In the first installment of our series on George Mann’s newly-discovered vintage Los Angeles restaurant photos, we introduced you to Mann’s custom 3-D photo viewer, which provided free entertainment to patrons as they waited to be seated in numerous L.A. restaurants, and to images of the Malibu restaurants that were displayed inside the viewers. In the second entry in the series, we toured the Bixby Knolls neighborhood of Long Beach, home of some gorgeous, long-demolished restaurants–and a surprising survivor. And last time we got together, we took a trip to the dark side of life along the celebrated Restaurant Row, La Cienega Boulevard.

Today, our travels with George take us to the top of La Cienega and then deep into the Sunset Strip, to see what’s cooking along that fabulous boulevard, which for close to a century has been the preferred promenade for movie stars, gangsters, star makers and the normal folks who love to look at them. Let’s see which Sunset Strip establishments caught George Mann’s discerning eye.

photo: George Mann

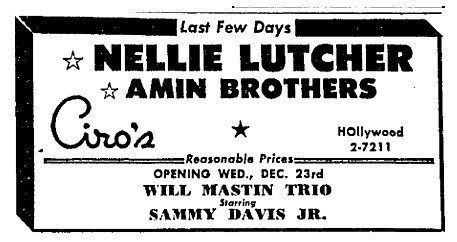

We begin at the Marquis Restaurant, at the intersection of Sunset and Roxbury. The space is perhaps best remembered as the Mexican club/restaurant Carlos & Charlie’s, which in its final years had a reputation for rowdiness. Later it was Dublin’s Irish Pub, and it’s presently something called Sunset Beach that looks like a bunch of tipsy white sails unfurling around popsicle sticks.

photo: George Mann

But from the mid-1940s through the early 1970s, this was The Marquis, sometimes known as Paul Verlengia’s Marquis, after its opera-singing host.

George Mann’s photo captures the restaurant soon after its 1953 remodel, a low-slung brick and half-timbered structure with the look of a country house converted to trade.

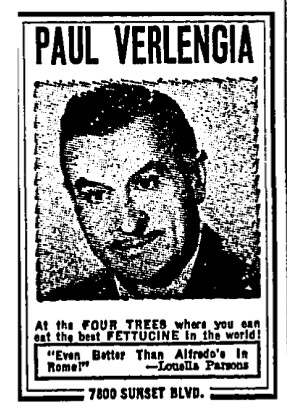

The interior was similarly homey and understated, and must have been a welcome respite from the self-consciously modernist glamour of so many Sunset Strip establishments. But while the Marquis looked sleepy, dinner was still served until the wee hours, with Chef Pietro Giordano whipping out platters of his famous Zucchini Florentine (“better than that at Alfredo’s in Rome!” – Louella Parsons), a sort of crustless quiche, on demand.

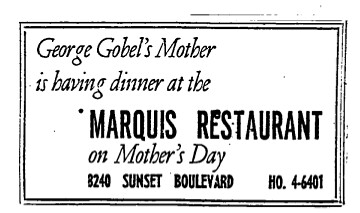

It was in this pleasant space that comic George Gobel not only dined with his mama on Mother’s Day 1955, but advertised the fact, in advance, in the Los Angeles Times. Now why don’t TV stars do that sort of thing any more?

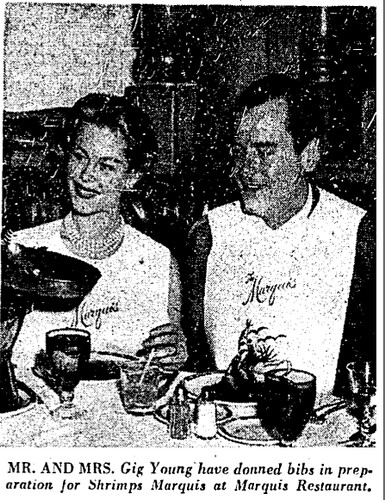

It was here, too, that actor Gig Young and his bride Elizabeth Montgomery strapped on their bibs and shared a piping dish of Shrimps Marquis in 1959. A few years later, Gig might have taken his new wife Elaine Young up to the Oak Barrel Bar to dig the swinging sounds of the Sam Ray Trio, or enjoyed strolling musicians in The White and Marquesa Rooms.

photo: Los Angeles Times

In spring 1960, Paul Verlengia opened another restaurant just four blocks east, the Four Trees. He took Louella Parsons’ quote with him.

The Marquis sailed on sans Verlengia, and into a tragedy. On February 8, 1963, the restaurant’s corporation president George Dolenz (dad of future Monkee Mickey and himself star of TV’s Count of Monte Christo), climbed onto the roof of the Marquis to inspect recent construction. He suffered a heart attack, was brought down by firemen, and was declared dead on arrival at Citizens Emergency Hospital. Since 1951, Dolenz’ main focus had been the restaurant. He was just 55.

In 1965, owner Tom Seward started keeping lunch hours, and coined the gracious if not too memorable slogan “A good place for business or pleasure. Our surroundings take the busy out of business.”

When local restaurant owners from the Sunset Strip Association met in November 1966 to voice their concerns about ongoing teenage protests of new curfews on the boulevard, they chose the Marquis for their press conference. Fred Rosenberg, president of the association, blamed police and newspapers for exacerbating the problem. Outside, teens protested, perhaps confusing this relatively liberal business group with the far crankier Sunset Plaza Association headquartered some blocks west.

By 1970, the Marquis was reinvented as the Martoni Marquis, under the management of famed restaurateur Mario Marino. Sonny Bono was goo goo for his clams. And sometime in the mid-1970s, the Marquis quietly faded away.

photo: George Mann

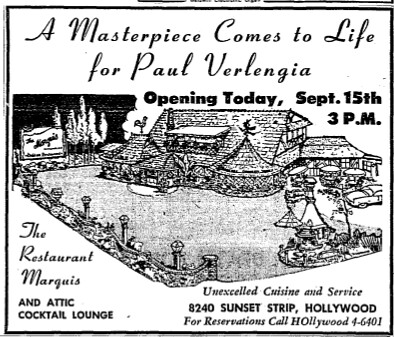

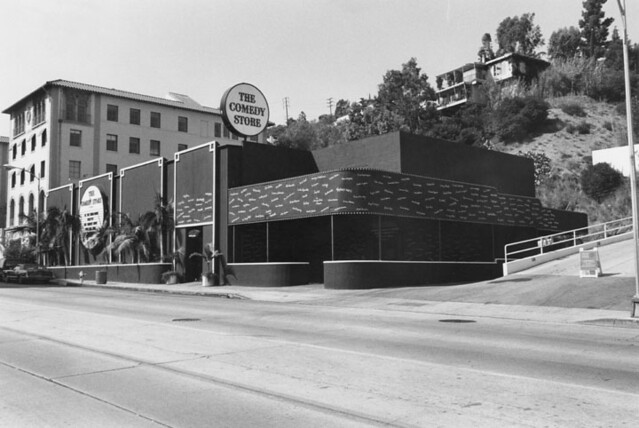

Heading west into the Strip proper, we come to Ciro’s, which lives on today as the Comedy Store. In the mid-1960s, the nightclub played host to rousing sets by folk-rock crossover act The Byrds, whose fame was cemented when Bob Dylan dropped by to whale on the harmonica. But this 1950s-era night time shot shows a pre-pop Ciro’s, and a more interesting use of the building than has been made in decades.

photo: Los Angeles Public Library

The biggest difference between George Mann’s photo and the current design is how the entire building is used to imaginatively sell the venue and its performers. Today it’s simply a black box covered with faux celebrity signatures, but the place was designed to tell a more complicated and attractive story.

Just look at how much is going on, without any sense of clutter. There’s an understated neon CIRO’S script on the roof, a rosy spot-lit CIRO’S script on the street-facing curtain wall, a bright neon CIRO’S looking onto the driveway, a spot-lit banner advertising CIRO’S FUN FESTIVAL on the small projecting second story cube–all framing a row of soft lights welcoming celebrants into the exciting zone within.

And that, friends, is the difference between signage designed by an architect and signage designed by the guy who paints the sign.

photo: George Mann

George couldn’t have picked a more iconic night to shoot Herman Hover’s Ciro’s than one when the marquee welcomed the Will Mastin Trio starring Sammy Davis, Jr.

For Ciro’s on the Strip is where the 25-year-old Sammy became a star in March 1951, and forever eclipsed his father and “uncle” Mastin–not to mention the venue’s nominal headliner, Janis Paige, who graciously, and wisely, insisted on taking the opening slot for the remainder of the booking after seeing what Sammy was capable of.

But Sammy never forgot his roots, and despite his solo fame, he often performed with his old partners. The three men are buried in adjacent plots in Forest Lawn – Glendale.

But Sammy played Ciro’s with the Mastin Trio several times. So when was this photo taken? It’s not just the kid’s name on the marquee that tells us this photo wasn’t taken during Sammy’s star-making debut engagement. On the opposite side of the strip we see a trio of ground-mounted billboards flanking a double globe street light. These sit on the piece of land now occupied by the Mondrian Hotel.

photo: George Mann (detail)

The billboards advertise, from left to right: Ballantine Ale, the Bob Hope film “Here Come The Girls,” and Goebel 22 beer. The Technicolor-drenched “Here Come The Girls” was released in late October 1953. And sure enough, just in time for Christmas 1953:

So what could the SRO, celebrity-packed Ciro’s audience expect from the Will Mastin Trio with Sammy Davis, Jr.? While we weren’t able to find reviews of the 1953 performance, we did find a Billboard notice of the group’s August 1955 appearance at the club.

In it, Joel Friedman raves: “In the idiom of the trade, [Davis] gassed ’em”¦ Davis devoted the lion’s share of his hour and a half turn to his relatively new career as a pop singer”¦ He could have continued for another hour and still had the audience cheering for him. Tho such uninhibited thunder is generally reserved for the ballpark, Davis had it at Ciro’s opening night.” Friedman also praised Davis’ musical impressions of Nat “King” Cole, Mel Torme, Tony Bennett and Frankie Laine, his comic ripostes to famous audience members, and naturally his dancing.

This clip from the Milton Berle show gives an idea of the trio’s Sammy-centered variety act of the mid-’50s.

But to see the kind of electrifying dance action that made Sammy Davis, Jr. the unbridled sensation of the Sunset Strip, just clear your mind of all distractions, click below, and don’t forget to breathe:

As for Ciro’s, its smoothly moderne exterior (1940) was the work of architect George Vernon Russell, later hired by club founder Billy Wilkerson to craft the look of the Flamingo Casino (1945). The interior decoration, early Hollywood Regency heavy on the swag curtains and gilded putti, was by Tom Douglas.

Today, the club grinds along as The Comedy Store, successful at what it does, but with far less architectural panache. We’re hopeful that one day it will be restored to its original luster. If the owners want some inspiration, they need only consult George’s lovely 1953 photographs.

photo: George Mann

Continuing west along the boulevard, we come to Charlie Morrison’s Mocambo club, that legendary hotbed of musical race mixing. George Mann liked it so much, he photographed it on two occasions. This moody shot seems to capture the scene just as dusk falls. The neon and bulb signs are already flashing, awaiting the coming of darkness and the music-hungry hoards.

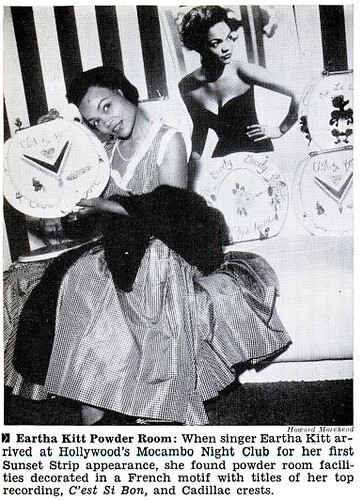

photo: Jet Magazine, November 26, 1953

In late November 1953, our marquee star Eartha Kitt made her first appearance on the Sunset Strip in an extended, sold-out Mocambo booking backed by the Paul Herbert Orchestra. Thanks to Billboard’s thoroughness, we know that the gig had a $2 cover, 230 person capacity, and shows at 10:30pm and 12:30am, with a third show added due to the huge demand.

Miss Kitt was riding high on her first wave of suggestive hits, “Santa Baby,” “C’est Si Bon” and “I Want To Be Evil.” After just two nights, Billboard predicted a smash for the girl “who sings like Marilyn Monroe walks.” Before the engagement was up, she was booked to play the Sahara Casino in Las Vegas at four times her Mocambo salary.

photo: Jet Magazine, December 3, 1953

A star-making booking, to be sure. Still, Los Angeles Mayor Poulson is said to have flipped his wig over Kitt’s “too sexy” performance before the King and Queen of Greece. Reached in Texas, Her Highness said she found the show “lovely” — but what can you expect from foreigners?

Of her 1953 appearance at the Mocambo, Billboard‘s Bob Spielman cooed: “The theme of Miss Kitt is sex, and you don’t have to spell it backwards for people over 35 to know what it is. Endowed with beautiful features, excellent figure and good voice, Miss Kitt conjures a sort of psychoanalytic vision on the stage, something that every man wants but can’t have because you know it isn’t real”¦ In the final analysis, tho, as she hisses about the stage, one isn’t quite sure whether the hiss is that of a cobra poised to strike, or merely steam escaping from an overheated radiator.”

photo: George Mann

George seems to have returned to the Mocambo to get a proper shot of the neon at night. Dancer Billy Daniel and Lita Baron (Mrs. Rory Calhoun) played several engagements at the club in the early ’50s, but we’re guessing George visited in January 1954, having decided his daylight view from late ’53 didn’t quite capture the scene.

Daniel and Baron didn’t quite capture the scene, either: their song and dance routines paled in comparison to the departed sensation that was Miss Kitt, with Billboard opining they were “dull, altho eye-appealing.” At the Mocambo just a few months pre-Kitt they’d been heralded as “the outstanding new terp-song act of the year.” Ouch. A few months later, Lita Baron left the act. Marriage (a rocky one) to a movie star seems to have required her full attention.

We appreciate the details captured in George’s rare daylight shot. Note the signature logo planters flanking the entryway.

photo: George Mann (detail)

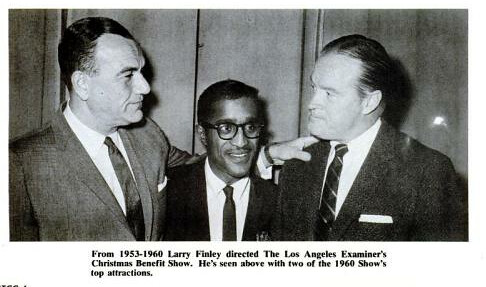

Note, too, that the famed nightclub shared its premises with a forgotten colleague, the namesake restaurant and cocktail bar of KFWB DJ / record exec / audio tape entrepreneur / anti-trust activist (he took on “octopus” talent agency MCA and won in 1945) / marketing whiz Larry Finley.

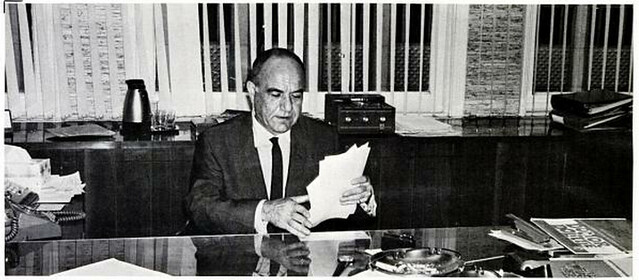

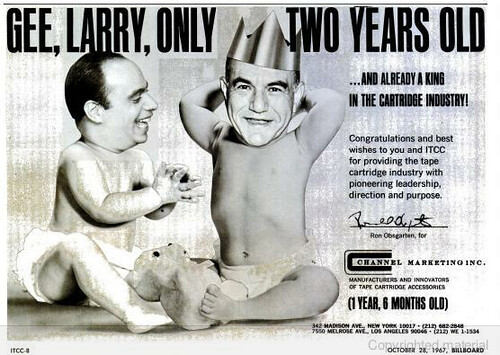

photo: Billboard Magazine, 1968

Finley (“the voice with a smile”) broadcast his popular radio show from the restaurant. The venue was sometimes called Larry Finley’s M.O.P. (for My Own Place) and stayed open until 4am–which just happened to be when the six-hour Larry Finley Time show signed off the air.

photo: Billboard Magazine, 1966

Larry Finley–and if you’re wondering where an Irish kid found all that chutzpah and energy, you won’t be surprised to know he was born Lawrence Finkelstein–died in 2000, aged 87.

photo: Billboard Magazine, October 28, 1967

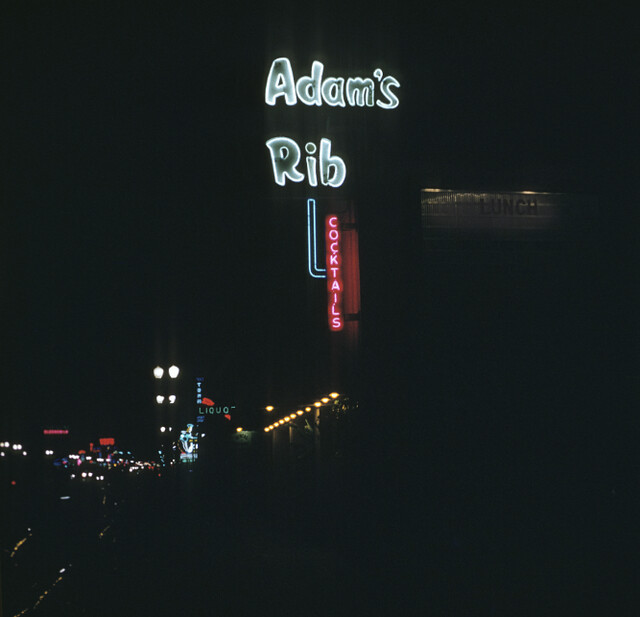

Continuing westward, we come to a forgotten cocktail bar sporting a rather jazzy neon font, Adam’s Rib.

photo: George Mann

While the address of this place eludes us, the identifiable neon in the distance situates the bar somewhere in the vicinity of Sunset and Sherbourne.

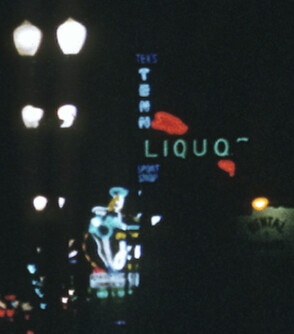

photo: George Mann (detail)

Adam’s Rib is a truly remarkable place: a Sunset Strip nightspot that never made it into the papers. It must have been truly wild to slip so far under the radar.

But about those hints of neon in the distance. Look closer. Could that possibly be a blonde carhop in a tiny skirt, bending over as she delivers her tray?

A hitherto unknown figural neon sign of astonishing erotic and artistic accomplishment?

It’s true. And this photo just may represent the most incredible discovery to come out of this series of rediscovered restaurant photos of the 1950s and 1960s.

Meet Miss Jackburger. Isn’t she lovely?

The long, narrow site which for many years was home to Tower Records has had other tenants, each one symbolising the vanguard of California culture. In 1944 it was one of several Dolores’ Drive-Ins in the Southland. By 1952, it was Jack’s Drive-Ins [the plural is sic], home of the “Big” Jackburger, and this remarkable polyglot sign comprised of sculpted backlit plastic, sinuous neon tubing and incandescent lights.

photo: George Mann (detail)

Despite the awesome signage, Jack’s on the Strip didn’t last long; by the early 1960s, the site was home to an Earl “Madman” Muntz Stereo-Pak shop installing early car stereos, and by 1970 it was Tower Records. In 2006, Tower’s bankruptcy spelled the end of this pop landmark and the start of an ongoing preservation crisis.

The signature Jack’s is similar enough to Jack’s at the Beach (see our Malibu post) for us to wonder about a business relationship with Jack Compselides’ beachside establishment, yet different enough for us to think “well, there aren’t THAT many ways to spell JACK’S in neon.”

photo: George Mann (detail)

We’d almost suspect the whole thing was a figment of our (admittedly fevered) imagination if it weren’t for one brief 1952 mention in the L.A. Times, proving that Jack’s actually existed.

So essentially, Jack’s Drive-Ins is a mystery, and aside from George Mann, nobody seems to have photographed its incredibly sexy sign. We owe him an enormous debt for having done so. Here’s to you, Mr. Mann!

photo: George Mann

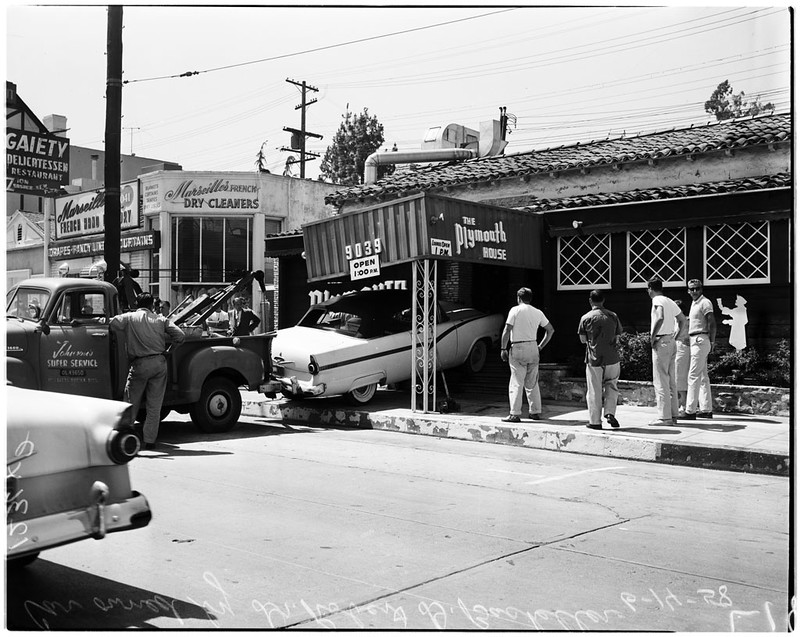

And finally, down towards the end of the Strip, we come to The Plymouth House, which was previously The Deauville, which the Times described as a “pink-walled retreat for stay-up-laters.” The Plymouth House opened in February 1953, featuring an English tavern style interior and Continental/Italian cuisine.

George and Gracie Burns celebrated their 37th anniversary with a dinner in February 1963, and in August 1962 the William Powells hosted a party for guests from San Antonio. Then there was one guest who dropped in a little unexpectedly.

photo: USC Digital Library

In later years the site was home to Gazarri’s, which became ground zero for hair metal culture in the 1980s, and it is presently The Key Club, and our final stop in George Mann’s Sunset Strip tour.

Stay tuned to On Bunker Hill for our next trip in the footsteps of photographer George Mann, when we’ll be featuring the forgotten steakhouses, sports bars and pancake houses of West Los Angeles. Till then!

I have a question about the Jack’s Hamburger sign…I found a photo of Jack’s place on Sunset Blvd. and the neon sign out front isn’t like the one you have posted for the location. Wondering if the sign was changed or from a different place? Here’s the link:

http://media.gettyimages.com/photos/photo-of-hollywood-and-sunset-boulevard-and-50s-style-and-sunset-picture-id86238100

What an interesting find! That half-rounded building shows its origins as a Simon’s Drive-In. I’m not good at dating cars, which might help in figuring out when this image was shot, but I believe the waitress neon shot by George Mann was on a much taller pole. So maybe both signs existed at the same time–but given the choice, who wouldn’t shoot the waitress?

Jack’s was owned by Jack D. Crouch – Wikipedia.