his daughter alone in a car while he made a phone call. When he returned, the car was missing, as were Lucille and Gloria.

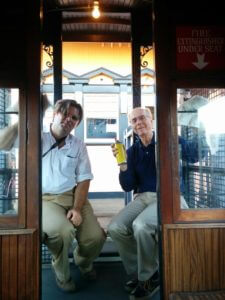

“Up there‘s Bunker Hill, folks, and what a pain it was to shlep from your gracious home down to the Grand Central Market below, there, behind you. But then came riding up lawyer, engineer, friend of Lincoln, Colonel James Ward Eddy, who was sixty-nine when he convinced the city that it needed a funicular in the 3rd street right-of-way between Hill and Olive. Eddy built ”˜The Los Angeles Incline Railway,‘ known to all and sundry as Angels Flight, no apostrophe thank you, complete with a hundred-foot observation tower that housed a camera obscura. Mayor Snyder made the inaugural 45-second journey on January 1, 1902. The cars were biblically named ”˜Olivet‘ and ”˜Sinai‘ and were painted a saintly white, though later orange and red, and a trip up the 325 feet of 33% grade was originally a penny, though they jacked that up to a nickel. What‘s with the BPOE arch, you ask? Did the Benevolent Protective Order of Elk have a hand in all this? Not really. A hundred years ago the Elk’d go nuts during ‘Elk Week’ and spend lavish sums all over the city with fireworks and

“Up there‘s Bunker Hill, folks, and what a pain it was to shlep from your gracious home down to the Grand Central Market below, there, behind you. But then came riding up lawyer, engineer, friend of Lincoln, Colonel James Ward Eddy, who was sixty-nine when he convinced the city that it needed a funicular in the 3rd street right-of-way between Hill and Olive. Eddy built ”˜The Los Angeles Incline Railway,‘ known to all and sundry as Angels Flight, no apostrophe thank you, complete with a hundred-foot observation tower that housed a camera obscura. Mayor Snyder made the inaugural 45-second journey on January 1, 1902. The cars were biblically named ”˜Olivet‘ and ”˜Sinai‘ and were painted a saintly white, though later orange and red, and a trip up the 325 feet of 33% grade was originally a penny, though they jacked that up to a nickel. What‘s with the BPOE arch, you ask? Did the Benevolent Protective Order of Elk have a hand in all this? Not really. A hundred years ago the Elk’d go nuts during ‘Elk Week’ and spend lavish sums all over the city with fireworks and  carnivals and since their lodge replaced the Crocker mansion at the top of Angels Flight in September 1908, they elected to donate this swell gate here around 1909. The BPOE lettering on the arch was actually covered up for many decades when the building above became a Moose lodge in 1926. Anyway, as the city moved west, the gingerbread private homes of the 1890s were cut up into rooming houses, and Bunker Hill took on all that charm we now call shabby chic. In 1950, large insurance companies, the Building Owners and Managers Association, and the Community Redevelopment Association proposed the razing of Bunker Hill to develop 10,000 rental units. In 1959 the City Council declared Bunker Hill blighted, a slum to be cleared and redeveloped. The Elks Lodge/Moose Lodge gets wiped away in 1962. In 1969 Angels Flight was finally removed and stored, with a promise to return it shortly. It was reinstalled here, half a block down, a mere twenty-seven years later, though a tragic accident in 2001 has closed it temporarily.”

carnivals and since their lodge replaced the Crocker mansion at the top of Angels Flight in September 1908, they elected to donate this swell gate here around 1909. The BPOE lettering on the arch was actually covered up for many decades when the building above became a Moose lodge in 1926. Anyway, as the city moved west, the gingerbread private homes of the 1890s were cut up into rooming houses, and Bunker Hill took on all that charm we now call shabby chic. In 1950, large insurance companies, the Building Owners and Managers Association, and the Community Redevelopment Association proposed the razing of Bunker Hill to develop 10,000 rental units. In 1959 the City Council declared Bunker Hill blighted, a slum to be cleared and redeveloped. The Elks Lodge/Moose Lodge gets wiped away in 1962. In 1969 Angels Flight was finally removed and stored, with a promise to return it shortly. It was reinstalled here, half a block down, a mere twenty-seven years later, though a tragic accident in 2001 has closed it temporarily.”

hoist busted, sending Sinai plummeting down the incline. The worst injury was actually a Mrs. Hostetter (of the

hoist busted, sending Sinai plummeting down the incline. The worst injury was actually a Mrs. Hostetter (of the

hired an entity absurdly ill-suited to the task of restoring Angels Flight: Lift Engineering. Lift Engineering built ski lifts. Ski lifts that

hired an entity absurdly ill-suited to the task of restoring Angels Flight: Lift Engineering. Lift Engineering built ski lifts. Ski lifts that

Certainly many breathed a sigh of relief. Gone was that clattering anachronism, garbed in the orange and black of an Edwardian Hallowe‘en, which could no longer connect the downmarket quaffers of cheap chop suey with the newly ensconced deadbolted seniors and senior bankers and the like.

Certainly many breathed a sigh of relief. Gone was that clattering anachronism, garbed in the orange and black of an Edwardian Hallowe‘en, which could no longer connect the downmarket quaffers of cheap chop suey with the newly ensconced deadbolted seniors and senior bankers and the like.