In the first installment of our series on George Mann’s newly-discovered vintage Los Angeles restaurant photos, we introduced you to Mann’s custom 3-D photo viewer, which provided free entertainment to patrons as they waited to be seated in numerous L.A. restaurants, and to images of the Malibu restaurants that were displayed inside the viewers. In the second entry in the series, we toured the Bixby Knolls neighborhood of Long Beach, home of some gorgeous, long-demolished restaurants–and a surprising survivor.

Today, our travels with George take us along that famously upscale diner’s boulevard, La Cienega–known for more than half a century as Restaurant Row. While its luster is today rather dimmed, in the mid-1950s the establishments along La Cienega were the city’s most beautiful, and their kitchens turned out meals which, if not innovative, were certainly expensive and unabashedly Continental. In the absence of a dedicated foodie culture, Restaurant Row was where one went to eat high on the proverbial hog.

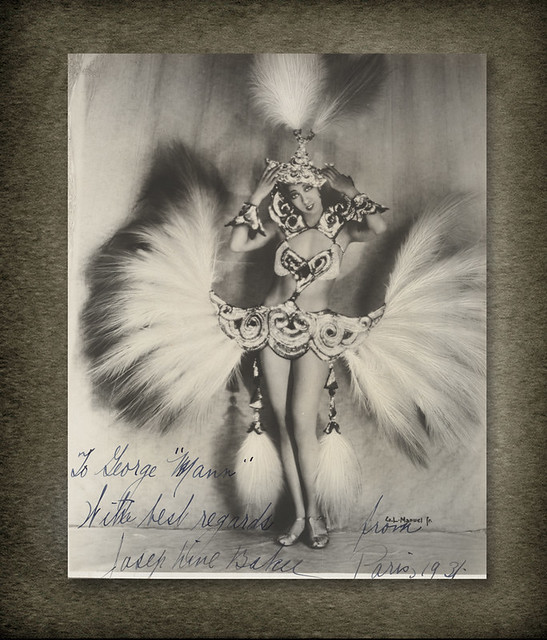

photo: George Mann

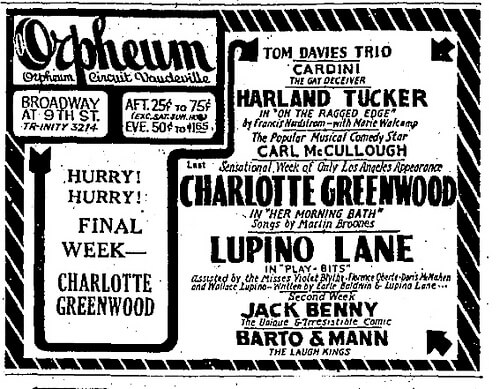

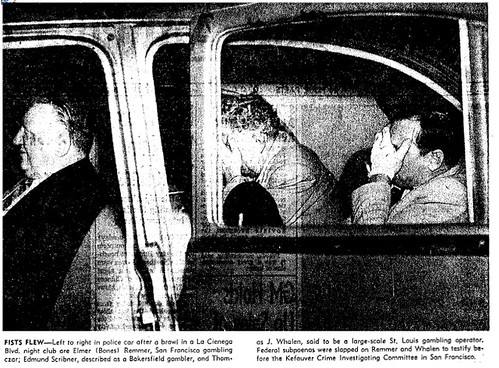

We begin a few blocks south of Santa Monica, where George recorded the fact that the Walter Gross Trio are appearing nightly at the Encore cocktail lounge and supper club. At first we wondered if the photo might have been taken in March 1953, when press clips show the band had an Encore booking.

photo: George Mann (detail)

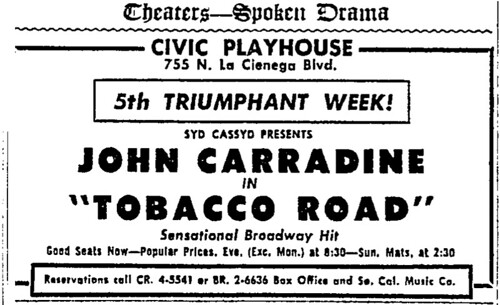

But the poster on the phone pole, advertising John Carradine’s turn as Jeeter Lester in Tobacco Road at the Civic Playhouse dates the shot to early 1954, suggesting that the Encore’s clientele dug Walter Gross’ Trio quite a lot.

Pianist Gross is best known for his composition “Tenderly.” We’re partial to Nat Cole’s interpretation.

In 1946, the building at 806 N. La Cienega was home to Billy Gordon Originals, a custom fashion emporium, and by the late 1970s, it was the Jeffrey Horvitz art gallery. In years between, it was the Encore, a joint that was something of a magnet for trouble.

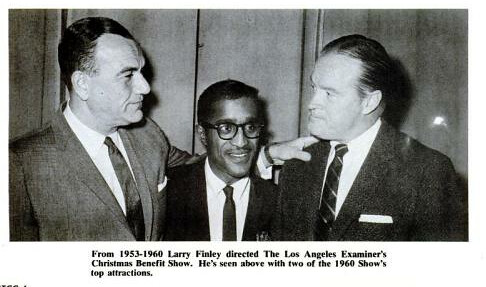

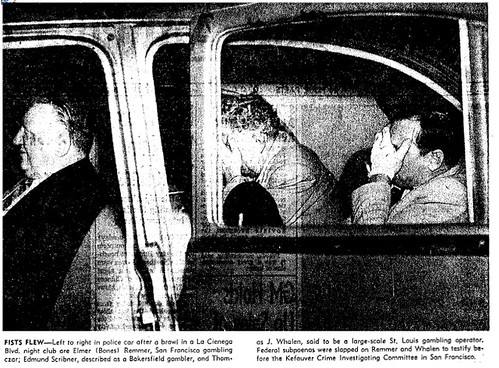

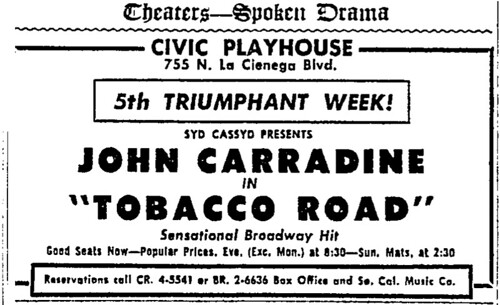

Left to Right: Remmer, Scribner, Whalen. Photo: L.A. Times

In December 1950, local cops swept up a rat king of drunken gamblers after an early morning brawl inside the Encore, resulting in the feds calling a pair of long-sought men to appear before the Kefauver Senate Crime Investigating Committee. Invited to Washington were Elmer “Bones” Remmer (San Francisco) and Thomas J. Whalen (East Saint Louis). With them in the Encore, and booked on charges of intoxication were Edmund M. Scribner (Bakersfield tavern keeper) and redheaded Miss Vici Raaf, actress.

Photo: L.A. Times

Whalen was also charged with robbery and carrying a concealed weapon after a search turned up a .25-caliber automatic hidden in the padding of his car, and $4600 cash. The cops arrested the quartet after Andy McIntyre, proprietor, called for help with some brawling football fans. Whalen was passed out on the floor when deputy sheriffs and Highway Patrolmen arrived, Miss Raaf, Whalen’s housemate above the Sunset Strip, bending over him.

Remmer, who Miss Raaf identified as the operator of the Cal-Neva Lodge — which he was supposed to have sold under duress in 1948 — cursed at and threatened officers and reporters. Sheriffs interrogated the men about the recent Samuel Rummel gang slaying in Laurel Canyon, and told them all to stay out of Los Angeles.

In May 1961, piano man Bobby Troup (aka Mr. Julie London), the regular headliner, was jumped in the parking lot, and punched so hard he lost three teeth. His assailant, coffee salesman Stan Massey, 35, was apparently incensed because the performer spoke with a woman in Massey’s party. Gary Shugart, parking lot attendant, said Massey called Troup out of his car, then started swinging while the other man was off guard. Massey countered that Troup pushed him first, and that he thought the clock (?!) in Troup’s hand could be used as a weapon. Massey was convicted of assault and fined $140. Troup sought $68,305 in civil damages, but if he prevailed, that didn’t make the papers. Troup played a mean “Tenderly,” too.

December 30, 1964 was a Wednesday night. Quiet. George E. Davidson, 50-year-old west side accountant, met his draftsman friend Jose G. Beltran, 29, at the Encore. A shoving match ensued over who was going to pay the bill, Davidson fell, struck his head, and died a few days later. Beltran was picked up at home in Monrovia and charged with murder, after which the sad story vanishes from the press.

But it wasn’t all fisticuffs. If you swung by the place on September 19, 1961, a dinner meeting of the Los Angeles Junior Advertising Club would include discussion on the theme “Entertainment in Advertising,” and far as we know, not one junior exec was left bloody.

Before we leave the Encore, please note that a couple doors north is another handsome neon sign in the exact same shades of green and yellow, advertising Talk o’ the Town Coiffeur. We suspect that George Mann, who loved stylish signage, snapped the Encore in the manner he did to include both signs in his composition.

photo: George Mann (detail)

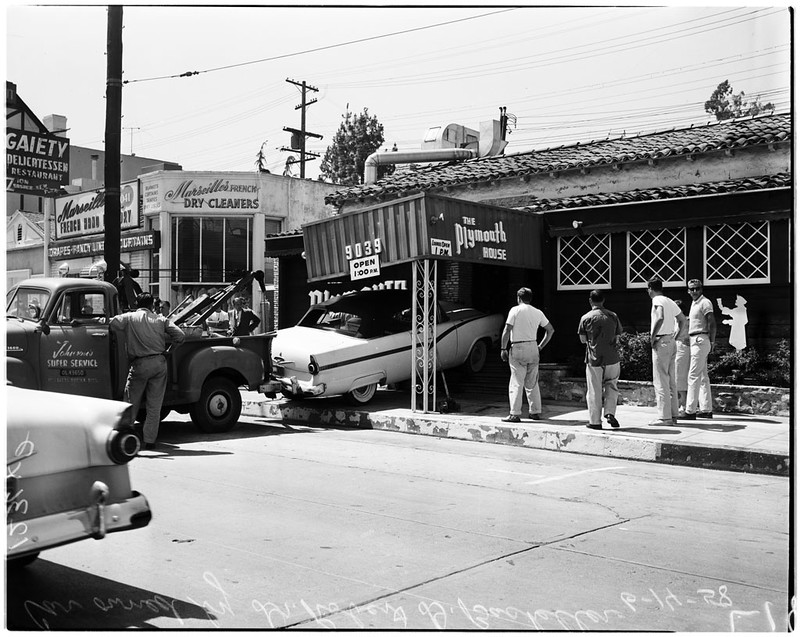

Down the road at Melrose we find The Bantam Cock, which was the second Restaurant Row establishment of Shelton “Mac” McHenry, whose influential Tail o’ the Cock we’ll discuss at length when we near Wilshire Boulevard.

photo: George Mann

After the Bantam Cock opened in 1948, manager Jack Buchtel was sent off to Paris to study at the Cordon Bleu and gather recipes for the Bantam’s weekly special menu. The Bantam Cock was also among the first west coast restaurants to feature California wines alongside mid-range French imports.

You can’t have a prominent restaurant on the Row without making it into the crime beat, but it seems nothing too grim ever happened chez BC. There was that Sunday night after closing time in July 1952 when Buchtel was forced to open the safe for a pair of olive-skinned, gun-toting robbers, who got away with $3500–a pretty normal occurrence in this neighborhood in the gangster era.

Then in April 1954, actor Jack Webb, already famous as his Dragnet alter-ego, Sgt. Joe Friday, was enjoying a birthday dinner with the Dick Breens, when he was called to the phone. On the line, his frantic housekeeper Bertha Crigler, terrified that a prowler was pounding on the door screaming to be let into Webb’s home at 9102 Hazen Drive. “Come home, Mr. Webb!”

Dorothy McGuire with housekeeper-to-the-stars Bertha Crigler, 1941

When Webb arrived, he found John Trindle Camplin, 49, explaining to police that he’d been watching the Bobo Olson-Kid Gavilan fight at a party in the neighborhood, had a few drinks, then started arguing with his wife and went out to get some air. He was walking aimlessly and angrily when he spied Webb’s house and decided he’d bust his way in and use the phone. Camplin was booked on a drunkenness charge, and we imagine suffered a mental jolt when he spied Sgt. Joe Friday getting the lowdown on his case. (As for the fight, world Middleweight champ Bobo Olson kept his title in a decision after 15 brutal rounds.)

Stylistically, the Bantam Cock was notable for a mid-50s Mondrian-inspired remodel by architects John Rex and Douglas Honnold and a signature brass rooster sculpture by Diamond Chair designer Harry Bertoia. Gebhard and Winter liked it enough to cite the place in an early edition of their L.A. architecture guide.

In 1966, the Wednesday lunch special included a fashion show, with models strolling between the tables. Despite such appealing amenities, the restaurant closed in 1975.

photo: George Mann

Next on our circuit is Bruce Wong’s Ming Room, a classic piece of sign-heavy mid-century commercial architecture, photographed by George Mann in 1954.

One night in late 1952, Earl Wilson reported that Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio were canoodling over a bowl of something crispy when a guy a few tables over became hypnotized by Marilyn’s beauty, and sighed “Gee, isn’t she pretty?” His wife splashed hot soup in his face and ran off to the ladies room. The goof repeated his comment on her return and got a teapot smashed over his head. And Marilyn was still pretty.

For six months in 1965, the restaurant was Ron Waller’s Pro Room, a football-themed nightclub, which everyone involved had cause to regret.

While the Ming Room is long gone, it could almost be a twin of Club Tee Gee, which thrives along Glendale Boulevard in Atwater Village.

photo: George Mann

Sarnez was a dinner and dance spot, with your hosts Harry Ringland and Lew Sailee. That partially obstructed neon sign reads “A Fine Name In Food.”

In 1955, Danny Kaye was dropping by to dig jazzbo Red Nichols and his Five Pennies, whose life story Kaye was bringing to the screen. But by the mid-1950s, mentions in the society pages tapered off, and soon Sarnez was gone.

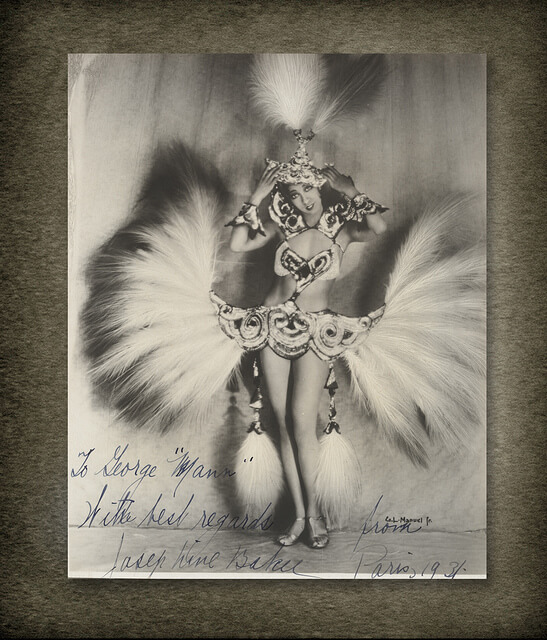

George Mann was on the same late Vaudeville bill with Red Nichols in Dallas in 1937, and shot a pair of handsome portraits.

Photo: George Mann

Photo: George Mann

Next door was Richlor’s, opened in 1941 and famed for its planked

hamburger steaks, billed as “a veritable symphony of flavor on an oak

plank!” (Believe it or not, gourmet burgers are not a 21st century innovation.)

photo: George Mann (detail)

Image: LAPL menu collection

Also on the menu were an umami-rich house salad of anchovies, bleu cheese and hardboiled egg, a selection of cold seafood salads (June Lockhart was a fan), sourdough toast topped with Lawry’s garlic spread (recipe furnished on request), French fried onions, fresh pies, hot coffee and unusually good mashed potatoes–a side dish the Richlor’s folk took so seriously, they assigned one chef to do nothing but see to those spuds, then festoon them around each burger on its wooden serving plank.

In 1960, Richlor’s released a startling, perhaps apocryphal statistic: since opening their seafood bar in 1942, more than 21 million shrimp had been served.

It’s said that Richlor’s was the favorite west coast haunt of J. Edgar Hoover, and we must admit, few things sound more appetizing than a planked burger and a chance to rub elbows in the gents with Washington’s toughest customer. (He was also partial to peach ice cream from the Farmer’s Market.)

As it happens, George Mann photographed the FBI’s main main twice, though not, to our grave disappointment, in the men’s room at Richlor’s. Below, on stage during a cameo appearance in Hellzapoppin, the enduring Broadway comedy in which George was featured with his dancing partner Dewey Barto…

Photo: George Mann

Photo: George Mann

…and above, in the audience yucking it up with longtime companion Clyde Tolson.

Image: LAPL menu collection

In case the Lawry’s garlic spread didn’t tip you off, Richlor’s was an offshoot of that legendary Restaurant Row establishment, it’s name a portmanteau of owner Lawrence Frank’s childrens’ names: Richard + Lorraine. In 1961, the Wayne McAllister-designed building was remodeled by decorator Robert Hanley as Lawry’s Mediterrania (home of the musical wine cart), and was later Ed Debevic’s, a retro diner. By that time, Richlor’s namesake Richard Lawrence was quite a macher along the boulevard.

photo: George Mann

Lawry’s itself isn’t far. The original restaurant opened in 1938, one of the first upscale eateries along what would become restaurant row. We see it here in its second incarnation, in the Wayne McAllister-designed monochromatic slab style, a building as simple and brown as the bill of fare within.

A partnership between Lawrence Frank and his brother-in-law Walter Van de Kamp, its wheeled carts have long dished out prime rib dinners and uncounted gallons of horseradish sauce to grads, grandmas and all between. And it’s remarkable as the only La Cienega restaurant photographed by George Mann to have survived into the 21st century.

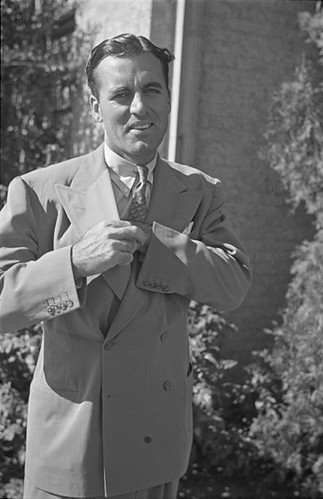

photo: George Mann

In July 1939, Shelton “Mac” McHenry’s 50-seat Tail O’ the Cock opened across the way, expanding and gaining a British makeover after the war. In 1959, restaurant critic Cordell Hicks noted “lots of businessmen–lots of men, period–go here. Substantial food.” A second branch opened on Ventura Boulevard near Coldwater in 1948.

Mac and wife Bernice were popular hosts, always ready to advise on European travel or throw a wingding for a football game, and their restaurants thrummed with live music and the comfortable rattling of ice for many decades. So welcoming did customers find the Tail O’ the Cock that some got their mail sent there.

Mac McHenry started out on the nascent Restaurant Row as assistant manager at the Somerset House, a private club for film and society folk opened in 1936 (Bing Crosby, Norma Talmadge and Carole Lombard were members). He was put into the position by someone who had a financial interest in the Somerset and wanted a man on the inside. Mac fell in love with the restaurant business, found a backer, and with John Hadley opened Tail O’ the Cock–the fourth restaurant on La Cienega after Lawry’s, Somerset House and Murphy’s.

Fun fact #1: When time came to put in a wine cellar, the tar that gives La Cienega its name proved too gooey, so a climate controlled attic was built instead.

In 1958, McHenry reminisced to Gene Sherman of the L.A. Times, “We wanted a warm decor and decided on the English tavern motif, now known as early La Cienega. We decided to employ Negro waiters because they have such an innate graciousness and eagerness to serve. We’ve been copied a lot there, too. When we opened, you could buy a lot on La Cienega for $2500 and today property is selling for $1500 a front foot. Why, I had to pay $167,000 for a parking lot across from the Bantam Cock, which is our smaller, more continental restaurant up the street. Today there are some 36 restaurants on the row and I’d guess the total investment in them runs close to $20,000,000. We figure 15,000 people a night dine along the row, with the average check maybe $7 or $8 a person.” (For comparison, rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the Wilshire district was about $100 in 1958.)

Fun fact #2: Legend has it that the Margarita cocktail was invented by Tail o’ the Cock head bartender Johnny Durlesser, and named after a customer called Margaret. This could even be true.

When Bernice McHenry died of cancer in 1983, the solicitous Mac asked the newspapers not to print her age. The McHenrys had already sold the restaurant to an investment group, but Mac stayed on, paying a high rent for the privilege of finishing out his career as a host. Lingering illness–a broken hip and a stroke– compelled Mac to shut the original Tail o’ the Cock on February 28, 1985; key staff were transferred to the Ventura Boulevard branch. The plan was to tear down the La Cienega building and replace it with a high rise Holiday Inn, but the project festered.

In 1986, Mac retired, and with little notice shuttered the valley restaurant, issuing a statement that he wanted this property to be redeveloped as a high end, Beverly Hills-style shopping center, and not left sitting empty as had been the case on La Cienega. But developer Herbert W. Piken’s ambitious plans for the site went unrealized as furious neighbors protested, and employees of many decades were cast to the winds, an ignominious end to a long tradition of service.

Mac McHenry died in July 1987. He was 77, and left no survivors save the Tail o’ the Pup hot dog stand (not a blood relative).

photo: George Mann

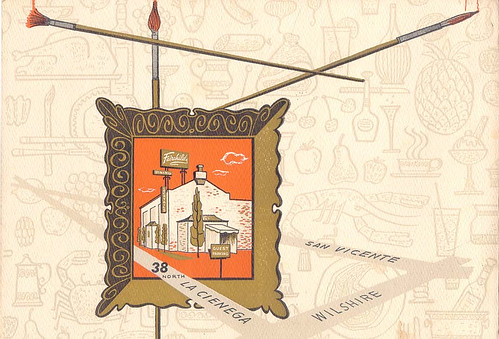

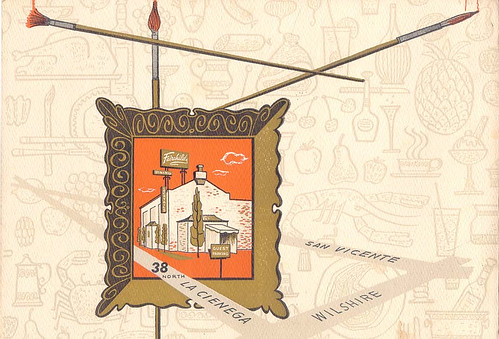

Our final stop on George Mann’s tour of grand eateries past is Fairchild’s, and while the photo is one of the least exciting in the series, researching it has taken us down some very dark and unexpected paths, revealing an incredible and rather horrifying story that will forever change the way we think about Restaurant Row. Consider yourself warned.

LA Public Library menu collection

Behind this modest Hollywood Regency exterior was Peter Fairchild’s pretentious domain, a restaurant that boasted a separate parking attendant to handle Rolls Royces and other high end vehicles, and an air-conditioned kennel with individual dog houses where kept women could park their poodles during multi-martini meals.

LA Public Library menu collection

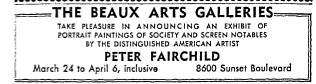

Fairchild, also known as a painter of celebrity portraits — Ava Gardner, Judy Garland, Joan Blondell, Lana Turner, Mickey Rooney, Gloria Vanderbilt and President Eisenhower were among his subjects — was backed by Wilshire Oil heiress Bessie Machris and her daughter Katherine in the establishment of his namesake restaurant and corporation, Restaurant Row Inc.

A 1961 review called this newest iteration of Fairchild’s (the restaurant was first opened in Spring 1953 in the old Cherio Room space) “frankly elegant” with red-coated waiters serving up tossed salads, snails and caviar amidst gilded banquettes. The specialty of the house was Langoustines Commanders, with other popular dishes including Coq au Vin and a trio of tenderloins (beef, veal and pork). For dessert, naturellement, cherries jubilee, chocolate mousse or a selection from the pastry tray.

In summer 1963, the Culinary Workers Union took advantage of a downturn in business to string a picket line in front of Fairchild’s. Staff abandoned ship, and the house musicians refused to cross the line. Fairchild brought in scabs to serve patrons, and made some noise about knocking down the restaurant to build an eight-story highrise with a skyroom lounge atop. But before any major structural changes could be embarked on, an early morning two-alarm fire swept through the inconvenient restaurant, destroying it.

But enough about Fairchild’s, so tasteful, so refined, and — save the unmistakeable possibility of it having been torched for the insurance money — so very, very boring. Let’s dig into the fascinating drama unfolding behind the scenes. For there would be no Fairchild’s without the Machris family. And the Machris family has tsuris.

On July 27, 1952 shortly after take off from Rio De Janeiro on a flight to Montevideo, the door of a four-engine Pan-Am stratocruiser aircraft blew off, and Mrs. Marie Elizabeth Machris Westbrook, 38, was sucked out of her window seat and cast into the Atlantic Ocean 12,000 feet below.

Seated beside her was the man who claimed to be her newlywed husband, Emilio Capellaro, a Roman banker. According to news reports, her mother Bessie Machris was aware that Marie, formerly divorced from U.S. Air Force Col. Robert B. Westbrook (a fighter pilot shot down over the Macassar Straight in 1944, his body never found) intended to marry Capellaro, but as of their last phone conversation just one day before the incident, thought that no such ceremony had taken place.

Capellaro said that he had been smoking when the door blew open with a loud explosive sound, and neither he nor any of the other 19 passengers or 7 crew members saw Marie, who had been taking photographs out the window just in front of the door, disappear. It was, supposedly, several minutes before anyone, including Capellaro, realized that she was gone. The plane returned to Rio, and despite a lengthy search by the Brazilian Air Force and the distribution of thousands of fliers by Machris family attorney Robert F. Tyler, no sign of the missing woman was ever found. Marie’s plan at the time of her death had been to fly back to Los Angeles, pick up her young son, then return with him to South America for an extended vacation.

In September 1952, Superior Judge Newcomb Condee declared Marie legally dead, and admitted her will to probate. It was reported that no evidence had been found to prove that Emilio Capellaro had been married to Marie at the time of her death. Her 1951 holograph will left the entirety of her $157,000 estate to her son Robert Machris Westbrook, then 12. In June 1953, Bessie accepted a $19,500 wrongful death settlement from Pan American Airways. As a condition of the settlement, Emilio Capellaro supplied a signed statement attesting that he had been engaged to Marie, but that they were not married.

Photo: L.A. Times

After several years engagement, Peter Fairchild married Katherine Machris in August 1954, and moved into the Machris home on Kings Road with Bessie and Katherine. Robert, Marie’s orphaned son, lived at boarding school in Palos Verdes. Bessie died in April 1955, leaving her estate in trust to Katherine and Robert. Bessie had been Robert’s legal guardian, so her death left the 15-year-old unmoored. Her will stated that in her absence, she wanted family attorney George W. Nix to be his guardian in tandem with Citizens National Trust & Savings Bank. Robert’s paternal grandparents also sought custody, claiming that they had been for some time denied the companionship of their grandson.

In August the interested parties appeared in Superior Judge Richards’ courtroom to plead their cases. Robert said that he had never known his father’s parents nor did he wish to know them, that his aunt Katherine was like a mother to him, and that he wanted her to be his guardian. Attorney Nix withdrew his petition for guardianship out of respect for the young man’s wishes. The judge determined that Katherine would be Robert’s personal guardian, while his grandfather acted as co-guardian with a bank over the youth’s then $7,500,000 estate.

In the early 1960s, Robert reached his majority and began receiving the principal of his significant inheritance. His 21st birthday party, at Romanoff’s, hosted by Peter Fairchild and aunt Katherine was capped by the arrival of a bank official, who presented the youth with a check for $1,000,000–the first installment of what was said to be a $50,0000,000 fortune. He had to borrow ten bucks from a party guest before the night was done.

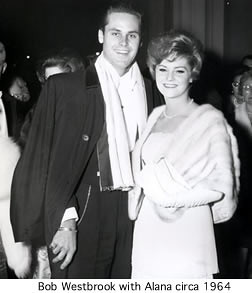

Rich, handsome and of age, Robert sought love, and was briefly married to redheaded Judi Meredith, called by one tabloid “the sexiest starlet in Hollywood” for her supposed effect on Frank Sinatra. She rejected the label, insisting that she was freckled, flat-chested and talented, and that she was going to stop dating actors in hopes of avoiding further tabloid attention. She was no happier with an oil heir.

Robert sued to annul the marriage, claiming he had believed Miss Meredith to be a virtuous woman saving herself for the man she loved, that he had since learned otherwise, and that they separated on December 11, 1960, the day of their Las Vegas marriage. Miss Meredith countered that they had been together through January 25, and that “outside influences” were conspiring to break up their happy home. She added that Robert beat her, but that she wanted him back. She asked L.A.’s Superior Court for help.

A March 1961 court order directed Robert’s aunt Katherine and her husband Peter Fairchild, apparently the “outside influences” to which Miss Meredith alluded, to attend a reconciliation hearing. It didn’t take. The marriage was annulled on grounds of non-consummation, and Miss Meredith received a settlement of $35,000, a car and a suite of bedroom furniture. She wept outside the courtroom when talking with news reporters, then worked through her grief by playing a sexy witch in the 1962 fantasy “Jack the Giant Killer.”

Robert meanwhile returned to the bosom of his family, then went to Europe to research Continental cuisine innovations to bring back to Fairchild’s, in which he now had an ownership stake.

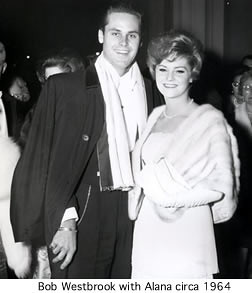

Robert was subsequently engaged to Alana Ladd, daughter of Alan Ladd and Sue Carol, but they never married. Their engagement was marked with drama: Alana saw Robert gored by a bull in Spain, and her mother was injured on Sunset Boulevard, when a street racer drove head first into Robert’s car, totaling it. Alana would marry British radio personality Michael Jackson, both remaining friendly with Robert.

Photo: MichaelJacksonTalkRadio.com

Relations between Robert Westbrook and Peter Fairchild would sour over the decades, and in a 1986 Superior Court lawsuit, Westbrook sought control of 40 acres of Palm Springs land held by Fairchild, alleging that Fairchild had been like a father to him, as well as his financial advisor, and that he had failed in both roles.

In 1970, they went into a partnership to acquire The Santa Barbara Inn, with Westbrook contributing all the cash, Fairchild receiving 50% interest in the property. Fairchild took substantial loans on the building, and after it was sold Westbrook contended that Fairchild’s significant profit should erase any previous financial agreements between the two. The trigger for the suit was Fairchild’s refusal to make good on his promise to make a will leaving everything to Westbrook. Westbrook tried to take control of the still-living Fairchild’s assets, but was unsuccessful. He did, however, win punitive damages in the amount of $200,000 and compensatory damages of $500,000. The court battle dragged on for years, and Peter Fairchild died in 1997 in Palm Springs, aged 83.

Robert Westbrook, whose childhood reads like a tragic fairytale, grew up and lost the fortune which had brought so many problems into his life. He told friends that he’d been swindled by his “uncle” Peter. And once all the money was gone, he found he had the blues–not depression, but a deep connection with the American musical vernacular. He played guitar and sang his way across the Los Angeles indie folk scene, and when he died in 2007, the occasion was marked with a beautiful eulogy. And Restaurant Row, a concept realized in part through the Wilshire Oil millions that were his inheritance, shines on.

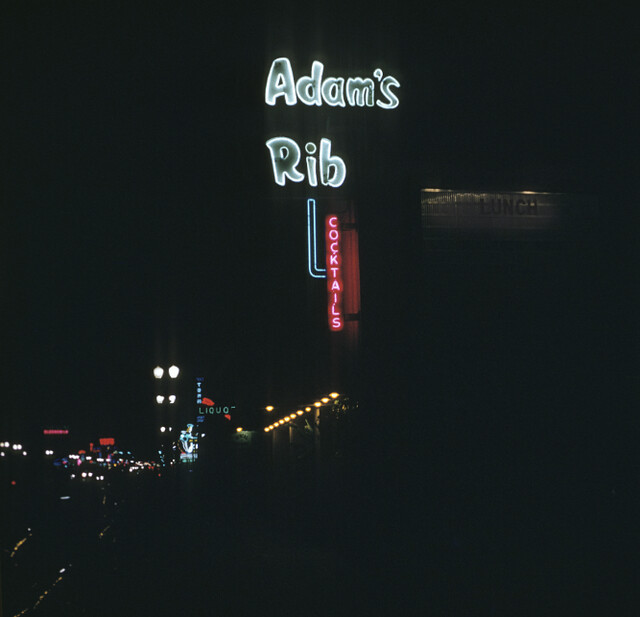

photo: George Mann

Finally, let’s veer away from the toxic glamour of Restaurant Row and settle in for a comforting bowl of something rich and sweet at the wacky old Wan-Q Chinese restaurant on Pico at Wooster, which survives today, stripped of its tiki splendor, but still dishing up egg rolls and fried rice and gracious service, under the name Fu’s Palace.

Photo: L.A. Times

The visionary behind Wan-Q’s Polynesian pop decor was restaurateur Benny Eng, who opened his restaurant in 1958, and circa 1960–around the time he claimed to have served his millionth customer, a achievement that seems to be a physical impossibility– transformed the squat, single-story brick building first with subtle Chinese patterned screens, and then into a fantastic piece of roadside exoticism, its modest corner entry enlivened with a striking, double-height thatched A-frame hung with fishing floats, batik wall treatments, ship’s wheels, bamboo faux “structural” elements and a massive leering tiki head sign with a stylized bone through its cheeks.

Above the doorway crouched a human-sized tiki blowing a raspberry and sporting an unmistakeable metal phallic protrusion. This figure may have proved too “interesting” for public consumption, as it doesn’t appear in renderings of the redesigned building on period matchbooks and menus.

photo: George Mann (detail)

Inside, generations of West LA families stopped “at the sign of the two torches” to enjoy Benny Eng’s celebrated hospitality, “Tropicocktails” in the waterfall-splashed Mauna Loa Room and “Chicago-style” Cantonese recipes rumored to have been passed down for thousands of years. The frequent redecoration schemes–five as of 1967– were a selling point, always promoted with the promise that despite the expense, meal prices remained affordable and ample parking free.

In February 1967, Wan-Q promoted a special Chinese New Year celebration, three days of feasting aimed at the Anglo families of cops, firemen, restaurant workers, cabbies, telephone operators and others who had to work through the Western New Years Eve.

Benny Eng apparently retired or fired his publicist in 1974, spelling an end to his entertaining mentions in the local press (Benny Eng loves pancakes! Benny Eng loves cheeseburgers! Benny Eng rescued members of his extended family from Red China–then served them cheeseburgers!). In 1982, one of the last LA Times clippings about the restaurant strangely promotes its “Beijing-style” cuisine, and before long, Wan-Q hung up its woks.

Briefly the Kon Tiki, by 1987, Wan-Q was known as the Sugar Shack aka Jack’s Sugar Shack, a Caribbean restaurant, tiki bar and roots music venue. When Jack’s relocated to Vine Street, they took many of the Polynesian fixtures with them, leaving a much diminished structure that is neither fish, nor fowl, nor tofu either. But if you’re stuck on the west side with a hankering for old school Americanized Chinese food, Fu’s Palace won’t disappoint.

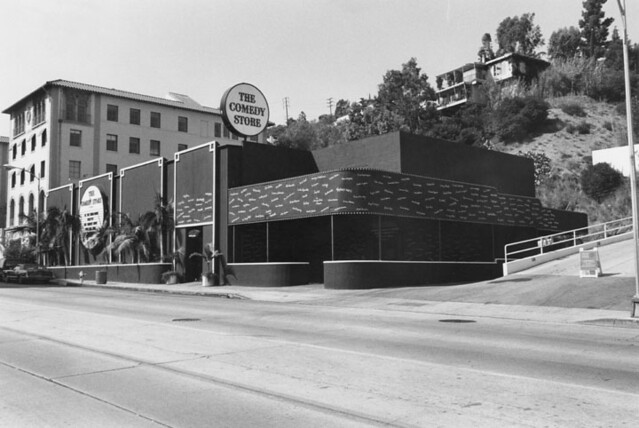

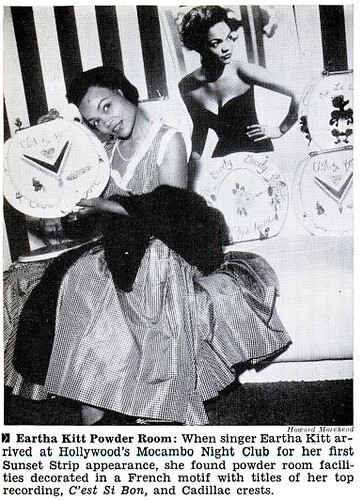

Thus ends today’s adventure in lost L.A. eateries. Stay tuned to On Bunker Hill for our next trip in the footsteps of photographer George Mann, when we’ll be featuring the glamorous dining options along the Sunset Strip, including what just might be the greatest forgotten large-scale figural neon sign in L.A. history.