Bunker Hill of old is gone, never to be again. Until we concoct some Disneyesque Colonial Williamsburgian simulacrum, complete with sullen teenagers hired to pose as grimy grifters, we‘ll never be able to amble down Third toward Hill and catch Angels Flight up to battenboard and gingerbread. (Imagine, the collapse of the Vanderbilt will be repeated at two, four, and six! Visit the souvenir stand outside the Elmar! We gotta get Eco on board. Dang, too bad Baudrillard just died.)

Bunker Hill of old is gone, never to be again. Until we concoct some Disneyesque Colonial Williamsburgian simulacrum, complete with sullen teenagers hired to pose as grimy grifters, we‘ll never be able to amble down Third toward Hill and catch Angels Flight up to battenboard and gingerbread. (Imagine, the collapse of the Vanderbilt will be repeated at two, four, and six! Visit the souvenir stand outside the Elmar! We gotta get Eco on board. Dang, too bad Baudrillard just died.)

But the Hill did rise again, for one brief moment, when Robert “Chinatown” Towne said full speed ahead, we‘re building this thing. We‘ve got Ask the Dust to film. And with all that devalued Rand, what did they build down in a Capetown rugby field? A presumptuous pastiche. A goofy Golem. A dopey doppelgänger.

Bear in mind this post is less a criticism than an investigation, because it‘s not so much they got it wrong as they got it weird.

What is this Asking of Dust, you ask? Fine, a little background. It‘s the 1930s, and while the world was awash in novels of the mannered drawing-room variety, aspiring writer John Fante was banging out gritty realism, as best he could, considering that at every turn he‘d find the “mechanism of [his] new typewriter glutted with sand.” This is the titular dust, the tiny brown grains that‘d blow in from the Mojave, that‘d get in his hair and ears and find its way into the bedsheets of his little room at the Alta Loma, his Bunker Hill flop.

What is this Asking of Dust, you ask? Fine, a little background. It‘s the 1930s, and while the world was awash in novels of the mannered drawing-room variety, aspiring writer John Fante was banging out gritty realism, as best he could, considering that at every turn he‘d find the “mechanism of [his] new typewriter glutted with sand.” This is the titular dust, the tiny brown grains that‘d blow in from the Mojave, that‘d get in his hair and ears and find its way into the bedsheets of his little room at the Alta Loma, his Bunker Hill flop.

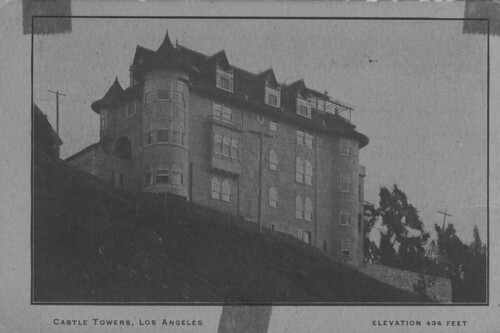

Ask the Dust is Bunker Hill. And AtD‘s protagonist Arturo Bandini is our displaced dago everyman, there at the Alta Loma, built on the hillside in reverse: he climbs out the window and scales the incline to the top of the Hill and walks “down Olive Street past a dirty yellow apartment house still wet like a blotter from last night‘s fog.” Via Fante/Bandini‘s description, the Hill takes on all necessary romance and despair:

I went up to my room, up the dusty stairs of Bunker Hill, past the soot-covered frame buildings along that dark street, sand and oil and grease choking the futile palm trees standing like dying prisoners, chained to a little plot of ground with black pavement hiding their feet. Dust and old buildings and old people sitting at windows, old people tottering out of doors, old people moving painfully along the dark street.

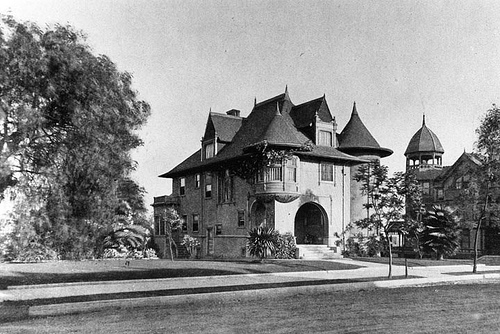

(In actuality, Fante wrote Ask the Dust in a [recently-demolished] pad on Berendo. But he had lived at the Alta Vista, seen here…

….and whose plot is now here:)

Anyway. Robert Towne reads the 1939-published Ask the Dust in 1971 while doing research for Chinatown. Towne decides then and there to make a picture out of the novel; it takes him a while to do so. Come 2006, voila, Ask the Dust.

I won‘t comment on the performances or the diegetic structure of this oft-maligned film. While the reviewers cobbled cranky critiques, none cast aspersions on this piece of celluloid for any abuse of architectural accuracy. I would, however, were I to have an appropriate forum to do so. This being barely it, we‘re off to the races.

Towne beat his brains out making this movie, befriending Fante, writing the script on spec (unheard of for a man of his stature), jumping through every archetypally ugly financing hoop and unearthing some undiscovered ones in the process. But yes, this labor of love paid off, because I was there opening day, ignoring the performances and diegetic structure to sit gape-mouthed at–what else? Bunker Hill. And sit in wonder and disbelief I did, mostly at the sheer strange world into which I‘d been injected: Bunker Hill was dementedly askew. Therefore I was dementedly askew. Well, Mr. D.A., I hear you say, if you‘re so All That, you try to make period picture.

I may only know the bare minimum about making period pictures, but at least it‘s something. Ten years ago, Richard and I–Kim‘s Richard, builder of this blog–were the art department for “indie” film Treasure Island. Treasure Island was shot on film and set in 1945–and who on earth has ever made a serious period feature with no budget? We built sets in a makeshift soundstage, shot at locations with cajoled props in a manner that would make Ed Wood blush, and shut down City streets (necessary when staging a riot). That‘s how you make a big, sprawling period picture (which went on to win the top honors at Sundance, the “Special Jury Prize for Distinctive Vision in Filmaking,” aka the coveted “What the Hell was That?! Award”) for less than the latte budget of Beverly Hills Chihuahua: make sure you have neither money nor expertise. But I‘m not here to impugn the excesses of studio excrescence. I‘m just pointing out that we did more with less. We were historically accurate. To an annoying degree.

I may only know the bare minimum about making period pictures, but at least it‘s something. Ten years ago, Richard and I–Kim‘s Richard, builder of this blog–were the art department for “indie” film Treasure Island. Treasure Island was shot on film and set in 1945–and who on earth has ever made a serious period feature with no budget? We built sets in a makeshift soundstage, shot at locations with cajoled props in a manner that would make Ed Wood blush, and shut down City streets (necessary when staging a riot). That‘s how you make a big, sprawling period picture (which went on to win the top honors at Sundance, the “Special Jury Prize for Distinctive Vision in Filmaking,” aka the coveted “What the Hell was That?! Award”) for less than the latte budget of Beverly Hills Chihuahua: make sure you have neither money nor expertise. But I‘m not here to impugn the excesses of studio excrescence. I‘m just pointing out that we did more with less. We were historically accurate. To an annoying degree.

Ask the Dust, less so. Oh, it looks great, but it‘s Bunker Hill Bizarro. Batman once pointed out to the Mystery gang that the Joker did first-rate counterfeiting, save for one thing: President Lincoln never wore a turtleneck sweater. Suffice it to say, Bunker Hill‘s neck will never get cold.

Consider. Towne was in development on this project for thirty years. During that time he could have learned the difference between the Second and Third Street tunnels. Or spent an hour finding someone who did. Look, no-one is here to talk smack about Ask the Dust Production Designer Dennis Gassner. Many have gone into production design to be Dennis Gassner. And the production looks terrific–but there are those among us will forever be at a loss to understand what the hell it was that Towne/Gassner & his team/whoever‘s responsible was doing.

Ask the Dust–it‘s not that it‘s full of rampant anachronism (if The Sting is set in the 30s, why are they listening to 1890s Scott Joplin, and have 1970s hair?), nor does it feel just altogether wrong & parachronistic (Ha! Ha! Harlem Nights!)–no, it‘s anatopistic, which is a ten-dollar word meaning strange as all get out. Instead of mere chronological anomaly, we have full-bore objet-out-of-place, for example, a tunnel that‘s moved over. (I‘m just talking about the giant corporeal set they built. The actual CGI they dropped on top of it is a monument to chronological anomaly. We‘ll get to that.)

Let‘s talk tunnels. The designers read the script, and it says Angels Flight, Third Street. Ok. Art Department gets to work. Now then:

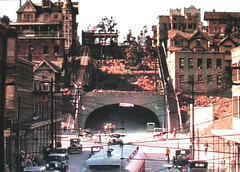

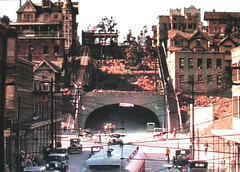

This is the Third Street tunnel:

This is the Second Street tunnel:

This is what they elected to build:

Hence:

Got it? It‘s the Second Street tunnel with Angels Flight next to it. And other Third Street whatnot atop. Some of it, anyhow.

This is no mere clickety-clack of computer, or making of matte painting (do people still do those?), this was built:

1924 looked just like 2004…

Yes, I find this peternaturally exciting, but then, I need to get out more. In any event:

Let’s again turn our attention to AtD‘s world of Third and Hill, 1933.

Here then is your standard pre-June 1908 Crocker Mansion shot. There‘s the Crock, the observation tower, no Elks gate of course. Down from the Crocker there‘s the Nelson House and the Ferguson house. On the east side of the street, in descending order, the Hillcrest, the Sunshine Apartments, the McCoy House, and the St. Helena Sanitarium.

What I find really intriguing in Ask the Dust‘s interpretation is the inclusion of the six-bay arched entry to Angels Flight, up top on Olive Street (you can see four of the open bays because the two on the left were closed in for the ticket booth). This pavilion would naturally butt up against the Hillcrest, but because the tunnel below is now so wide, there exists this odd empty area. The six-bay pavilion up top also thrusts us into an all the more peculiar place within the time-space continuum; it only existed between 1910 and 1914. While the Crocker Mansion existed before 1908. And the here-absent Observation Tower was not removed until 1938, five years after the Ask the Dust shot was “taken.”

What I find really intriguing in Ask the Dust‘s interpretation is the inclusion of the six-bay arched entry to Angels Flight, up top on Olive Street (you can see four of the open bays because the two on the left were closed in for the ticket booth). This pavilion would naturally butt up against the Hillcrest, but because the tunnel below is now so wide, there exists this odd empty area. The six-bay pavilion up top also thrusts us into an all the more peculiar place within the time-space continuum; it only existed between 1910 and 1914. While the Crocker Mansion existed before 1908. And the here-absent Observation Tower was not removed until 1938, five years after the Ask the Dust shot was “taken.”

So why use the Second Street tunnel and not the Third? I have a possible explanation for this. Here is a passage from the book:

I took the steps down Angel‘s Flight to Hill Street: a hundred and forty steps, with tight fists, frightened of no man, but scared of the Third Street Tunnel, scared to walk through it–claustrophobia.

So there you have it. They couldn‘t build the Third Street tunnel because Bandini‘s character was scared of”¦so they built the”¦OK, so there was a time when everyone was coked out of their skulls and something like that could have occured. But nowadays there‘s oversight, and bottom lines, and so on. Right?

But go back to the Ask the Dust image. The (pre-1933) Ferguson home down on the street by Angels Flight is sort of correct, though its gable faced at an angle to the street. And where is the entry arch to Angels Flight, pre-1910 or post? The buildings on the other side of the street are entirely fanciful”¦vaguely correct in their massing, but that‘s about it. The Hillcrest never had bay windows. The McCoy house wasn‘t double gabled–and the Sunshine Apts are gone, presumably so that the Sanitarium could be shoved up the hill.

In theory Gassner made a conscious aesthetic decision to go with the Crocker because it played better visually. Or there was an unpaid intern who saw a stack of postcards and slapped this together.

(Someone apparently saw an image of the Bath Block, once on the SW corner of Fifth and Hill.)

It doesn‘t seem to bother Bandini much that he lives in a counterfactual alternate time universe. (Also, the Confederacy won, and because of that we have gills. Perhaps, rather than being doomed to an episode of Sliders, Bandini‘s existence in this new world of speculative fiction where the Crocker survives is more akin to Delenda Est, and isn‘t, therefore, you know, that bad?)

What‘s also interesting is that Bandini doesn‘t actually live on Bunker Hill. The Alta Loma slopes down to Hill Street, in the middle of the 300 block–to the right of the St. Paul neon.

What‘s also interesting is that Bandini doesn‘t actually live on Bunker Hill. The Alta Loma slopes down to Hill Street, in the middle of the 300 block–to the right of the St. Paul neon.

Back in the day, in the 300 block, that St. Paul Hotel was the site of the Western Mutual Life Bldng, the Alta Loma where the Hotel Columbia stood.

A shot from the Graf:

The entrance to the tunnel is on the right; the Alta Loma, bottom center.

Let us note too that while they built this:

It gets barely a nod in the film. (Probably because while they constructed a working PE Red Car that got lots of camera time, there were no Olivet or Sinai.) Nevertheless, it‘s all the more effective when we‘re not hit over the head with the thing.

I don‘t even want to discuss the unexplainable “flying in” opening credits–which, of course, is exactly what I‘m going to do. So we‘re flying in, and Bunker Hill has all of, oh, nine structures, and Bandini‘s Alta Loma on Third is one of them, which we recognize as 512 West Second Street, once just above the Second Street tunnel:

I could go on and on (haven‘t even deconstructed Third Street) but think I‘ve made my point: weird, and enjoyably so. It‘s not that the sets were treif out of lack of effort. They had the opportunity to rebuild Bunker Hill from the Ground Up, something never attempted before and will likely never happen again (until I‘m given thirty-six acres and a drunken bank president), and I commend them for doing most impressive work:

(The first rule of any period LA picture: when in doubt, stick City Hall in there.)

Yes, impressive, impressive work. Now consider, if all had been perfect, what would I have had to write about?

I should point out as well that the costuming was first-rate (Albert Wolsky won the Oscar for Bugsy).

Bet when you got up this morning you weren‘t wondering whether you‘d see Arturo Bandini with his Discman today.

For more on Fante and Bunker Hill, ask a teacher or librarian. Or better yet, get on the bus.

Speaking of CGI, what’s next on deck? Again starring our City Hall, CGI removing modernity like debridement.

Yes, Changeling. Which yeah, I‘ll see in the theater, but won‘t be as good as Choke, because it‘s about a woman yelling “Give me back my son!” and also because they shot it in San Bernardino and San Dimas.

I get so tired of hearing about you can‘t shoot old LA because there‘s no old LA left in which to shoot (yes, I know they‘re not actually just sloppy and lazy; it‘s just a disingenuous way to get around verbalizing that it‘s cheaper to shoot in fill-in-the-blank). But give me a camera and some crazy people and twelve dollars I‘ll make you the best damn Bunker Hill movie yet.

2nd St. tunnel 1923, TICOR/Pierce Collection, University of Southern California; Alta Vista, Bath Block, 215 W 2nd, 2nd St tunnel 1960, Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library; I especially want to thank Jon, Lead Fabricator for AtD‘s Art Department and his collection of images without which this post wouldn’t have been nearly as complete; Bandini and his Discman, and the Third and Hill mock up, come from here; the shot of the set from above is from here; super special thanks to the good people at Viacom/Paramount Motion Picture Group for not sending their thugs and/or lawyers after me, because they are I‘m sure very nice people. Oh, I also stole screen grabs from that GE/Vivendi "Changeling" thingy. I am so headed for an earthen dam.

Bunker Hill of old is gone, never to be again. Until we concoct some Disneyesque Colonial Williamsburgian simulacrum, complete with sullen teenagers hired to pose as grimy grifters, we‘ll never be able to amble down Third toward Hill and catch Angels Flight up to battenboard and gingerbread. (Imagine, the collapse of the Vanderbilt will be repeated at two, four, and six! Visit the souvenir stand outside the Elmar! We gotta get Eco on board. Dang, too bad Baudrillard just died.)

Bunker Hill of old is gone, never to be again. Until we concoct some Disneyesque Colonial Williamsburgian simulacrum, complete with sullen teenagers hired to pose as grimy grifters, we‘ll never be able to amble down Third toward Hill and catch Angels Flight up to battenboard and gingerbread. (Imagine, the collapse of the Vanderbilt will be repeated at two, four, and six! Visit the souvenir stand outside the Elmar! We gotta get Eco on board. Dang, too bad Baudrillard just died.) What is this Asking of Dust, you ask? Fine, a little background. It‘s the 1930s, and while the world was awash in novels of the mannered drawing-room variety, aspiring writer John Fante was banging out gritty realism, as best he could, considering that at every turn he‘d find the “mechanism of [his] new typewriter glutted with sand.” This is the titular dust, the tiny brown grains that‘d blow in from the Mojave, that‘d get in his hair and ears and find its way into the bedsheets of his little room at the Alta Loma, his Bunker Hill flop.

What is this Asking of Dust, you ask? Fine, a little background. It‘s the 1930s, and while the world was awash in novels of the mannered drawing-room variety, aspiring writer John Fante was banging out gritty realism, as best he could, considering that at every turn he‘d find the “mechanism of [his] new typewriter glutted with sand.” This is the titular dust, the tiny brown grains that‘d blow in from the Mojave, that‘d get in his hair and ears and find its way into the bedsheets of his little room at the Alta Loma, his Bunker Hill flop.

I may only know the bare minimum about making period pictures, but at least it‘s something. Ten years ago, Richard and I–Kim‘s Richard, builder of this blog–were the art department for “indie” film

I may only know the bare minimum about making period pictures, but at least it‘s something. Ten years ago, Richard and I–Kim‘s Richard, builder of this blog–were the art department for “indie” film

What I find really intriguing in Ask the Dust‘s interpretation is the inclusion of the six-bay arched entry to Angels Flight, up top on Olive Street (you can see four of the open bays because the two on the left were closed in for the ticket booth). This pavilion would naturally butt up against the Hillcrest, but because the tunnel below is now so wide, there exists this odd empty area. The six-bay pavilion up top also thrusts us into an all the more peculiar place within the time-space continuum; it only existed between 1910 and 1914. While the Crocker Mansion existed before 1908. And the here-absent Observation Tower was not removed until 1938, five years after the Ask the Dust shot was “taken.”

What I find really intriguing in Ask the Dust‘s interpretation is the inclusion of the six-bay arched entry to Angels Flight, up top on Olive Street (you can see four of the open bays because the two on the left were closed in for the ticket booth). This pavilion would naturally butt up against the Hillcrest, but because the tunnel below is now so wide, there exists this odd empty area. The six-bay pavilion up top also thrusts us into an all the more peculiar place within the time-space continuum; it only existed between 1910 and 1914. While the Crocker Mansion existed before 1908. And the here-absent Observation Tower was not removed until 1938, five years after the Ask the Dust shot was “taken.”

What‘s also interesting is that Bandini doesn‘t actually live on Bunker Hill. The Alta Loma slopes down to Hill Street, in the middle of the 300 block–to the right of the St. Paul neon.

What‘s also interesting is that Bandini doesn‘t actually live on Bunker Hill. The Alta Loma slopes down to Hill Street, in the middle of the 300 block–to the right of the St. Paul neon.

When the residents of Bunker Hill discovered that the Alameda Street crib district prostitutes were living in their neighborhood, they drafted polite letters to the City Council and the Police Commission complaining about it.

When the residents of Bunker Hill discovered that the Alameda Street crib district prostitutes were living in their neighborhood, they drafted polite letters to the City Council and the Police Commission complaining about it. Based out of Denver, leaders of the Burning Bush flock came to Los Angeles in the spring of 1904, and wasted no time in luring converts. In addition to their base of operations near Angel’s Flight at 315 Olive Street, they also established a revival tent at the corner of Spring and Seventh. At meetings, their followers would regularly shout, leap up and down, speak in tongues, and fall into semi-catatonic states for hours at a time. So enthusiastic were their cries that neighbors claimed they drowned out the sound of the streetcar as it rattled up the hill.

Based out of Denver, leaders of the Burning Bush flock came to Los Angeles in the spring of 1904, and wasted no time in luring converts. In addition to their base of operations near Angel’s Flight at 315 Olive Street, they also established a revival tent at the corner of Spring and Seventh. At meetings, their followers would regularly shout, leap up and down, speak in tongues, and fall into semi-catatonic states for hours at a time. So enthusiastic were their cries that neighbors claimed they drowned out the sound of the streetcar as it rattled up the hill. Despite the leaping, members of the Burning Bush were not to be confused with the Holy Jumpers, another evangelical sect that had come to Los Angeles around the same time. Though they operated on a similar set of beliefs, the Burning Bush was generally considered to be less objectionable than the Holy Jumpers because they were not quite so loud. Additionally, while the Burning Bush had culled its leaders from respectable cities like Denver and Boston, the Holy Jumpers were from Alabama (gasp).

Despite the leaping, members of the Burning Bush were not to be confused with the Holy Jumpers, another evangelical sect that had come to Los Angeles around the same time. Though they operated on a similar set of beliefs, the Burning Bush was generally considered to be less objectionable than the Holy Jumpers because they were not quite so loud. Additionally, while the Burning Bush had culled its leaders from respectable cities like Denver and Boston, the Holy Jumpers were from Alabama (gasp).

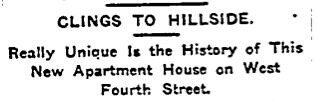

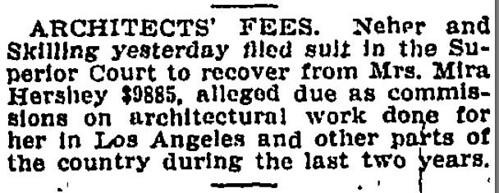

One cannot help but be enamored of the Nugent. Maybe it‘s the big spooky tower. Maybe it‘s the Nugent‘s corner site at Third Street and Grand Avenue…3rd & Grand just purrs off the tongue, which only seems to further imbue that location with the status as Ground Zero, Bunker Hill.

One cannot help but be enamored of the Nugent. Maybe it‘s the big spooky tower. Maybe it‘s the Nugent‘s corner site at Third Street and Grand Avenue…3rd & Grand just purrs off the tongue, which only seems to further imbue that location with the status as Ground Zero, Bunker Hill.  The Nugent‘s most notable resident was a Southern Pacific brakeman by the name of Walter J. Dean. It was March 10, 1935, and Dean was busy plying his honest trade out in Pomona at a railroad right of way while a train crew was switching freight cars in the local yards. Then some woman, as high and as mighty as they come, decided to drive her automobile across said railroad right of way; this enraged Dean, who pitched his lantern through her car windshield. Unfortunately the woman was Mrs. Lois Browning, wife of Desk Sergeant Browning of the local police force, which might give some insight into her high-and-mightiness.

The Nugent‘s most notable resident was a Southern Pacific brakeman by the name of Walter J. Dean. It was March 10, 1935, and Dean was busy plying his honest trade out in Pomona at a railroad right of way while a train crew was switching freight cars in the local yards. Then some woman, as high and as mighty as they come, decided to drive her automobile across said railroad right of way; this enraged Dean, who pitched his lantern through her car windshield. Unfortunately the woman was Mrs. Lois Browning, wife of Desk Sergeant Browning of the local police force, which might give some insight into her high-and-mightiness.

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

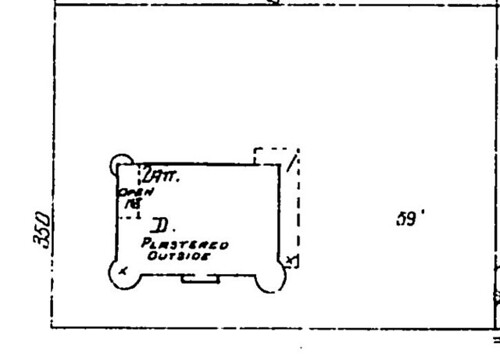

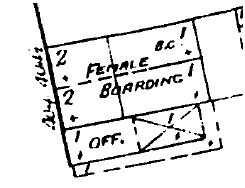

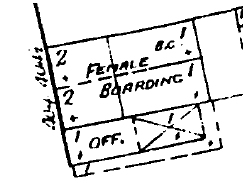

However, the most notorious eyesores were the single-story, ramshackle cribs on Alameda, long rows of narrow rooms that prostitutes could rent by the night, at exorbitant rates, designated here on the Sanborn maps as "female boarding." The Alameda cribs were visible from the nearby Southern Pacific line, and rail passengers on their way to Los Angeles would gawk out the windows at prostitutes soliciting business from the sidewalks.

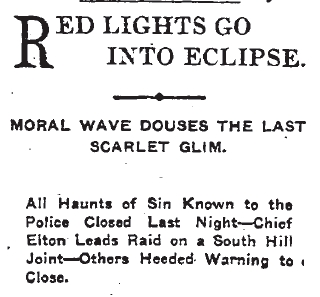

However, the most notorious eyesores were the single-story, ramshackle cribs on Alameda, long rows of narrow rooms that prostitutes could rent by the night, at exorbitant rates, designated here on the Sanborn maps as "female boarding." The Alameda cribs were visible from the nearby Southern Pacific line, and rail passengers on their way to Los Angeles would gawk out the windows at prostitutes soliciting business from the sidewalks. On March 31, 1904, police raided an establishment at 355 South Hill Street, operated by Ethel Wood. She was arrested along with three women, Mabel Stone, Dolly Long, and Hattie Jones. The four appeared in court the next day, all wearing long black veils to frustrate the looky-loos.

On March 31, 1904, police raided an establishment at 355 South Hill Street, operated by Ethel Wood. She was arrested along with three women, Mabel Stone, Dolly Long, and Hattie Jones. The four appeared in court the next day, all wearing long black veils to frustrate the looky-loos.