In 1905, when George Santayana wrote, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it," we can be quite certain that he was not sitting in an east-facing room of the Biltmore Hotel, looking out over Pershing Square. That’s because the hotel didn’t exist yet, and L.A.’s old public square was still called Central Park.

But the philosophers’ words seem very apt as we reflect on the oddly familiar reports coming out of Pershing Square, City Hall and the press this week.

If you want to know what’s happening in 2012, it’s easy enough to follow that trail”¦ bearing in mind that business groups that are able to pay lobbyists and publicists and who donate to politicians always have an edge when it comes to getting their perspectives heard. (An alternative view is here.)

Los Angeles Times, October 31, 1931

Here On Bunker Hill, we’d rather cast an eye backwards, in hopes that by reminding the players in our modern comedy of the old roles they are inhabiting, that their performances will be more thoughtful and humane.

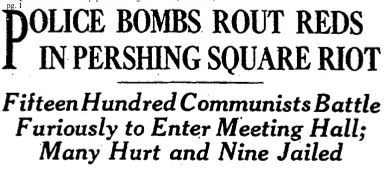

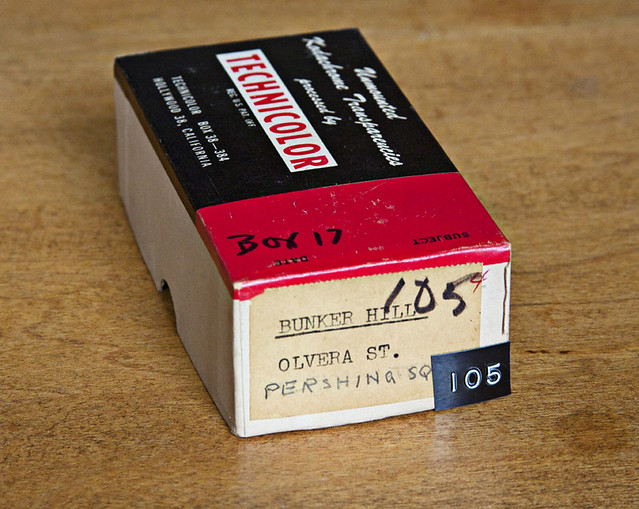

Behold, Pershing Square in the middle 1950s! This north-facing photograph, shot in 3-D Technicolor by the celebrated vaudeville dancer (and chronicler of Bunker Hill) George Mann, has not been seen in nearly fifty years. It is one of four vintage images of the park just discovered in Mann’s archive, and scanned especially for inclusion in this blog post by Dianne Woods.

photo: George Mann

Here we see the plain and grassy park as it was remade, following the controversial construction of an underground parking lot and civil defense shelter. Gone are the beloved walkways and mature tree cover that were for decades the symbols of the place, and cause for concern by moralists who raved that the bushes were filled with libertines and the shady spots with loudmouthed loons. Fine old trees have been replaced by fast-growing bamboo and a few anemic rose bushes.

Compared to the old Pershing Square, this park is a dump.

Pershing Square as it was

And yet, along the semi-shaded benches that line the lawn, many dozens of people have gathered in the heat of the day–so many that some must stand, or venture out onto the lawn to sit on low walls in full sun.

photo: George Mann (detail)]

Although the park’s designers sought through the redesign to make the space less hospitable for loitering, the urge of the people to come together in the commons proved stronger than the grim psychological landscape.

We see that it is a multi-racial crowd, mainly men, nearly all middle-aged or elderly. Among them must be a number of the 9000 denizens of single rooms up on Bunker Hill, the voiceless many who will in just a few years be cast to the winds after the largest eminent domain action in US history.

photo: George Mann

Over in the northeast corner, a young black man in a natty brown sport coat seems to be taking advantage of the crowd’s idle attentions to practice his oration. Just behind, elevated on a box, a fellow all in white gestures meaningfully to a man who looks interested, if perhaps a little bit afraid.

photo: George Mann (detail)

This area was our speaker’s corner, much like the famous one in Hyde Park, London, a loud, strange, loathed and beloved zone of free expression (and gleeful heckling) that was over the decades subject to repeated suppression attempts by business groups and politicians. The names of these powerful entities may be different, but their complaints and tactics have scarcely changed in six decades.

letter to the editor, Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1953

The problem then as now, of course, was that after being instructed crack down on "undesirable" behavior within the park’s borders, the unsubtle mind of a beat cop was pressed to its limits by the appearance of such unusual public activity as the impromptu June 1955 attempt by fifteen young classical musicians to perform Handel’s "Water Music" beside the park’s fountain.

It was weird, it was different–of course it must be against the rules.

"Not on my beat! No permit, no music!" exclaimed Patrolman Bill Shirley, headless of the cries from the people of the park to just let the kids play. Once the Young Artists Chamber Orchestra had been shooed away, a reporter watched as a group of Bunker Hill regulars sang along to a hymn played on guitar and concertina. Officer Shirley had no complaint, for this was a daily feature of park life.

Similarly, in August 2012 when a group of chalk artists came from Oakland, at their own expense, to create a sidewalk mural during the Downtown Art Walk, they were harassed by police and private security guards, the media and blogosphere fretted that they might be planning violence, and one of the artists was arrested.

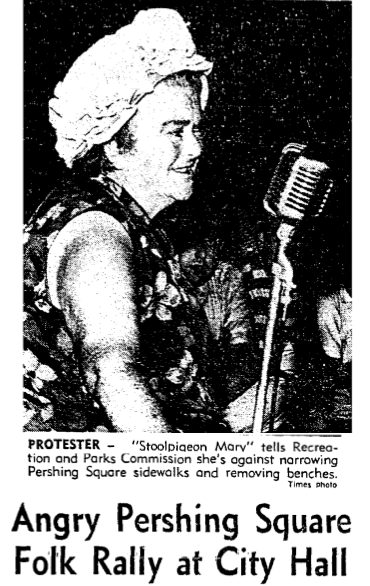

But let’s get back to Pershing Square history. Like September 1963,when a colorful group of about forty Pershing Square habitués including one "Stoolpigeon Mary" protested plans by the Rec and Parks Department to further diminish the already compromised layout of the park, removing the few trees and benches and narrowing the pathways.

This $100,000 proposal, financed by parking revenues, was loudly denounced as an attack of the "rich against the poor." The ragged citizens marched together to City Hall to decry these actions of the wealthy, those lucky ones who had air-conditioned offices, luxurious homes and private clubs at their disposal, and yet seemed so intent on taking away the one place where the poor of downtown could escape their hot single rooms and enjoy each others’ company in a natural setting.

Photo: Los Angeles Times

And indeed, the main proponents of the 1963 "beautification" plan–one misstep of many towards the hideous concrete hell that is today’s Pershing Square–were the Downtown Business Men’s Association (known now as the Central City Association) and Mayor Sam Yorty, who would later be voted among the worst three big city leaders in American history. Mayor Yorty expressed concern in particular that the park had become a haven for "undesirables" who frightened females.

The truth was that there were unafraid women to be found in Pershing Square, but never so many as the men. But we know of them from accounts of how they preached or sang the gospel, or cared for the birds like the much-loved retired telephone operator Pigeon Goldie Osgood (whose 1964 murder in the Cecil Hotel was never solved). George Mann’s newly rediscovered photograph suggests that the ladies preferred the shady, less crowded corners of the square.

photo: George Mann

The last Pershing Square photo in the set shows the scene looking west towards the Biltmore Hotel from near the corner of Sixth and Hill, not far from where the Occupy LA protest group holds its thrice-weekly general assemblies today.

photo: George Mann

The path is shady, and an old man bends to drink from the water fountain. A woman, perhaps holding a petition, has engaged a seated man in earnest conversation.

photo: George Mann (detail)

Beside the tall statue of the doughboy on his plinth, we see a man whose body language evokes the classical portrayal of melancholy.

photo: George Mann (detail)

There’s something beautiful in his solitary desperation, a formal elegance in the body’s compact lines–and also a sense of hope because, as lonesome and pained as this individual appears, he still was able to take his place in the lively public park with all the other souls of the city, not shooed or hidden away as an undesirable, but there on the wall as a member of a community. The park was there to accept all comers, to give them a safe place to rest, cool water, human company and a breeze off the fountain.

Such are the vibrant scenes that emerge from a box tucked away many decades ago by a tall, funny man who went out into his native city looking for images that would resonate as uniquely of Los Angeles. He went, of course, to Pershing Square, and to Bunker Hill, and to the Plaza and Olvera Street. Of the three, Bunker Hill is gone forever, the Plaza is a tourist attraction and still a place for the people to gather, and Pershing Square is in terrible peril.

Pershing Square is today far, far worse than the 1950s redesign, or the 1960s one, or the 1980s one. With each change, the park has become less accessible, more restrictive, less green, less vibrant. This is a place where it takes longer to read the rules of what is not allowed than to walk right into the park and out again.

If "Stoolpigeon Mary" and her friends could see what’s been done to Pershing Square since they marched to City Hall in 1963, they would be horrified–but probably not surprised. For the current iteration of the park–a sprawling hardscape broken up by confusing walls and a rarely-functioning, nearly-waterless fountain, historic figures relegated to a Sculpture Ghetto that doubles as a dog run, the small patch of grass roped off, the benches deliberately divided to deter anyone from even thinking about lying down–is a space designed by the wrong people for the wrong reasons.

Esotouric tour guide Richard Schave explains the problems

So why is Pershing Square so awful?

Fear and money, two powerful forces that don’t belong anywhere near a public park. Money came to the park in the form of the city-owned underground parking lot, for which the old trees and paths and fountain were ripped up in 1951, in the first assault upon its heart.

Fear came to the park in the form of a civil defense shelter, hidden away within the garage, and later in attempts to legislate and design away the park’s appeal to undesirable Angelenos: communists, homosexuals, the poor, the mad, the homeless, the old, the revolutionary, the anti-social, the voiceless.

Fear and money are good for politicians, but very bad for public policy and public space. Try to imagine any one of the great parks of the world, forced to bend to these two incompatible motivations. Imagine the lawns of Central Park, roped off so nobody can rest on them. Or the Serpentine pond in London, drained down to the rocks. Or Griffith Park, its paths covered over in concrete, its trees cut back to eliminate the shade.

Fear is no way to design a city.

It is not too late for Pershing Square to again be a great public space, but it’s going to require great courage by our civic leaders to reject false and alarming narratives of "decadent" misbehavior and harm to phantom businesses, and to stand up for the precepts on which America was founded. And it will require that our people involve themselves is a space that defies involvement, and demand something better for themselves and for people not at all like them.

Let these beautiful and powerful images, sent across the decades from the eye of the great George Mann, give us all a star to steer by. Let’s not be afraid of one another or of how our fellow citizens might behave. Let us instead make a fine place in which to be fine people, and see what surprises await us there.

*

If you would like to be involved in the development of a more humane and inspiring Pershing Square, please join the Pershing Square People Improvement District.

–Kim Cooper, editrix, On Bunker Hill

One thought on “Looking Backward: Depopulating Pershing Square, 2012-1954”

Comments are closed.