When we last visited the Argyle, it was the a first rate Bunker Hill rooming house, artists’ salon, and night spot besieged by troubled management and unpredictable closings. This week, we turn to the Argyle’s tenants, and their various encounters with local law enforcement.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

On December 22, 1887, police were summoned to the Argyle at 2:30 in the morning, and greeted at the door by a hysterical landlady who claimed that the house was full of burglars, and "one of them is standing in a guest’s room with his throat cut!"

When we last visited the Argyle, it was the a first rate Bunker Hill rooming house, artists’ salon, and night spot besieged by troubled management and unpredictable closings. This week, we turn to the Argyle’s tenants, and their various encounters with local law enforcement.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

On December 22, 1887, police were summoned to the Argyle at 2:30 in the morning, and greeted at the door by a hysterical landlady who claimed that the house was full of burglars, and "one of them is standing in a guest’s room with his throat cut!"

A small army of police officer, reporters, and curious tenants rushed down the hall, storming into the room where the fiend had been sighted. Behind the door, however, they found a startled-looking, 100-pound man mopping up a bloody nose. And the kicker? He lived there.

Another early morning disturbance drew police on September 15, 1892. When they arrived at the scene, they found another crowd gathered around a door, listening to the anguished moans of a woman. After some heated debate, they decided to break down the door, and police were about to do just that when a man’s voice shouted, "Don’t kick that door open. She is alright."

As the Argyle residents exchanged scandalized whispers, a half-naked man flung the door open and attempted an escape, but succeeded only in running into the arms of police officers. Though both parties remained unnamed, the shirtless gentleman was a prominent local artist, and the woman a handsome widow "too far gone under the influence of ‘cold tea.’"

After a few incidents like this, the Argyle residents needed to step up their game, and how better than to take a page from Dickens? On June 29, 1901, Charles B. Howe was arrested and charged with enlisting two of the Argyle’s youngest residents to steal for him. Howe approached Raymond and Harry Neismonger, 11 and 9, respectively, with a proposition that they steal from local department stores, and he would purchase the fenced goods at bargain prices. Raymond was intrigued, and promptly took a job as a cash boy at the Broadway Department Store where he had easy access to all manner of tempting items. Not to be outdone, the younger boy took to lifting watches from Tufts-Lyon. Howe was caught red-handed with several watches, a bathing suit, and an assortment of leather goods in his possession.

Though our tale has run long, there’s room for one more Argyle crime, a sad, though routine tale of domestic violence immortalized in perhaps the purplest headline ever penned by a Times writer:

"CAUGHT BY STRATEGY: COWARDLY WIFE-BEATER WITH BLOOD IN HIS EYE AND MURDER IN HIS DRUNKEN HEART"

Charles Gregory stumbled into the Argyle drunk and proceeded to beat his wife. Police were summoned, and Gregory was locked up for disturbing the peace, though not for assaulting his wife.

Don’t know that the story lives up to the headline, but somehow, it fits the spirit of the Argyle Hotel perfectly.

Photographs from the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

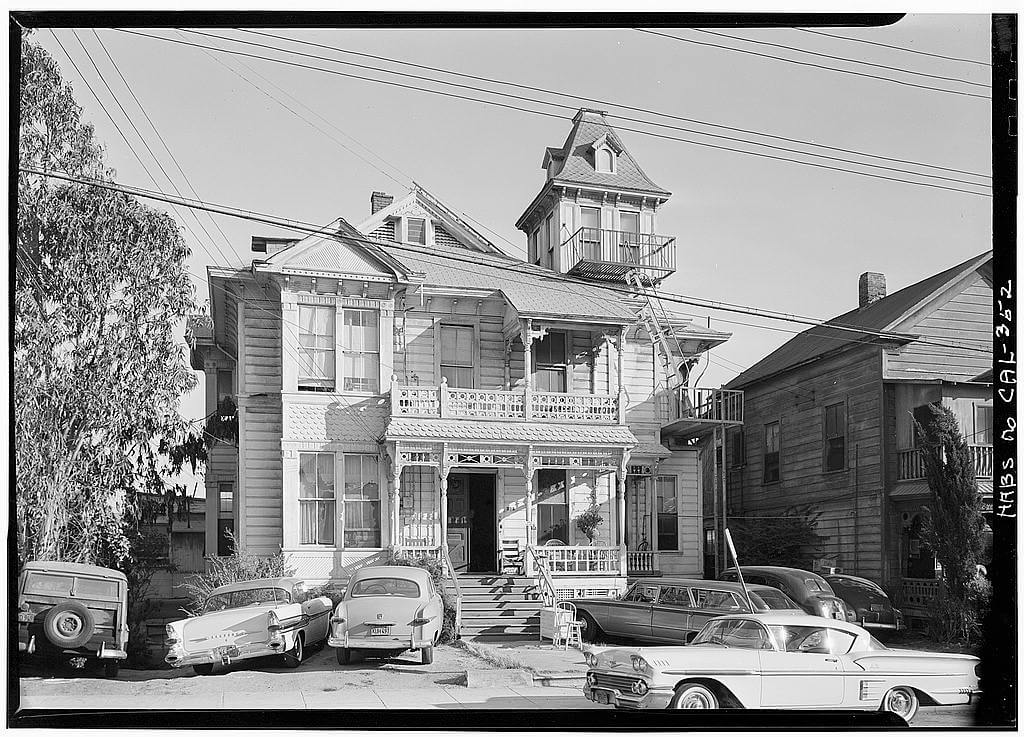

About which Bunker Hill photographer Arnold Hylen described as “a touch of old New Orleans along the sidewalk.” He‘s right not only about that wrought iron, which lends a decided Royal Street flourish. This is a shockingly New Orleans house in general. Granted, the steep cross gables are more Gothic Revival than archetypal Crescent City, but this style of roof treatment is seen frequently in New Orleans. The two-tiered porch with full-length windows are a Gulf Coast hallmark. Doubly remarkable is that this house, with its gingerbread at the upper gallery, choice of board over shingle, and single light in the center gable–evocative of the Creole cottage–was constructed contemporary to New Orleans‘s residential blanketing via the shotgun house (the four-bay arrangement of this home mirroring the double shotgun, though the door placement lends and air of the famous New Orleans centerhall villa). Granted, it‘s a little out of place here; those tall windows are intended to dispel mugginess, hardly a chief concern in the realm of Ask the Dust. Nevertheless, this wasn‘t a celebratory tribute to quaint olde New Orleans–it was built by and for Victorians.

About which Bunker Hill photographer Arnold Hylen described as “a touch of old New Orleans along the sidewalk.” He‘s right not only about that wrought iron, which lends a decided Royal Street flourish. This is a shockingly New Orleans house in general. Granted, the steep cross gables are more Gothic Revival than archetypal Crescent City, but this style of roof treatment is seen frequently in New Orleans. The two-tiered porch with full-length windows are a Gulf Coast hallmark. Doubly remarkable is that this house, with its gingerbread at the upper gallery, choice of board over shingle, and single light in the center gable–evocative of the Creole cottage–was constructed contemporary to New Orleans‘s residential blanketing via the shotgun house (the four-bay arrangement of this home mirroring the double shotgun, though the door placement lends and air of the famous New Orleans centerhall villa). Granted, it‘s a little out of place here; those tall windows are intended to dispel mugginess, hardly a chief concern in the realm of Ask the Dust. Nevertheless, this wasn‘t a celebratory tribute to quaint olde New Orleans–it was built by and for Victorians.

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

We humans may be nasally challenged with our measly 5 million scent receptors, but German Shepherds have 225 million ”“ and they know how to use them all.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.

At first, the hotel attracted the sort of person who perhaps wished for a bit more intrigue and drama than life at the Argyle provided. And being artistic types, they were perhaps prone to overactive imaginations.