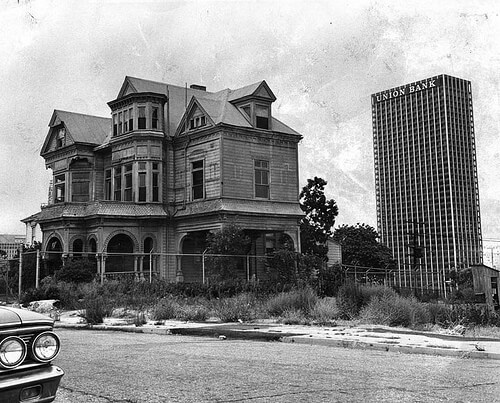

The most haunting image of old Bunker Hill’s final days depicts a fenced off Victorian mansion awaiting its doom with “progress” looming in the background in the form of the Downtown’s first skyscraper, the Union Bank Building. The residence, affectionately known for years as “the Castle” and located at 325 S. Bunker Hill Avenue, was one of two residences on the Hill to escape the wrecking ball, only to meet an even more tragic end.

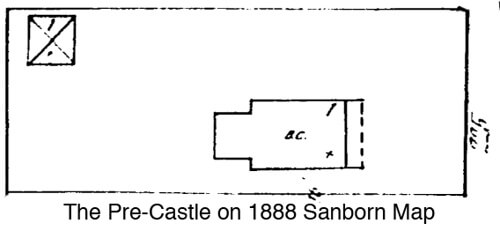

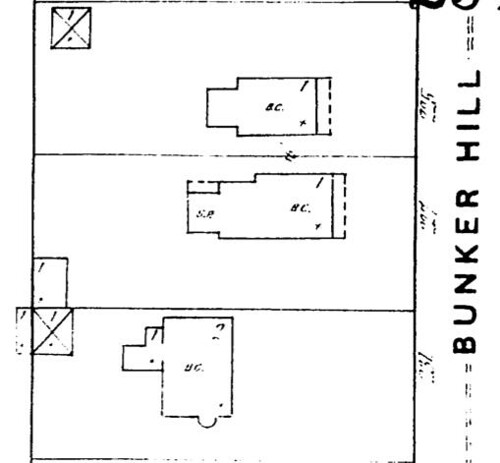

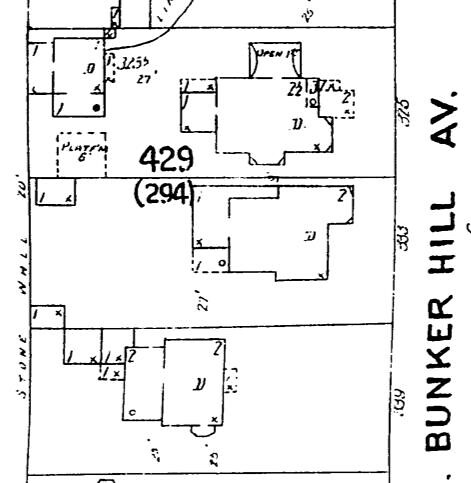

Located on Lot 16, Block L of the Mott Tract, early owners of the property were tee-totaling Los Angeles pioneer Virginia Davis and her husband John W., who sold the land for $450 to G.D. Witherell in March of 1882. It has long been believed that the Castle was built around this time, but an 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map reveals the structure as being constructed. In 1887 the property changed hands again, so it probably was capitalist Reuben M. Baker who built the large Victorian structure that would be a mainstay on Bunker Hill for over 70 years.

Designed in the Queen Anne style, the residence had 20 rooms, both a marble and a tile fireplace, and a three story staircase winding up the center of the house. Two of the mansion’s most recognizable features were the stained-glass front door and an overhang on the north side for carriages to pass through to the rear of the property. The curved Mansard roof on the tower and the triangular crown of a front balcony were removed after sustaining damage in the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. The original address of the home was actually 225 S. Bunker Hill Avenue until an ordinance, passed in December 1889, changed street numbering throughout the City, much to the irritation of many an Angeleno.

In March of 1894, grading contractor Daniel F. Donegan purchased the property for $10,500 and moved in with his wife Helen and four children. Though the family lived there for less than ten years, the name Donegan became the one most associated with the house and it has long been believed that the clan were the ones who nicknamed the mansion “the Castle.” A piece of neighborhood lore involved Donegan attempting to clear a nearby rat infested property by offering local children 25 cents for each cat brought to him, to be used as four footed exterminators. Residents were soon irked when their feline pets began to disappear. By 1902, the Donegans had moved, and new owner Colton Russell soon converted the mansion into a boarding house, a role the Castle would play for the next six decades.

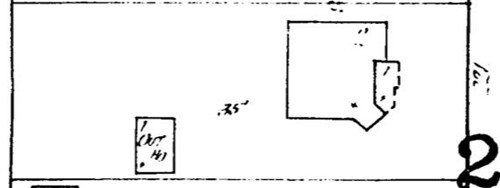

During its 60-plus year tenure as a multi-unit residence, the Castle would play host to all walks of life of the City of Angeles. Salesmen, doctors, waiters, elevator operators, miners, firemen, tailors, printers, hotel food checkers (well maybe just one of those), and many others called the Castle home at some point in their lives. When the WPA conducted a census of the area in 1939, 325 S. Bunker Hill Avenue was comprised of fifteen separate units, including a small guest house, built in 1927. The landlord’s family resided in four rooms while the rest of the tenants occupied single rooms and shared six toilets. The majority of the occupants were single, white and over 65 years of age. Rent ranged from $10 to $15 a month and occupancy at the Castle was anywhere from six months to eight years.

What the 1939 census failed to mention, however, was the Castle’s resident ghost.

The spook who haunted the Castle could possibly have been a former resident who met their ultimate doom in the mansion. In 1914 Hazel Harding, a 28 year old former school teacher with a history of mental problems, lit herself on fire and jumped out a second story window. She survived the fall, but succumbed to her burns. In December 1928, 66 year Charles Merrifeld shot himself to death with a revolver in one of the rooms. Merrifeld, who committed suicide to escape the effects of poor health, had been the Castle’s landlord with his wife Bertha since 1919. The Widow Merrifeld would continue to oversee, what she advertised as, the Castle Rooms for an additional eight years following her husband’s death. According to residents interviewed for a 1965 Herald Examiner piece, for years the ghost contented himself with one type of action; “Everytime one of the sculptured wooden decorations falls off the wall, Mr. Spook catches it before it can shatter on the ground and deposits it neatly and safely on the front porch. So the crash doesn’t wake up the tenants.” Perhaps Mr. Merrifeld wasn’t quite ready to give up his duties as landlord.

In 1955, the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) announced its plans to overhaul Bunker Hill, and by 1968 the only residences of the bygone era that remained were the Castle and the Salt Box, located at 339 S. Bunker Hill. Both structures were set to be demolished on October 1st of that year, but were saved in the eleventh hour when the Recreation and Parks Commission voted to let the homes reside on city owned land at Homer and Ave 43 in Highland Park. Additionally, the Department of Public Works agreed to move the structures to their new home which would become known as Heritage Square. For the Cultural Heritage Commission, the decision came after a six year battle to save the structures. Once moved, the CHC would then face the task of raising enough money to restore the age-worn buildings.

The Castle and Salt Box were relocated to their new home in March 1969 using $33,000 appropriated by the City Council and $10,000 from the CRA. Almost immediately the structures were invaded by vandals. On October 9, 1969 both houses were set on fire. Within minutes, the lone survivors of Bunker Hill’s Victorian era were gone forever.

All photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection