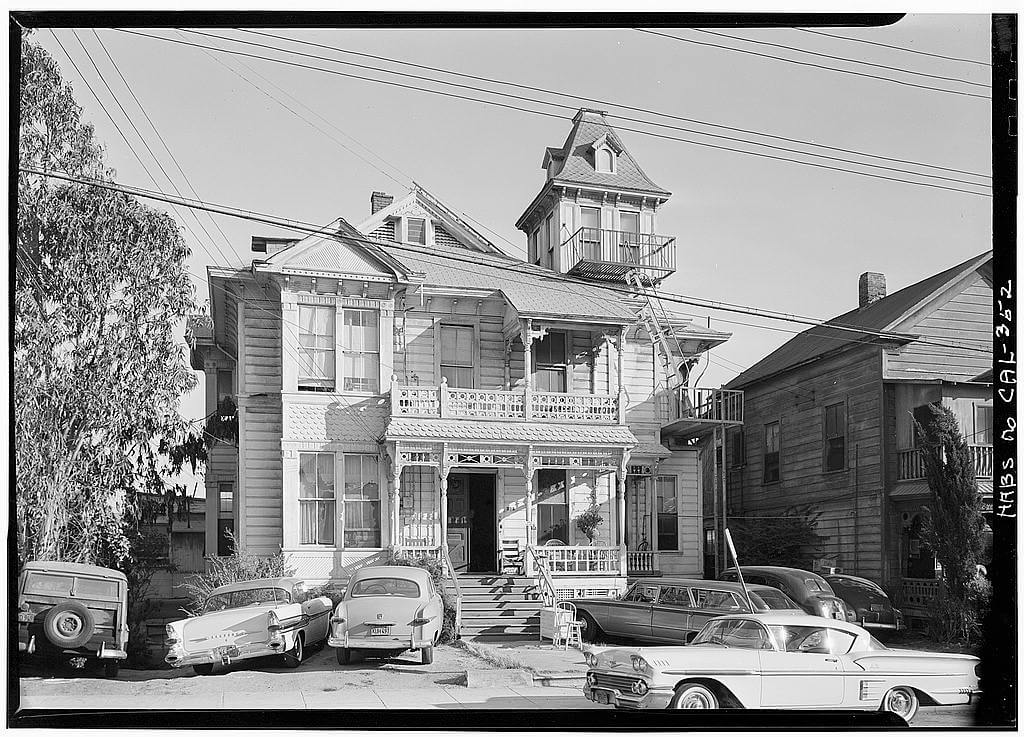

Bunker Hill Avenue was probably the most picturesque street in the neighborhood of the same name. The avenue was much more narrow than the other streets and was lined with some of the most impressive mansions on the Hill. Compared to most of its neighbors, the house that stood at 339 South Bunker Hill was farily modest and came to be affectionately known as the Salt Box. Despite being considerably less grand than the other Victorian beauties on the street, the Salt Box was saved from the wrecking ball and moved to a new location to stand as a tangible monument of the rapidly vanishing community. Unfortunately, the charming structure that stood for eighty years on its original location, only lasted a few months at its new home.

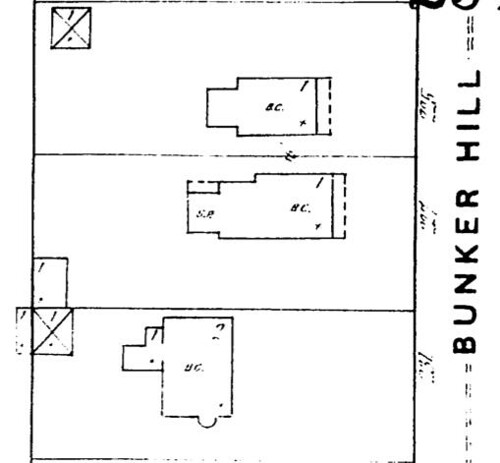

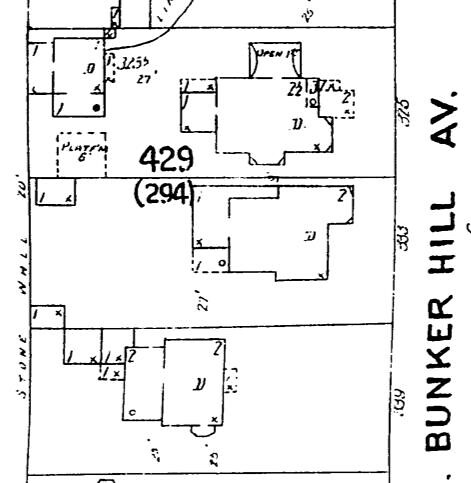

The Salt Box was built on Lot 14, Block L of the Mott Tract, which was two doors down from a grand mansion that came to be known as the Castle. The 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps shows the two buildings as being constructed, as well as the residence between them. Since Rueben M. Baker owned the lots, he was probably responsible for the construction of all three houses. Baker resided at the Castle until 1894 and possibly rented out the Salt Box until selling it to Ada Frances Weyse and her husband Rudolph in 1892.

The Weyses also rented out the Salt Box, which appeared to have been converted into a muti-resident boarding house as early as 1891,with rooms constantly being advertised in the classifieds. Joseph L. Murphey and his wife, Augusta, purchased the home in 1902, but it is unclear if they lived in the house or merely took over landlord duties.

In 1900, the house at 330 S Bunker Hill was home to two households. By 1910, the Salt Box had been divided up into seven separate units which housed families as well as single tenants. In 1920 there were ten units and by 1939 the house had been further divided into thirteen separate residences. Those who called the Salt Box their home came from all walks of life and included painters, nurses, waiters, and of course pensioners who could afford rents that were as little as $9.75 per month.

Compared to the shenanigans taking place at other boarding houses on Bunker Hill, the Salt Box had a rather serene existence. With the exception of resident Annie Prendergast, who was hit by a car at the corner of 4th and Grand and killed, the residents of the Salt Box lived quiet lives, until the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) came knocking.

By 1968, all of the once proud Victorians of Bunker Hill Avenue had been demolished, except for the Castle and the Salt Box. The two structures that had been constructed at the same time had been spared. Once the CRA began pushing forward with their grand redevelopment plan in the mid-1950s, the writing was on the wall for the mansions in the neighborhood, and in an attempt to save a couple of the structures, the Salt Box was declared Historic Cultural Monument #5 in October in August 1962. Designation was soon bestowed upon the Castle which became HCM #27 in May 1964. The rest of the decade was spent trying to figure out a way to spare the two structures from the wrecking ball.

At the end of 1968, the decision was finally reached to move the Castle and Salt Box to Highland Park in an area called Heritage Square. The pair of structures were relocated to their new home in March of 1969 and awaited restoration. These grand plans for the faded beauties were never realized because in October of 1969, vandals torched both houses and eighty years of history were wiped out in a matter of minutes.

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.