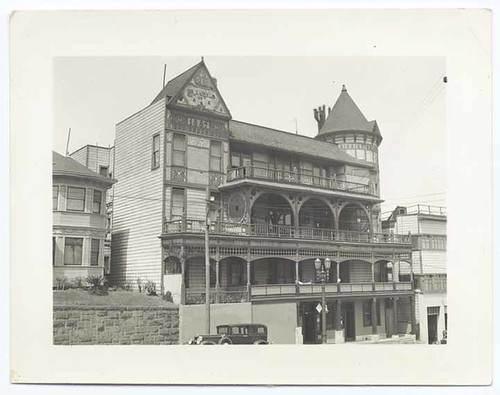

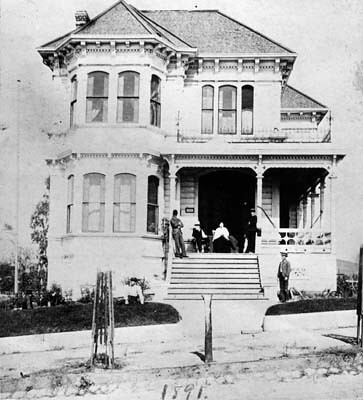

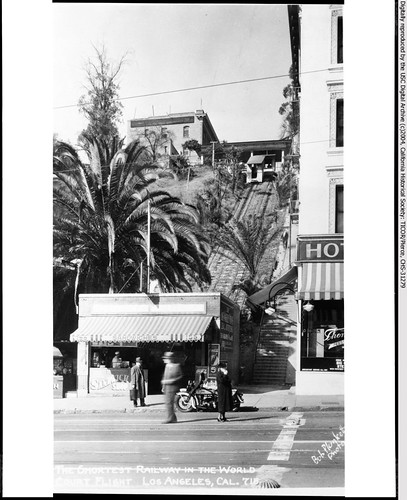

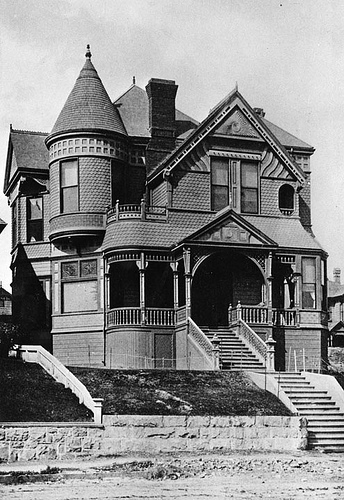

Of the two cable car lines that ran through Bunker Hill in the late 1880s, the Second Street Railway was the first to be financed and functioning, but the Temple Street line would prove to be more durable and longer lasting. While the cable cars of Los Angeles are now just a very small footnote in the city’s history, the Temple Street Railway was for years, a reliable mainstay for Bunker Hill residents in the waning days of the Victorian era.

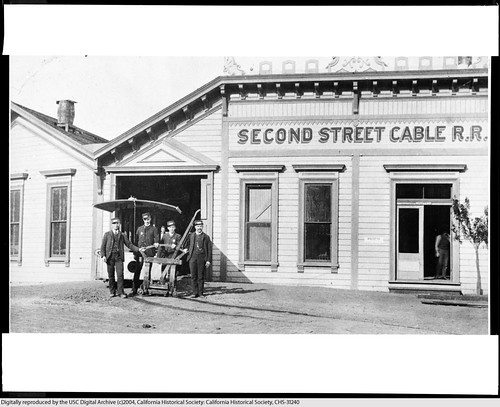

Cable cars did not come to Los Angeles until 1885, even though a local paper suggested in 1882 that a line running up Temple and over to the Normal School (where the Central Library now stands) would be a good idea. The Temple Street line was conceived of around the same time as its Second Street counterpart, but while the latter immediately had investors reaching into deep pockets, the raising of funds for the Temple cable cars was slower going. A month after the Second Street line was completed, the Temple Street Cable Car Railway Company was finally able to incorporate with a Board of Directors that included Walter S Maxwell, Victor Beaudry, Ralph Rogers, Thomas Stovell, Julius Lyons, E.A. Wall, O. Morgan, Prudent Beaudry and John Milner.

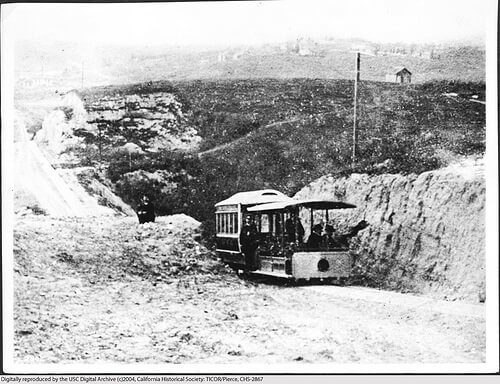

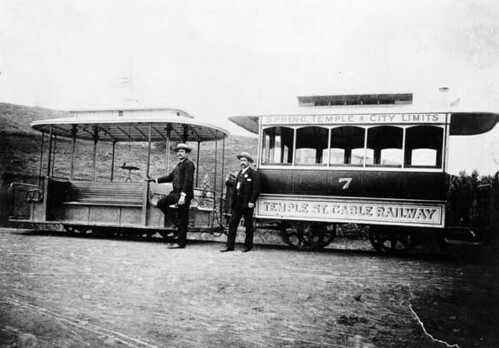

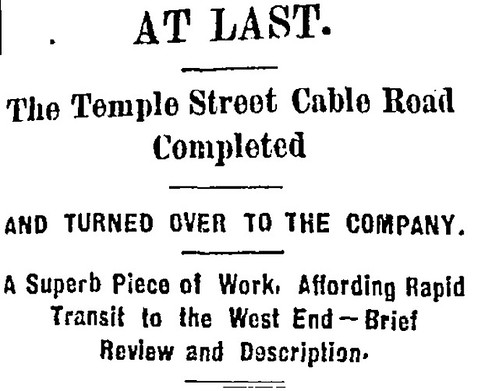

Work on the line began in December of 1885 and was estimated to be completed by the following May. Unlike the Second Street line which was constructed rapidly to capitalize on the real estate boom of the 1880s, the Temple line was built with considerably more care. Completion of the railway was delayed, mainly due to wait times on parts ordered from around the country, and the Temple Street cable car made its eagerly awaited inaugural trip through Bunker Hill on July 14, 1886.

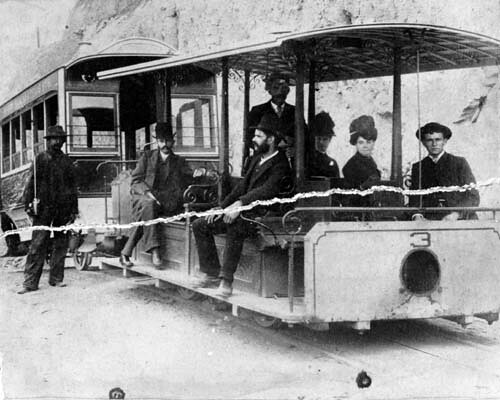

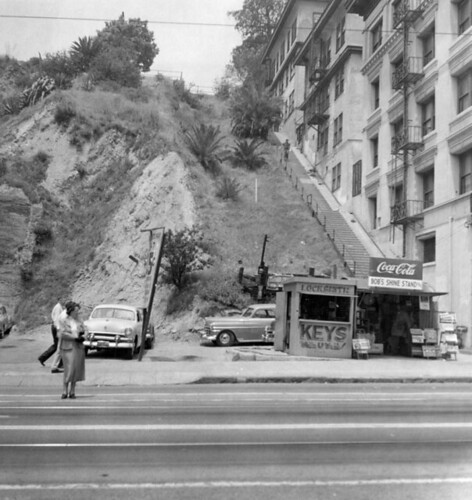

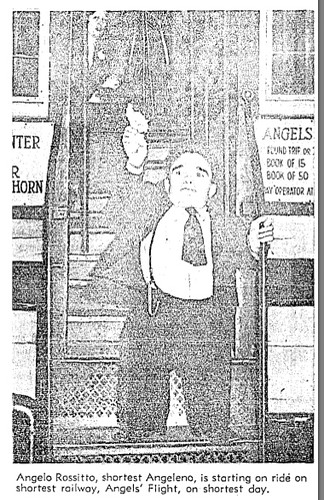

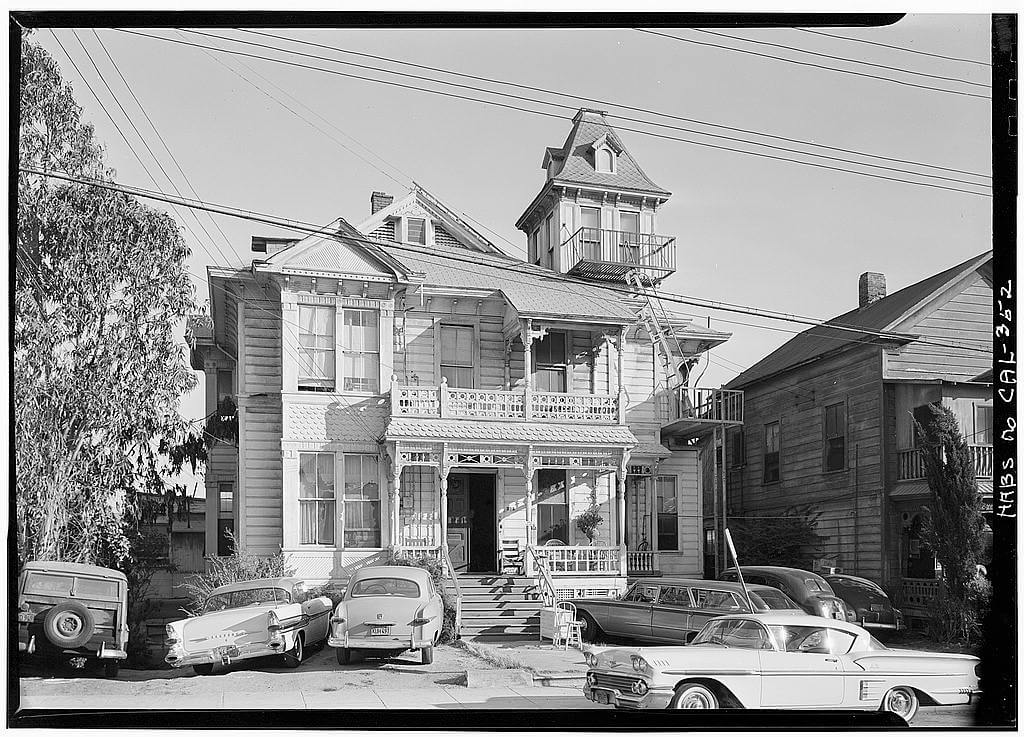

The Temple line cost $90,000 to construct (around 2 million in today’s dollars) and would require roughly 600 passengers a day, each way, to make a profit. The cars, built by the John Stephenson Co of New York, held fourteen passengers and according to the Los Angeles Times, “are models of elegance and easy motion.” The line initially ran 1.6 miles up Temple from Spring to Belmont, and would eventually be extended to Hoover in an area then known as Dayton Heights. Unlike the failed attempt of the Second Street line to connect with the Cahuenga Valley Railroad, the Temple Railway was successfully connected with the steam cars which allowed passengers to transfer from one line to another and travel out to Hollywood.

Tragedy struck the Temple Street Cable Railway on the morning of January 16, 1892 when James Brown, a 51 year old employee of the railway company for six years, was killed in a freak accident. Every day, Brown would oil the wheels from the end of the line up to the powerhouse on Edgeware near Echo Park. On the fateful morning, a piece of Brown’s clothing was caught between a cable and the wheel. The speed of the wheel pulled his arm off and as the Times reported, “he was terribly mangled around the head and face, and several bones were crushed, so that death must have almost been instantaneous.” Almost a year later, Brown’s widow would be awarded $20,000 from the Temple Street Railway Company.

Great flooding in 1889 would obliterate the Second Street line, but the better built Temple railway would persevere with little interruption to service and would carry 1.5 million passengers by year’s end. This would prove to be the pinnacle for the line, which never turned much of a profit and was near bankruptcy by 1897. The cars managed to chug along for another few years, but by 1902 they were breaking down frequently and many residents opted to walk along the rails instead of waiting to catch a ride on these relics of a bygone era. The railway was purchased by railroad magnate Henry Huntington in late 1901 who would eventually make the line an electric one. On November 18, 1902, the cable cars on Temple Street officially stopped running.

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection