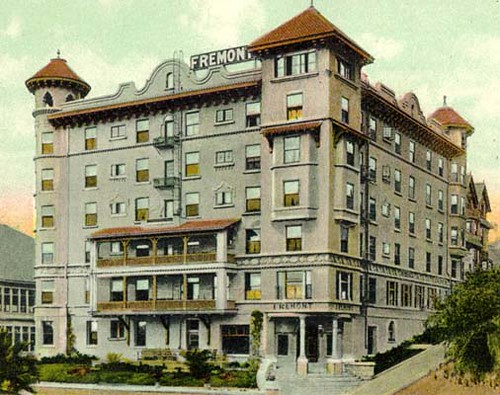

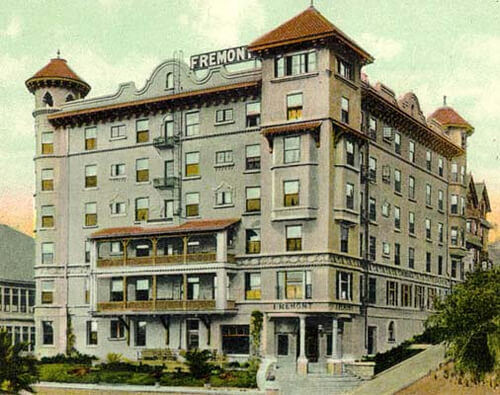

The Fremont Hotel that stood on the corner of 4th Street and Olive for five decades had 100 rooms. As previous posts on this site have shown us, no place on Bunker Hill with a lot of rooms and a long lifespan existed without a good amount mayhem. The Fremont is no exception.

The Fremont Hotel went up in 1902 and was designed by John C. Austin, who would later make a permanent mark on Los Angeles by co-creating City Hall, the Shrine Auditorium, and the Griffith Observatory. Plans for the ritzy new hotel were announced in November of 1901, and other than a brief skirmish with the neighboring Olive Street School over the erection of a retaining wall, construction went smoothly. The Mission style building opened its doors to the public in September 1902.

With so many residents floating in and out of the Fremont, it should come as no surprise that a few guests checked in and never checked out. Many residents who called the Fremont their final home were quite prominent. For example, Dr. Edwin West was a retired New York physician who settled in California when he found true love at age 79 and married his thirty-something paramour. It was the new Mrs. West who cared for the doc until he succumbed to illness in his room at the Fremont, and probably inherited his fortune. Then there was Harry Gillig, member of pioneering California family who was stricken down by a heart attack in 1909. Gillig was a onetime bridegroom of Amy Crocker, who we have heard about before. Finally, D.W. Kirkland, founded of the Owl Drug Company, lost a battle with pneumonia at the Fremont in 1915.

Final exits at the Fremont were not always so peaceful. The note in N.H. Cummings’ pocket indicated he was suffering from ill health, which is why the Fremont resident jumped from a rowboat into MacArthur Park lake and drowned. Financial troubles caused oilman William W. Stabler to put a bullet through his heart. His wife discovered him in the office he kept at the hotel. In 1952 when John Swiston’s horse betting system failed him, he went to Lincoln Park and slit his wrists. He survived, and was able to returned to his room at the Fremont Hotel, and probably the horse track.

It wasn’t all about death at the Fremont Hotel. There was also robbery, domestic disputes, arson, and much, much, more. After J.W. Aaron was arrested for public drunkenness in 1903, the police soon discovered that he was also the burglar who broke into Marie Kinney’s room at the Fremont and stole her opera glasses. The judge did not buy Aaron’s story that the glasses

were lent to him, and Aaron was held on $1,500 bail.

Next, we have Mr. & Mrs. Griffith, who were married in 1887 and spent the next 16 years occasionally threatening to murder each other. In May of 1903, Mr. Griffth allegedly held his wife at gunpoint in their Fremont room and the ensuing scuffle was broken up by an unannounced visit from their son. Four months later at a hotel in Santa Monica, Mr. Griffith went through with the dirty deed and shot the missus in the head. She responded by physically attacking him before jumping out an open window. Mrs. Griffith lived to tell her tale, and file for divorce. Col Griffith J. Griffith spent two years in San Quentin, having been convicted of attempted murder brought on by alcoholic insanity. Back in 1896, Griffith had donated 3,015 acres of land to the City of Los Angeles. In 1913, he set up a trust fund to construct a couple of structures on the land. The land and buildings are Griffith Park, the Griffith Observatory, and the Greek Theater.

The Fremont narrowly escaped a blaze when arsonist, George L. Gould was caught trying to set the place on fire. Police believed the 23 year old Gould to be the source of 20 fires started in the Dowtown area.

One of the more bizarre incidents at the Fremont occurred in March of 1927 when George W. Fellows was arrested for broadcasting a radio program from his room. The problem was not the content of his show, but rather the length of the waves he was using to broadcast it, which exceeded regulations. Fellows responded to the charges by fainting in court.

While the residents of the Fremont Hotel added a great deal of color to the goings on in the building, they pale in comparison to the employees. We’ll save their sordid tales for a future post…

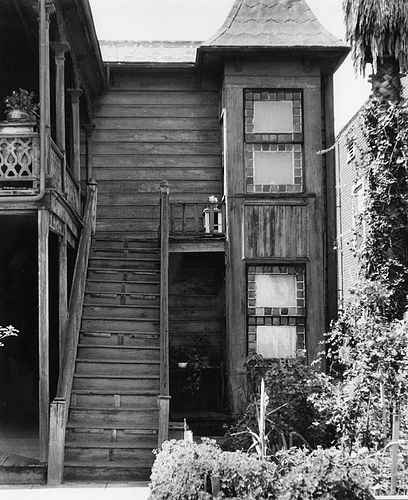

Photo courtesy of the USC Digital Archive

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

Say “mother fixation” and dollars to donuts you mean, or are taken to mean, a fixation on your mother. Mrs. Emma Rupe was fixated on being a mother. So much so that on July 5, 1936, the Denver waitress took a fancy to John, the two year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. John Richard O‘Brien. John, it seems, looked just like Emma‘s own toddler who‘d died nine years previous. On the pretext that she was going to take the little darling out to buy him a playsuit (the O‘Briens being trusting souls, and near penniless, so how could they refuse?) Emma thereupon took John shopping”¦as far from Denver as she could get, and with as great a chance of disappearing as possible. Because clichés are born of truth, noir clichés especially, she beelined straight for Los Angeles, Bunker Hill specifically, and checked into the St. Regis.

Say “mother fixation” and dollars to donuts you mean, or are taken to mean, a fixation on your mother. Mrs. Emma Rupe was fixated on being a mother. So much so that on July 5, 1936, the Denver waitress took a fancy to John, the two year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. John Richard O‘Brien. John, it seems, looked just like Emma‘s own toddler who‘d died nine years previous. On the pretext that she was going to take the little darling out to buy him a playsuit (the O‘Briens being trusting souls, and near penniless, so how could they refuse?) Emma thereupon took John shopping”¦as far from Denver as she could get, and with as great a chance of disappearing as possible. Because clichés are born of truth, noir clichés especially, she beelined straight for Los Angeles, Bunker Hill specifically, and checked into the St. Regis.

The early 1960s were no more kind to this little niche of the Hill than any other. The Bozwell Apartments (which seem to shoot for Greek Revival but, oddly, come off as Monterrey) next door at 245, abandoned, burn on May 22, 1962.

The early 1960s were no more kind to this little niche of the Hill than any other. The Bozwell Apartments (which seem to shoot for Greek Revival but, oddly, come off as Monterrey) next door at 245, abandoned, burn on May 22, 1962.

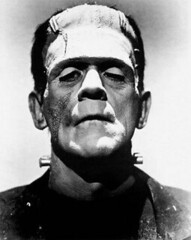

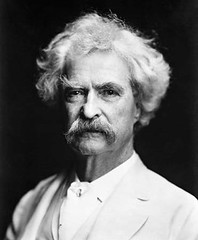

Then came the biggest shock of all ”“ he found that he”™d been reported dead!

Then came the biggest shock of all ”“ he found that he”™d been reported dead! her spouse”™s unprecedented resurrection. Perhaps it was the strain of being constantly on the lookout for torch-wielding villagers.

her spouse”™s unprecedented resurrection. Perhaps it was the strain of being constantly on the lookout for torch-wielding villagers.