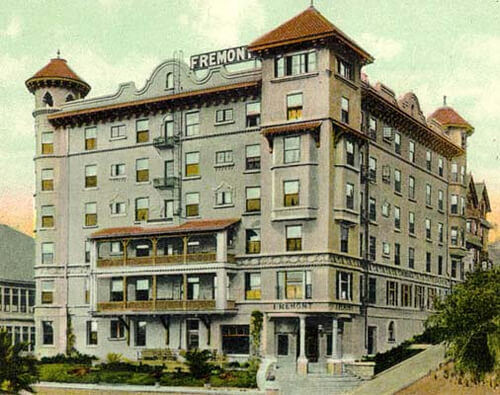

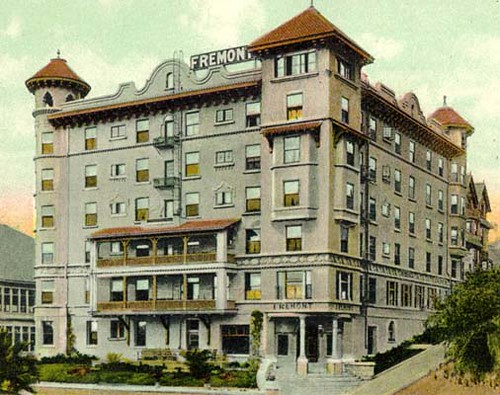

The Belmont was a behemoth at the base of Bunker Hill, its situation on the southern center beckoned folk who–were we to paint in purely lurid hue–simply sought a thieves den, or that final refuge before the big self-snuff. Was there more to this big, beautiful building? Why, naturally.

It all began with the YWCA, an organization that sought to harbor white Christian women from the williwaws of urban iniquity. And where better to do so than that hillock of high-mindedness, Bunker Hill?

A colony of civic-minded women formed the LA-YWCA in 1893 in two rooms at 212 S. Broadway, then moved into the Schumacher Building at 107 S. Spring in 1894. They then shuttled off into the shelter of the old City Hall at 211 W. Second, and finally took over a whole floor of the Conservative Life building at the NE corner of Third and Hill in ‘06. They were renting out a small building as their annex, on the same side of Hill, forty feet north of Third, and decided enough of this penny-ante gynoprotection, we‘re purchasing that property and erecting an sky-scraping HQ.

They dropped cornerstone in 1907 and moved in aught-eight. Its basement held an auditorium for 500, a gymnasium, and a 30×50‘ swimming pool. It was most noted for its gargantuan light well, which formed an open-air patio famous for its flower boxes filled with color-coordinated flora cascading to a fancy tile floor.

4,000 women, including 1,600 students engaged in the study of the domestic sciences, swam and ate and sewed and so on and all was fine and good until 1919, when the Y gals sold the building, deciding “to be nearer the shopping.”

(In 1926 they opened their grand Y-hotel at 939 S. Figueroa, moving their offices into this building on the right [now the site of the Hotel Figueroa‘s pool].)

251 South Hill was purchased by the Union League Club of Los Angeles, where the Republican Women‘s Club (the incipient CFRW). often met.

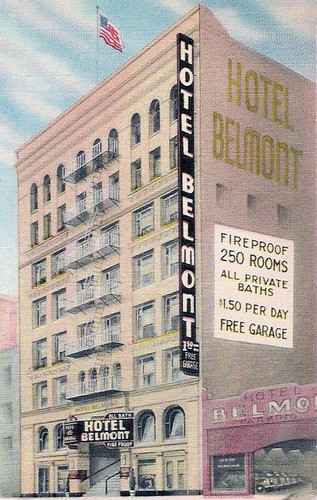

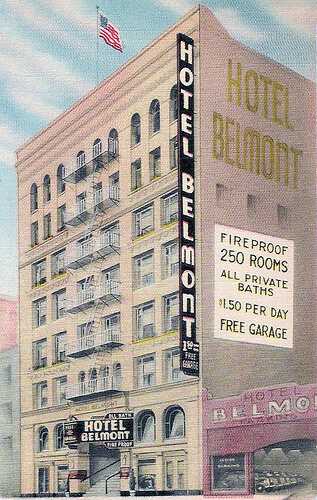

The Union League held on to 251 until 1924; its conversion into the Hotel Belmont begins in April of that year. Alexander Mayer spends $400,000 ($4,812,791 USD2007) in the remodel–remaking 200 rooms, all with shower and bath, all with hand-painted furniture.

One of the Belmont‘s most notorious residents was Santa Claus. Motley Flint, Los Angeles Postmaster and Illustrious Potentate of the city‘s Al Malaikah Temple (our local Shriners, AAONMS), arranged with postal authorities to have all letters addressed to Santa (which theretofore had gone to the dead-letter office) sent to the Belmont Hotel, as that was where the Shrine set up their annual Christmas relief drive. The basement would fill with donated toys, clothing and fruit cakes; everyone could come and receive yuletide relief at the Belmont. And the Shriners special Santa squad found each and every letter-penning tot and saw to it that the hoped-for toy made it from the Belmont basement into their needy hands.

Another fun member of the Belmont clan was Walter Maloof, 55, a familiar sight among the Downtown shuffling class, a gent who spent his days peddling watches and other odd articles on street-corners. Apparently there‘s good money in the odd article, as after he died in his Belmont hotel room in February 1963, his bankbook showed he had some $19,000 ($127,399 USD2007) squirreled away.

Of course, the Belmont also harbored the likes of Achilles N. Bororas, 41, whose not only knocked over markets and service stations up and down California in 1954, but robbed churches and nabbed narcotics from drugstores.

You don‘t mess with the Belmont when it comes to committing crimes. James Rader, 28, led a gang of hotel robbers. His accomplices were Gordon Edwards, 18; Frank Darrow, 22; Miss Margie Petrie, 18; and a sixteen year-old girl. They‘d knocked over fifteen downtown hotels when they thought they‘d take on the Belmont, March 9, 1957. The gang were in mid-rob when Edwards was clobbered by 71 year-old Belmont  elevator operator William Patterson, who struck Edwards with his stool (that is, the small stool he sat on in his elevator) and knocked the knife from his hand. Rader struck Patterson with the butt of his gun; the robbers then tangled with 65 year-old Belmont desk clerk A. B. Cramer and eventually fled the scene empty handed–even more so than they came in with, as one of the crew lost their wallet, and they were all easily traced to a downtown roominghouse and arrested.

elevator operator William Patterson, who struck Edwards with his stool (that is, the small stool he sat on in his elevator) and knocked the knife from his hand. Rader struck Patterson with the butt of his gun; the robbers then tangled with 65 year-old Belmont desk clerk A. B. Cramer and eventually fled the scene empty handed–even more so than they came in with, as one of the crew lost their wallet, and they were all easily traced to a downtown roominghouse and arrested.

And there are always those who seek permanent solutions to temporary problems. They, as such, instead of waiting for God to fire them, will raise their fists to the heavens and yell “I quit!”

On March 29, 1936, employees of the Belmont were alarmed that Jeanette Stevenson, 45, wouldn‘t answer her telephone. The note she left described domestic difficulties; she‘d decided a bottle of poison was the antidote to that particular issue.

In January 1938, Mrs. Veronica De Shon Miller, 47, recently of Kansas City, divorced, despondent over the death of a friend, and an out-of-work beautician to boot, soaked a towel in ether and smothered herself in her Belmont flat. She was saved there by a friend. Fearing that the Belmont was conspiring to keep her alive, she left a note regarding the disposition of her belongings and made her way to the building at Fourth and Broadway where she once operated a beauty parlor, and flung herself to the concrete floor at the bottom of the light well.

In January 1938, Mrs. Veronica De Shon Miller, 47, recently of Kansas City, divorced, despondent over the death of a friend, and an out-of-work beautician to boot, soaked a towel in ether and smothered herself in her Belmont flat. She was saved there by a friend. Fearing that the Belmont was conspiring to keep her alive, she left a note regarding the disposition of her belongings and made her way to the building at Fourth and Broadway where she once operated a beauty parlor, and flung herself to the concrete floor at the bottom of the light well.

September 28, 1942. Dr. Robert E. Hunsaker, 45, was due in court to face a hearing in a suit filed by his third wife for divorce. So he got a room at the Belmont. Top floor. Desk clerk Bernardo Sargil noticed Hunsaker on the window ledge and called the cops; when they got there they found dancer Ruth Rex in his room, pleading with him not to jump. The cops tried to grab him but Hunsaker ordered them back; finally he said “So long boys, this is getting tiresome,” and loosened his grip, falling the length of the building to meet Hill Street below.

September 28, 1942. Dr. Robert E. Hunsaker, 45, was due in court to face a hearing in a suit filed by his third wife for divorce. So he got a room at the Belmont. Top floor. Desk clerk Bernardo Sargil noticed Hunsaker on the window ledge and called the cops; when they got there they found dancer Ruth Rex in his room, pleading with him not to jump. The cops tried to grab him but Hunsaker ordered them back; finally he said “So long boys, this is getting tiresome,” and loosened his grip, falling the length of the building to meet Hill Street below.

November 1, 1942. Anne Kennedy, 18, was despondent over ill health, or so letters left in her Belmont hotel room indicated. Nevertheless she was still gaily dressed in her black-and-yellow Halloween party costume when she leapt, or fell, from her sixth-floor window at the back of the hotel.

Third and Hill, 1906, pre-YWCA: Angels Flight “inclined cable tramway” at far left; the St. Helena Sanitarium (perhaps you‘ve noticed the “Vegeterian Café” signage in images of Angels Flight?–that‘s these folk); and some residential structures at 251 and beyond (including one labeled “old & vacant”). The shingled structure in the vintage image above (that‘s a “Berlin Dry Cleaning” truck in front), seen below as 247, was the Kensington. Above, the Astoria.

1950: Behold, the 1907 YWCA, though it‘s been the Belmont now for twenty-five-some years. St. Helena‘s was redubbed “My Hotel” and has a liquor store in its corner. The structures to the east have been wiped for parking; the Kensington is now the Belmont garage. Above, the Astoria has a neighbor, the 1916 Blackstone Apartments.

1950: Behold, the 1907 YWCA, though it‘s been the Belmont now for twenty-five-some years. St. Helena‘s was redubbed “My Hotel” and has a liquor store in its corner. The structures to the east have been wiped for parking; the Kensington is now the Belmont garage. Above, the Astoria has a neighbor, the 1916 Blackstone Apartments.

A close-up from an image in last week‘s post. A glimpse of Angels Flight heading down to the corner of Third and Hill. There‘s the Belmont and her giant light well. Behind, the Hillcrest, Astoria and Blackstone face Olive Street.

The Belmont is leased to hotel chain operators Porter and Knapp in 1941, who sink scads of dough in her, reopening the pool, enlarging and refurbishing the roof garden, refurnishing and redecorating the rooms. But all that money couldn‘t stem the decline of the neighborhood.

Two codgers stroll Hill in the early 60s; they‘ll cadge together enough for a fifth and head to Pershing Square to argue Bay of Pigs for the afternoon. Then it‘s back to the Belmont for a nap.

A fire that would have felled a lesser building broke out November 3, 1967. The sixth-floor room of John Riles, 69, believed to have been smoking in bed, went up in flames, engulfing a good bit of that floor and part of the seventh, and all of the late John Riles.

A fire that would have felled a lesser building broke out November 3, 1967. The sixth-floor room of John Riles, 69, believed to have been smoking in bed, went up in flames, engulfing a good bit of that floor and part of the seventh, and all of the late John Riles.

What fire couldn‘t do to the Belmont, the CRA could; the summer of 1971 saw the Bunker Hill Redevelopment Project at the tail-end of its demolitions and the YWCA/Union League/Belmont, one of the last standing Stalwarts, tumbled under wreckers‘ hammers.

Find the big red awning–across from the MTA bus parked at the Third Street curb–jutting out from Angelus Plaza: that‘s 255 S. Hill, once the address that marked the western edge of the Belmont. As can be seen, near the site of the Belmont, there‘s a building of vaguely similar size and shape. Close, but as a gal from the YWCA might point out, no cigar.

Find the big red awning–across from the MTA bus parked at the Third Street curb–jutting out from Angelus Plaza: that‘s 255 S. Hill, once the address that marked the western edge of the Belmont. As can be seen, near the site of the Belmont, there‘s a building of vaguely similar size and shape. Close, but as a gal from the YWCA might point out, no cigar.

Photos from the USC Digital Archives, save for the “old codger” pic, William Reagh Collection, California History Section, California State Library; Belmont and lobby postcard, author; the image of the YWCA interior court borrowed from this page of A Visit to Old Los Angeles. As always, mad props to the Sanborn surveyors.

Hey kids! Grab your duffels and get on the bus. We‘re headed into the wilds of Exposition Park, to the Natural History Museum. No Timmy, and sorry Susie, no dinosaur bones or stuffed lions today; prepare to be shrunk like Bugaloos and fly! Fly over Bunker Hill! Bunker Hill–1940.

Hey kids! Grab your duffels and get on the bus. We‘re headed into the wilds of Exposition Park, to the Natural History Museum. No Timmy, and sorry Susie, no dinosaur bones or stuffed lions today; prepare to be shrunk like Bugaloos and fly! Fly over Bunker Hill! Bunker Hill–1940.

In that our post about the earth carvings (the Cuscans have nothing on us) at Second and Hill garnered some interest, I thought it worthwhile to detail salient features and goings-on sundry of other buildings on the block.

In that our post about the earth carvings (the Cuscans have nothing on us) at Second and Hill garnered some interest, I thought it worthwhile to detail salient features and goings-on sundry of other buildings on the block.

Not a lot of Postwar noirisme at the El Moro, if you‘re after that sort of thing. Mrs. Mollie Lahiff, 50, died of (what the papers termed) accidental asphyxiation after a gas heater used up all the oxygen in her tightly sealed room, February 26, 1953. Should you be so inclined, consider how drafty these places tend to be. Tightly sealed takes some doing. Just saying.

Not a lot of Postwar noirisme at the El Moro, if you‘re after that sort of thing. Mrs. Mollie Lahiff, 50, died of (what the papers termed) accidental asphyxiation after a gas heater used up all the oxygen in her tightly sealed room, February 26, 1953. Should you be so inclined, consider how drafty these places tend to be. Tightly sealed takes some doing. Just saying.

A favorite phrase of Edwardian Angeles is “sneak thief,” and Bunker Hill sneak thieves were forever securing some silver coinage here and a jeweled stick-pin there; on August 17, 1903, for example, during Mrs. H. Ware‘s temporary absence from 132, a sneak thief entered and stole $10 and a gold watch (a similar burglary occurred that same day, where at 104 S. Olive a room occupied by Mrs. Case was ransacked and liberated of $20).

A favorite phrase of Edwardian Angeles is “sneak thief,” and Bunker Hill sneak thieves were forever securing some silver coinage here and a jeweled stick-pin there; on August 17, 1903, for example, during Mrs. H. Ware‘s temporary absence from 132, a sneak thief entered and stole $10 and a gold watch (a similar burglary occurred that same day, where at 104 S. Olive a room occupied by Mrs. Case was ransacked and liberated of $20).

July 30, 1954. Jesus Chaffino is a 2 year-old with a talent for opening doors. Apparently his mother, Maria Avila, didn‘t tell her sister-in-law that when she left her place at 121 North Hope and dropped of the Jesus at 132 S. Olive. He was turned over to juvenile officers when he was found wandering near First and Olive at five a.m.

July 30, 1954. Jesus Chaffino is a 2 year-old with a talent for opening doors. Apparently his mother, Maria Avila, didn‘t tell her sister-in-law that when she left her place at 121 North Hope and dropped of the Jesus at 132 S. Olive. He was turned over to juvenile officers when he was found wandering near First and Olive at five a.m.

July 16, 1907. A burglar was detected working the window at Mrs. M. M. Clay‘s apartment house, 425, by her daughter, Clara Clay. She exclaimed under her breath to a Mr. Charles See, who kept the apartment above hers, “There‘s a man trying my window.”

July 16, 1907. A burglar was detected working the window at Mrs. M. M. Clay‘s apartment house, 425, by her daughter, Clara Clay. She exclaimed under her breath to a Mr. Charles See, who kept the apartment above hers, “There‘s a man trying my window.”