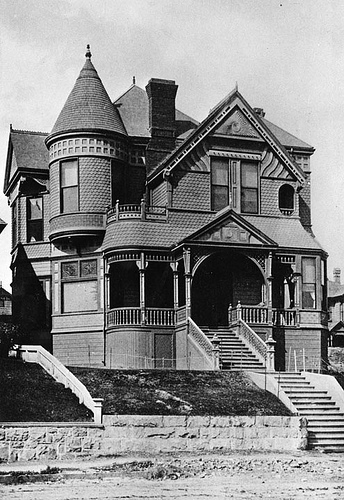

Before the Community Redevelopment Association swung its scythe across Bunker Hill, one building tried to do itself in. This structure was by all evidence a living, cursed thing, and like the House of Usher disappearing into the tarn, it acted to remove itself from this world. Shades of the Overlook Hotel–someone or something used the old exploding boiler trick to force this assembly of apartments from its supramortal coil.

I speak of the Hotel Central, aka the Clayton Apartments, aka the Lorraine Hotel. Change the names all you want, there‘s something wrong at 310 Clay Street. Kim‘s numerous posts about the place attest to that.

The spot was a trouble magnet even before the hotel‘s erection. Back when 310 was a double dwelling, it attracted kerchief-weilding lady-gagging burglars.

By 1910 the Hotel Lorraine stands on the site and Jerome Hite elects to shoot his wife in the neck.

Come 1914, proprietor-of-the-place Claude Mathewson–gets, what, tired of watching the walls bleed? listening to the screaming faces jutting from the washbasin mirror?–elects to pop two new holes into his lovely wife and one into his own head.

Shortly after, in that room where try as one might the blood just never quite washes out, a real estate titan is taken down for sordidness.

A year later, the establishment, now named the Clayton, has become a veritable den of iniquity. The new proprietor is a Mrs. Florence Cheney. According to her, the property is owned by Leon Levy, “about whom no one concerned could give any information.”

Mrs. Cheney shows up again as a witness in the 1916 Percy Tugwell trial; Percy robbed and murdered Senator‘s-daughter Maud Kennedy, and while Mrs. Cheney asserted that Maud may have committed suicide because she was being threatened by boxer Louis “Cyclone Thompson” Astosky, her character and thus credibility were attacked mercilessly.

Leon Levy decides to get out of the 310 Clay business after changing its name again to the Hotel Central.

Things stay quiet at 310 Clay for the next couple decades or so…acts of ill fortune befall its residents elsewhere.

In 1922, for example, Frank Macey, son of a wealthy Phoenix shoe dealer, dropped from sight for a week after staying in the Central. He ended up as a nameless bloody pulp in County Hospital, hovering in and out of consciousness, until at last identified as the prodigal Frank.

In 1923, Sander Serrano, 22 year-old graduate of USC, was playing pool at 155 East First when he was accused of jostling another player. For this he nearly lost his arm to his penknife-wielding opponent, who severed a slew of arteries and stabbed him in the throat.

A 1936 beer parlor fight at 121 South Main resulted in the stabbing of Hotel Central resident Walter Paine.

And so it goes, until the hotel could take no more, or had claimed enough souls, or something otherwise unknowable to mere man.

Mid-day, November 27, 1953. O. B. Reeder, a 73 year-old retired printer, was bent over a table preparing Christmas gifts for mailing. Houses of Hell hating the Christmas season and all, the boiler exploded in rage, sending Reeder‘s door across the room and into his back. Directly across the hall, from where resident Gus Poulas‘ guardian angel had guided him elsewhere, the room was completely wrecked, all tumbled furniture and great cakes of plaster torn from the walls.

The boiler room itself was obliterated into a mass of twisted metal and piles of timber and concrete wall blocks. Plaster from walls and ceilings was concussed to floors throughout the hotel. The windows and doors in the first three floors were cracked or blown out by the explosion, which attracted a large lunchtime crowd of spectators to the Hill Street section of the Grand Central Market. (The back of the hotel towered over a Hill St. parking lot:)

Making the incident all the eerier is owner/manager William Ogawa‘s statement that while the boilers were under repair, he was certain that gas to the boiler room had been turned off when the boilers went out of order several days previous.

In any event, everything was rebuilt, doors rehung, windows reglazed. Less than a decade later the scythe swung and all that was 310 Clay was at the bottom of a landfill, the CRA accomplishing what the Lorraine/Clayton/Central couldn‘t do itself.

But remember what I said about the spot being a trouble magnet even before the hotel‘s erection? Is there some sort of Poltergeist-style burial-ground whatnot at work here? Flash forward a hundred years from our tale of the simple double residence.

310 Clay at lucky number 13:

The site of 310 on the Ghost Street that is Clay:

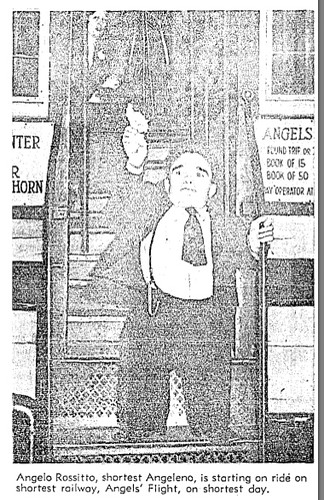

On that very spot. February 1, 2001. What spanner of the underworld was tossed into the heavenly works of a newly-located Angels Flight?

This is the ground zero of Clay Street. Clay Street, the street that had to be destroyed. The street whose very name–clay–symbolizes (via Nebuchadnezzar’s dream) the division of an empire, and the end of a kingdom.

Hotel Cental photographs courtesy Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library

Newpaper images from the Los Angeles Times

A building permit for a 3-story brick lodging house that would become the Saratoga Hotel was issued to W.W. Paden and Louis Nordlinger in the summer of 1914. A year later, the hotel was offered for sale, exchange, or lease, offering "long lease, good furniture, and cheap rent."

A building permit for a 3-story brick lodging house that would become the Saratoga Hotel was issued to W.W. Paden and Louis Nordlinger in the summer of 1914. A year later, the hotel was offered for sale, exchange, or lease, offering "long lease, good furniture, and cheap rent."