Location: 230 South Olive Street

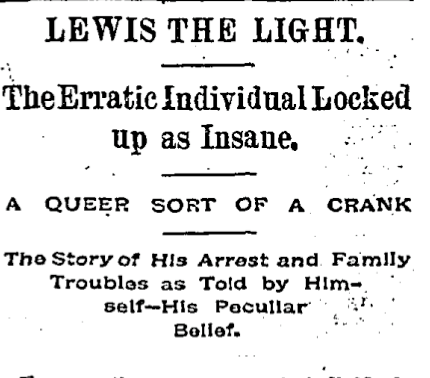

Louis Burgess Greenslade, a native of Devon, England and better known as Lewis, The Light, was already balmy in January 1889, when Doctors Field and Fitch of Bellevue Hospital sent him to the Hart Island asylum, off Manhattan.

He had been institutionalized after his neglected wife came from Pasadena in response to a letter from Louis stating that one of their sons, who was traveling with him, was dying. She sold everything she had to finance the trip, where she discovered her child was quite well, but Louis –not so much.

Some time later Louis left the asylum to rejoin his family in California, where he found his wife had died after telling neighbors she was a widow, and that his children had been put into public care. He moved to downtown Los Angeles, where he grew a long beard, dressed "in fantastic garb," declared himself a messiah and lived on the donations of true believers.

An investigation resulted in him being declared unfit to rear his daughter Calla Lily (aged 14 in 1891), and he went to court seeking her release, then tried to snatch her from Mrs. Watson’s Home. He was tried on grounds of insanity, but freed because the thrifty law required homicidal or suicidal tendencies if a madman was to be cared for in an asylum. He tried to make a speech to the court, was rebuffed, and in January 1892 was determined to be in fact dangerous and committed to the State Insane Asylum at Agnews (a village later absorbed by Santa Clara).

But by June he was reported to be handing out peculiar circulars outside Metropolitan Hall in San Francisco, and in October arrested in that city on a charge of having torched the Turnverein Hall. In April 1894 he was sent back to the asylum at Agnews, a place he claimed was ideal for "resting and fattening up." (Lucky Lewis was not at the trough in April 1906, when the institution collapsed in the great earthquake, killing 117 patients and staff. All were buried on the grounds, which now comprise the supposedly haunted Sun Microsystems campus.)

Satisfied with his care and the width of his belly, Lewis escaped and returned to San Francisco, where he was arrested after ripping open his clothing and asking passersby to witness the divine light that burned in his breast.

For the rest of 1894, through 1895, 1896 and 1897 there was no sign of Lewis the Light. But in January 1898 he made a triumphant return to Los Angeles, tossing down a hand-written message at the feet of the deaf-mute newsstand operator Max Cohn at 124 ½ South Spring Street.

"Max: Read this intelligently and with interest! Deaf mutes are caused by the unnatural crime of rebelling against Lewis the Light! All nature, together with humanity, groans for lack of using Lewis the Light! Whilst people are such unnatural fools as to breed mules, there will also be deaf mutes to suffer for it. Greater than the ram’s horn is the horn of the he-goat." LEWIS THE LIGHT

He was at this time living at 230 South Olive Street with two of his sons who worked as messengers and supported the family. By July 1898, the L.A. Times already sounded sick of him when reporting "Los Angeles is again afflicted with [his] prophecies."

Lewis the Light, you see, what a newspaper reader and a letter writer. He’d comb the papers for reports of some personal catastrophe, then send a note (or many notes) preaching doom and damnation to the unfortunate sufferer, with the promise that future traumas could be avoided if they could only consult him, and tithe accordingly. (That fire in San Francisco was just another subject that drew his interest, but only after the fact.) Hence in July ’98, E.T. Earl had to contend not only with the loss of his Wilshire boulevard home to fire, but with an original missive from Lewis, The Light:

"Armageddon, allegorically and literally. Now Earl: count yourself as having been subjected to one variety, at least of Fire, and liable to many others through utterly failing to do your duty in personally and practically recognizing and rendering his due to the Lord of Life. Deut. 3-15, 32-22."

The message was signed with a rubber stamp showing a horse and an invitation to visit "Lewis, the Light, accident preventer" at this address. Mr. Earl called the cops, and Louis was warned to knock off with the nasty notes (particularly the letters to women, which were especially racy) or he’d be shipped back to the bug house. A record was made of his business card, which read, "Accident preventer, central civilizer, longevity promoter; subject to nothing; terms a tithe."

In May 1899, one of Louis’ sons, his 22-year-old namesake, flipped out after reading too deeply in the scientific section of the public library. The young man, who fancied himself an inventor, went into the basement offices of his employers, the California District messenger service beneath the Los Angeles National Bank and began smashing windows, furnishings and bicycles. He was subdued and taken to the County Hospital, where he raved he had "been doped." Facing the judge, young Louis frothed maniacally and tore at his chains while the father calmly answered questions about his son’s mental state. The boy was committed to the Highland asylum after becoming so unruly he had to be removed from the courtroom.

On March 2, 1901, at 2pm, there was a conflict in Central Park (now Pershing Square), when Lewis the Light’s prediction of the second coming of Christ was scheduled for the same hour as a concert by the Catalina Marine Band. This disrespect so incensed Lewis that J.M. Garrison, the park foreman, called for police protection at the holy hour. According to a petition then circulating (with 800 signatures to date), the park had become something of an eyesore due to the "[infestation of] loafers an bums to such an extent that its usefulness to the populace as an airing-place is destroyed."

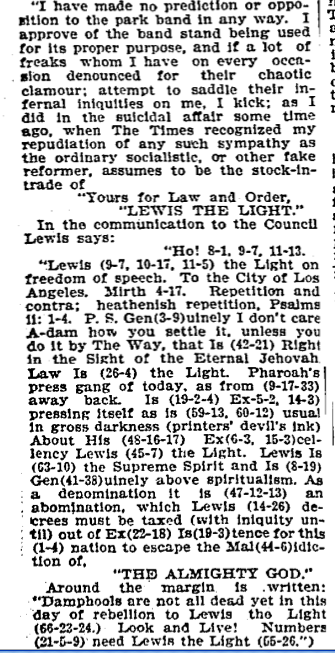

The petition read: "We, the undersigned, residents of Los Angeles, respectfully petition that legal means be employed to abate the public nuisance of the large gathering of men and boys daily in the band stand at Central Park. We are persuaded that the public haranguing at the park destroys the attractiveness of the place, interferes with the rights of the public, and exercises an immoral influence, especially upon the young boys, whose minds are constantly filled with false views of nature and of life. Much of the talk at the band stand we believe to be blasphemous, although a few conscientious men do endeavor daily to antidote this poison, we believe their efforts are in the main futile, and we believe its abatement a great necessity." It was filed in city council, alongside a contrasting petition presented by John Murray, Junior of the Socialist Democratic Party, in support of free speech. And of course, Lewis the Light had an opinion about the matter.

As could be expected, the September 1901 assassination of President William McKinley drew the attention of Lewis the Light (then age 49), and after he penned some of his typical missives (signed "Umbilical Cord of the Universe, Potentate of Prosperity") convinced the Eastern recipients that he was a dangerous anarchist. Local detectives knew him as a harmless crank, but nonetheless took him into custody as a courtesy to their colleagues in the east. Arrested at his Olive Street abode, Louis snapped "You can’t do me any harm, for I am Jesus Christ." In court he proclaimed his opposition to anarchy, and claimed he was the only person to speak out against Red Emma Goldman during her visit to Los Angeles. Unimpressed, Judge Shaw proclaimed him insane

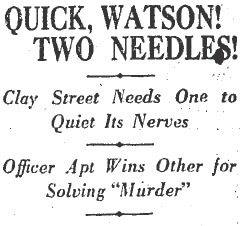

In 1907, Lewis the Light crossed paths with author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who inquired with Los Angeles police about some mysterious letters sent in his care to George Edalji, whose conviction false on charges of animal cruelty Doyle helped eradicate via a most Holmesian investigation. The Edalji family’s troubles had begun with anonymous letters, but local police were able to soothe their concerns when they assured Doyle that neither their local crank nor his recent roommate Frank Sharp had anything but an idle interest in their affairs. One side effect of Doyle’s interest was the discovery that Louis Greenslade had left England after annoying a Sir Henry Knight with weird letters.

In 1908, Lewis the Light was charged with vagrancy and sentenced to thirty days after annoying citizens who he threatened should they refuse to pay a tithe. This would be the last appearance of this colorful character in the pages of the L.A. Times, and before long, his name, once an object of glee and fascination, sank into obscurity.

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres,

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres,  Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition.

Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition. And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?)

And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?) Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

And the downtown Los Angeles of today came through the quake swimmingly, with the most significant damage being sustained by the Literature & Fiction Department at Central Library, which was briefly closed this afternoon after many of its books were flung from the shelves by tremors.

And the downtown Los Angeles of today came through the quake swimmingly, with the most significant damage being sustained by the Literature & Fiction Department at Central Library, which was briefly closed this afternoon after many of its books were flung from the shelves by tremors. Nearby, witnesses watched in horror as the tops of the Federal Building, the Hall of Justice, and City Hall swayed visibly, and the screams of prisoners being held on the top three floors of the Hall of Justice could be heard from the street below: "We want out! We want out!"

Nearby, witnesses watched in horror as the tops of the Federal Building, the Hall of Justice, and City Hall swayed visibly, and the screams of prisoners being held on the top three floors of the Hall of Justice could be heard from the street below: "We want out! We want out!"

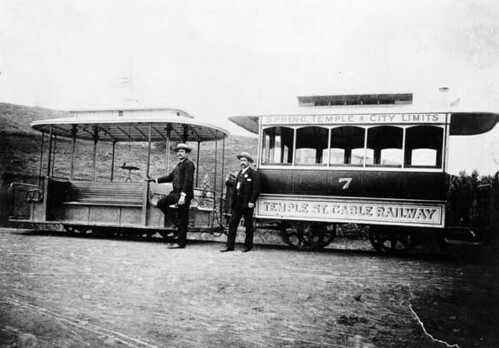

Bunker Hill was the first grand Los Angeles neighborhood to flourish outside the bright and dusty Plaza. It was home to the city”™s finest families, who built exquisite gingerbread houses with hillside gardens that reflected their wealth and taste. A jaunty funicular delivered residents into the midst of downtown”™s commercial center. It was the pride of the west.

Bunker Hill was the first grand Los Angeles neighborhood to flourish outside the bright and dusty Plaza. It was home to the city”™s finest families, who built exquisite gingerbread houses with hillside gardens that reflected their wealth and taste. A jaunty funicular delivered residents into the midst of downtown”™s commercial center. It was the pride of the west.