Accursed rings! Hammer-mad Japanese! Arms-manufacturing Baronesses! Welcome to Zelda.

Somewhere in Los Angeles there‘s a burglar who‘s made off with more than he‘s bargained for”¦a maharajah‘s curse. Somebody stole into the Zelda Apartments in March of 1941 and there into the room of Mrs. F. S. Tintoff, making off with a 400 year-old ring that held two large stones, a ruby and an emerald, surrounded by small diamonds.

“It was given to me by my husband, a jeweler, who purchased it from a maharajah. The ring formerly adorned an East India princess, and was supposed to have been given a mysterious Oriental curse which would bring death to the person who stole it,” said Mrs. Tintoff. The burglar took other jewelry which with the ring had a value of $560 ($8,196 USD2007), and two other tenants in the apartment building reported similartly burgled jewelry losses to police, but nothing thereof with a curse upon‘t. The Tintoff ring thus joins other bloodstained jewels of the East, like the Dehli Purple Sapphire, the stolen-from-the-Eye-of-Sita Hope Diamond and the similarly snatched Black Orlov. And that deadly ring of Valentino.

Did our housebreaker lose this cursed thing to the ages as he writhed in some forlorn torment somewhere? Were his last days exactly like this? Or perhaps the curse was purely legalistic.

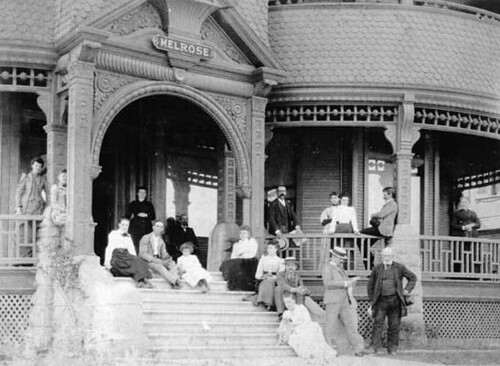

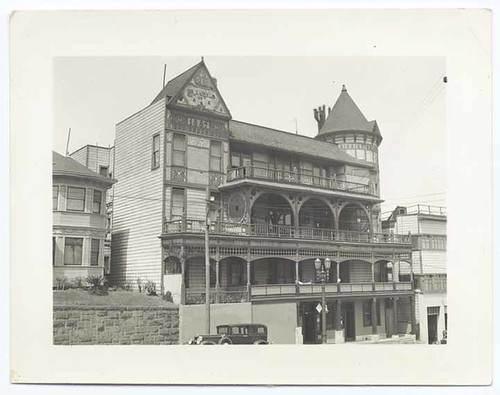

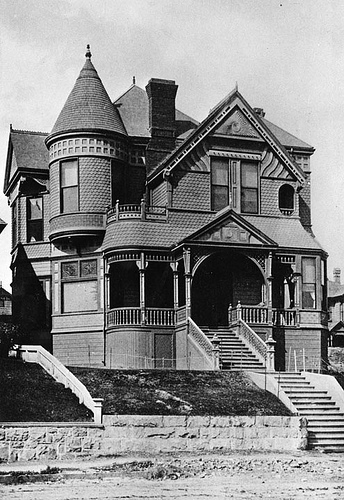

What, or who, is Zelda? Zelda La Chat (née Keil) was born in 1870, arriving in Los Angeles some time in the 90s. She builds the eponymous Zelda, a modest bargeboard affair at the southwest corner of Fourth and Grand, here, about 1904:

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres, across from the Huntington Hotel; eleven acres in Beverly Hills; and thirty-four acres in the Palisades near Santa Monica; and about $2.5million in mortgages, bonds and securities. Nine year-old Beatrice Denton, to whom Baroness von Zimmerman was benefactress, was supposed to be a beneficiary of the estate, but the Baroness never got around to those formalities. Foundling Beatrice became once again an orphan and was likely returned to the asylum from which she was plucked.

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres, across from the Huntington Hotel; eleven acres in Beverly Hills; and thirty-four acres in the Palisades near Santa Monica; and about $2.5million in mortgages, bonds and securities. Nine year-old Beatrice Denton, to whom Baroness von Zimmerman was benefactress, was supposed to be a beneficiary of the estate, but the Baroness never got around to those formalities. Foundling Beatrice became once again an orphan and was likely returned to the asylum from which she was plucked.

Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition.

Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition.

And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?)

And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?)

Postwar Zelda was full of fun too. Joseph M. Marcelino, 21, was just another ex-Marine who worked in a box factory. When he got nabbed on October 4, 1950, while burglarizing an apartment in the Gordon at 618 West 4th, he copped to having set fire to the Zelda, aflame at that very moment. He admitted as well to torching another hotel at 322 South Spring. He was freed without bail pending a psychiatric examination. But come April, when he broke into a factory at 1013 Santa Barbara Ave. and stole company checks, which he made payable to himself and cashed, the police came knocking.

Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

But the winds of change blew foul in 1954. Sure, people waved their arms and preached the evils of gingerbread ornament and its relationship to tuberculosis, but when you came right down to it, The Hill impeded traffic flow. A new project, known as the 4th Street Cut, began that Summer, involving a 687-foot viaduct shooting eastward from the Harbor Freeway, carrying four lanes of one-way traffic above Figureora and Flower, then biting into the hill and passing beneath bridges at Hope and Grand before dipping down into the business district. Through the early 1950s there was much controversy over this plan–proponents of a tunnel argued that a cut would “hopelessly bisect” Bunker Hill. What they didn‘t realize was that soon enough, there‘d be no Bunker Hill to bisect.

Fourth Street, in becoming a cut, and Grand, in becoming a bridge, meant one thing: the surrounding buildings would have to go. And so they did. The Zelda was razed in August of 1954:

Seen being demo‘d next to the Zelda is the Gordon at 618 West 4th (you remember, the place Marcelino was nabbed in in ‘50); the Gordon, the Bronx at 624 and the La Belle at 630 West 4th were all torn down to make way for the Cut–a trio built by the sons of Dr. John C. Zahn.

All this brought a twinge of regret to Percy Howell, the veteran city appraiser who spent two years tramping the Hill, working out fair payments for displaced property owners. Howell remembered his young bachelor days on Bunker Hill back in 1909, when he moved into the Zelda, “batching it” with three other gay blades. “I never dreamed then,” said Howell, “that I would live to see the day when I condemned the Zelda for the city.”

The 4th Street Cut opened May 1, 1956.

A new an improved 4th St., looking east ca. 1964, foundation excavation for the Union Bank in the foreground:

Another shot of the viaduct (I know, why-a no chicken?) ca. 1973, during erection of Security Pacific Plaza.

For twenty-five years after Zelda‘s demolition, nothing could stem the march of progress:

It has filled in now, to be fair.

And so goes Zelda La Chat, her Zelda, and 4th Street, though all we have to show for the former glory of 401 South Grand is the pointy backside of 400 South Hope.

Photographs courtesy USC Digital Archive

After our initial report on

After our initial report on

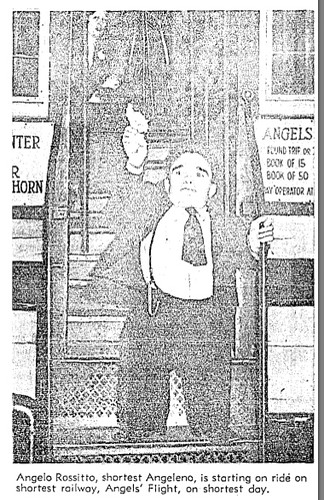

March 11, 1961. Alfred Carrillo, 33, was a Dome resident in good standing who had the bad luck to be sitting in a bar at 301 South Hill Street one early Friday morning. Victor F. Jimenez, 26, unemployed truck driver, shot Alfred and then drove off, later to be arrested at his home. (The bar at 301 South Hill, by the way, was the bar at the base of Angels Flight–seen here with Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1956 outing

March 11, 1961. Alfred Carrillo, 33, was a Dome resident in good standing who had the bad luck to be sitting in a bar at 301 South Hill Street one early Friday morning. Victor F. Jimenez, 26, unemployed truck driver, shot Alfred and then drove off, later to be arrested at his home. (The bar at 301 South Hill, by the way, was the bar at the base of Angels Flight–seen here with Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1956 outing

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.  On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock. But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

February 27, 1911. It‘s 9:30am, and

February 27, 1911. It‘s 9:30am, and