It’s not an Edwardian octoplex full of grime and grifters. It‘s not even on Bunker Hill. But we‘re going to tell the tale of the Architects‘ Building, and if not to you, faithful OBHer, then to whom?

All and sundry weep for the Richfield. It‘s not altogether true that everyone turned a blind eye during its”68-9 demo. Even the Government knew enough to come on out with its Instamatic and take lots of snaps.

The November 1968 Times article “Black and Gold Landmark: End Arrives for LA‘s Richfield Building” discusses those architecture students who believed the structure a remarkable example of “Jazz Moderne” worthy of preservation.

And the only mention of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth (which by 1968 had been renamed the Douglas Oil building) and which shared the block with the Richfield was as such:

”¦and that was the end of that. According to Cleveland Wrecking‘s general manager, the million-dollar site clearance project, of the block bordered by Fifth, Flower, Sixth, and Figueroa, was the largest ever undertaken in the West.

What is this Architects‘ Building of which we speak? Who architected this interbellum edifice?

Downtown is very nearly defined by Parkinson, and you can‘t mention LA without Morgan, Walls & Clements (Stiles sitting in the softest spot of this writer‘s heart), and if I mention Walker and Eisen, you‘ll say Yaaay! and I‘ll agree, and we‘ll high-five, and then get cut off and kicked out of wherever we are. It sure is swell to take those Conservancy tours and see all these places, but when the Conservancy cats go back to their digs, they return to a Dodd and Richards.

And you say, who?

William J. Dodd, student of Jenney and Beman is one of the great Midwestern architects. He came to California and is credited–though scholars still dispute to what extent–with a portion of Julia Morgan‘s 1914-15 Examiner Building. This he did with his partner at the time J. Martyn Haenke. In 1916 he partners with engineer William Richards. They produced so many an important Los Angeles structure that I will at some point in the near future add their full history as a comment appendage to this text, to keep from having too many appetizers before our twelve-story entrée.

We’re talking about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa, not to be confused with our friend on the kitty-corner to the northwest, the Monarch Hotel.

The first rumblings about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa come in February 1926, when mention is made of preliminary plans and lease negotionations for a million-dollar skyscraper to house LA‘s building trade. Sponsoring the project are Morgan, Walls and Clements, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, Webber, Staunton and Spaulgin, Carlton Monroe Winslow, Elmer Gray and McNeal Swasey.

The big announcement is made in February 1927 about the $650,000 height-limit to be built on the southeast corner of the Fifth and Figueroa. To be known as the Architect‘s Building, after New York and Chicago, it would be the third of its nature in America: a whole structure exclusively devoted to the various branches of the construction industries. It is to be of a “modified Italian” architectural treatment according to the associated architects drawing up the specifications: Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carleton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson.

Twelve stories high, with a site of 60 by 156 feet, it is to be of steel reinforced concrete, 143 offices, its exterior finished in plaster with cast-stone trimmings. Its seven upper floors of the building are to be leased to prominent architects, its first floor and mezzanine to be occupied by the Metropolitan Exhibit of Building Materials–a massive exhibit of every branch of the building industry, renamed the Architects‘ Building Materials Exhibit.

By November of 1927, the building was nearing completion. Preston S. Wright, president of Wright-Aiken, owners of the AB, ran down some of the tenants: Rapid Blueprint Company; D. C. Writhg, insurance; E. E. Holmes, insurance; William Simpson Construction Company, builders; Brian D. Seaver, attorney; and architects D & R, Coate, Johnson, Winslow, and William Lee Wollett.

816 opens in January, 1928. It came in at $662,000.

The depression would not be good to the Architects‘. It was foreclosed on its $360,000 outstanding bonds in February 1933. It was put under federal receivership and forced into a court-ordered sale, which didn‘t occur until May of 1938, when an F. V. Fallgren and associate could pony up the 300k to a trustee representing the bondholder‘s committee.

The Architects‘ Building survives just fine through the 40s and 50s.

One bit of drama: Evans Erskine, 34, a jobless Air Corps vet, figured that 1955 would be Year Last. He climbed to the ninth-floor fire escape of the Architects‘ Building and hoisted himself over the railing. Richard McGowan, a controller for Dames & Moore Civil Engineers, ran down the hall and and grabbed the hands of the nattily dressed, ledge-teetering Erskine poised 100 feet above Fifth Street. Here, McGowan reenacts his daring hand-grabbing:

In 1959 it is purchased by Douglas Oil, a southern California independent who run three refineries and 300-some gas stations in the Southland. It remains the Douglas Oil building despite Douglas‘ purchase by Continental Oil (AKA Conoco) in 1961.

It‘s the 1960s when the folk in 816, heck, the building itself, could hear the dirge of doom wafting on the wind. Listen, it‘s coming from over by the Richfield building.

Richfield, another oil company, who owned that big ol‘ black and gold tower to the south, had merged with east coasters Atlantic Refining in 1966. Richfield had already begun buying up the block for piecemeal parking, and as Atlantic-Richfield Co. they purchased the whole kit. And kaboodle. That called for the end of the Architects‘, as ARCO intended to build not one but two Miesian towers (though their New York twin-tower counterparts broke ground four years earlier, there appears to be an aesthetic epoch between AC Martin’s work and Yamasaki’s tube-frame twins of lower Manhattan, whose postmodern sensibility stems from a neo-Gothic use of aluminum).

1967, and all‘s well:

1969, during the demolition. The Architects‘ Building, now one-fifth off! The Richfield, now with two-thirds less Richfield!

1970, towers going in.

Left to right, the Tishman Building (Victor Gruen, 1960, though you know it like this), Glore Forgan Staats, the Gates Hotel (now a fine Brooks Bros), St. Paul‘s Cathedral (razed), the Hilton (note how it changed from the Statler to the Hilton between 67 and 69), the Jonathan Club , the Carlton Hotel (razed), Caldwell Banker.

Below, today. Note the wee bit of the Jonathan peeking out.

The ARCO Towers still stand in all their glory. For now.

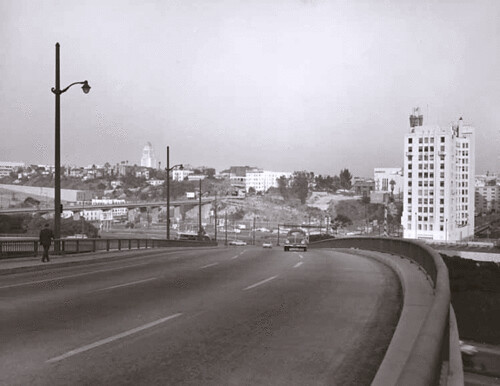

Another shot of the demolition. The Sunkist, Engstrum and Edison line Fifth. The Telephone Tower on Grand. In the distance, left, Bunker Hill Towers going up.

A mid-60s aerial. Central Library bottom right. The Sunkist at Fifth and Hope. Halfway up Hope behind the Sunkist, the tiny Sons of the Revolution and the Santa Barbara. The big apartment building at the southwest corner of Fourth and Hope was the Barbara Worth.

Of course we’re not getting away without the requisite model and Sanborn additions:

Note how Fourth Street ends at Flower. Compare to the 60s aerials which indicate the magnitude of the 1954 Fourth Street Cut.

Just to clear up one bit of confusion. Despite early mention that this building was to be of the combined effort of Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carlton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson”¦it‘s a Dodd and Richards. Even Adrian Wilson, who in April 1967 wisecracked “I hope our new location won‘t be so temporary” in an article about his having to move out of the AB after thirty-nine years, remarks that Dodd and Richards designed the building–and he should know, the plans for 816 are inscribed with his own initials, as he was their draftsman before he hung out his own shingle when the building opened in 1928.

Clockwise from the south: Sixth, Figueroa, Fifth, Flower:

That then is the tale of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth. Remember the diaspora the next time you‘re in the neighborhood.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library photo archive, University of Southern California, and Arnold Hylen and William Reagh Collections, California History Section, California State Library

Did we not promise, above, that if you were good, and read all your Architects’ Building, you’d be rewarded with a first-time-ever accounting of Dodd and Richards?

Okay, so you didn’t read that one part, but we still want poor neglected Dodd and Richards to have their day in the sun, so please look at the pretty pictures below. (Of which there are many, so if you have dialup, go make a sandwich or something.)

William Richards is born in Darlington, England in 1871. Queens College Cambridge ’91. Emigrates to the ‘States in 1912.

William J. Dodd’s pre-Los Angeles era is pretty well covered in his Wikipedia page.

On his arrival in LA, Dodd starts with J. Martyn Haenke (who’ d just come off the gates at Fremont Place).

In May 1913 Dodd and Haenke are given the greenlight for a fourteen-story steel frame office building at the corner of Eighth and Spring. For reasons lost to the ether, this does not occur: while there are now office buildings on three of the Four Corners, they are all of early 1920s vintage, and none are Dodd and/or Haenke. The fourth corner, where once stood the 1887 Armory Building, steadfastly remained the Armory (becoming a dance hall in its final days, truth be told) until its demolition for a parking lot in October 1938.

In 1913 Dodd and Haenke, with one Julia Morgan, design a Beaux Arts-house for Dr. Peter Janss at 455 S. Lorraine. Janss is that developer of Holmby Hills, Westwood and many a Los Angeles subdivision. In 1950 455 becomes the home of Norman and Dorothy Buffum Chandler. As owner of the Times, Mr. Chandler dubs the house "Los Tiempos" ("The Times") though it’s also known as El Western White House—Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon are repeated guests. Sold to Timothy Corrigan after Dorothy Chandler’s death in 1996, it becomes Historic-Cultural Monument #863 in 1997.

In January 1914 Jay Morris Danziger, son-in-law of the late Charles Adelbert Canfield, sought to build a palace-on-a-hilltop just outside of Beverly Hills (the northwestern slice of the Wolfskill Ranch, largest orange groves in the world), and turned to William J. Dodd. The resulting house was a 250’ Italianate villa of thirty-five rooms with a dooryard of 2,000 acres, built to conform to the natural shape of the hill on which it was perched.

The resulting house was a 250’ Italianate villa of thirty-five rooms with a dooryard of 2,000 acres, built to conform to the natural shape of the hill on which it was perched.

In 1922 Alphonzo Bell, of Bell Petroleum, purchased this to enlarge his adjoining property, thereby making the sum total 4,500 acres; his resulting subdivision became known as Bel-Air.

In a spiritualist séance, Haas told Mrs. Lizzie Schaadt that her husband—dead thirty-five years—advised her to invest $8,000. A Mrs. Flynn was also taken in by the spook show and brought suit against Haas’ swindle. But hey, it’s not Haas’ fault that poltergeists liked Dodd’s drawings.

Of course 1914 is also known as the year of Dodd and Haenke’s contribution to the Examiner.

In 1916 Boyle Heights is fortunate to get a Carnegie-granted Dodd and Richards library at 2200 East First St. Here is a 1975 photo of the locals cheering for the demolition of all that nasty ol’ Eurocentric classicism.

Here is a 1975 photo of the locals cheering for the demolition of all that nasty ol’ Eurocentric classicism.

Dodd and Richards are noted in December 1916 for their forthcoming and expected commercial/residential project in Hollywood (how New Urbanist!) with six stores at sidewalk, nineteen apartments second story, at Santa Monica and Gower. If it ever was, it’s gone from the neighborhood now. This writer works on the romantic assumption that it was built, but without proof (trust me, I’ve tried), he and we must wear on our collective sleeve that it is just an assumption.

If it ever was, it’s gone from the neighborhood now. This writer works on the romantic assumption that it was built, but without proof (trust me, I’ve tried), he and we must wear on our collective sleeve that it is just an assumption.

Now then. It’s 1916, and Dodd and Richards have partnered. They begin to bud. They have the will to flower. It is time.

In 1917, Los Angeles was proud to have a new motion-picture theater: the Kinema. At 642 South Grand, it was a true picture-house, stage only seven feet deep, seating 1,856. Its severe Franco-Renaissance façade was faced in terra cotta. And according to some pretty persuasive evidence here the Jazz Singer did not, as is oft-reported, have its LA opening at the Tower, but at the Kinema.

Its severe Franco-Renaissance façade was faced in terra cotta. And according to some pretty persuasive evidence here the Jazz Singer did not, as is oft-reported, have its LA opening at the Tower, but at the Kinema.

The Kinema became the Criterion in 1921. It was demolished in 1941 for an office building, which was in turn demolished and is now part One Wilshire, now part parking lot adjacent One Wilshire.

The Kinema became the Criterion in 1921. It was demolished in 1941 for an office building, which was in turn demolished and is now part One Wilshire, now part parking lot adjacent One Wilshire.

I confess to being confused by this building. Though a Barnett Haynes & Barnett, 1911, City Records show it to be 1917, probably because Dodd & Richards worked an addition to it in that year. But what was their addition? According to renderings, they were to turn the building into an L-shape with a tower down Grand. That didn’t happen. The smaller building to the south is theirs, and 1917, see it during its construction below. This writer thinks the Brockman has more Dodd and Richards than history will allow at the moment; we’ll update as more is revealed.

1917 is a big year on Seventh; it’s a big year for Dodd and Richards on Seventh. It’s practically the Museum of Dodd and Richards do 1917 on Seventh Street Museum, Museum.

Why is Seventh Street so important? Let’s tie it in to Bunker Hill a little bit, 1917-style:

district and the rapidly–growing west and northwest residence section,

and it has been inevitable that unless serviceable outlets through the

hill were provided, business would swing around this great obstruction

as soon as it had advanced far enough south. Seventh street being the

first through cross street below the hill, it has always the entry way

into the business district for all the traffic that has been force to

go around Bunker Hill as well as for much of the traffic of southwest

Los Angeles. Shopping was bound to follow this way of least resistance,

especially in view of the fact that this path lay directly toward the

best residence districts in the city.

You may have heard that there’s a Greene and Greene department store downtown; well, it’s a Dodd and Richards. They did the 1917 Coulter Dry Goods Store, and the Greenes did some interior alteration work. Dodd and Richards’ Coulter blueprints are at the Avery; see them here.

Across from the Coulter Dry Goods is the Ville de Paris Department Store. As much as I want to ascribe the VDP to D&R, the only information I have linking them to its erection at the time of this writing is this page. For the time being we’re going to call it a D&R but more digging is necessary.

This, though, is for certain. Pigeons like to fly in and out of the burnt-out upper stories.

1917 also sees the arrival of the Huntsberger-Mennell Building, 412 West Seventh, whose foundation is equipped to take six stories, but only two are ever built. The original tenants are the Wetherby-Keyser Shoe Company, Bartlett Music Company, and the Yamato.

The original tenants are the Wetherby-Keyser Shoe Company, Bartlett Music Company, and the Yamato.

1917 saw the demolition of a collection of old frame buildings at the southeast corner of Eigth and Santee; Dodd and Richards designed a nifty Mission-style garage with a glazed enamel-brick front for the Ponet Estate Company. The building became the western headquarters for the Otis Elevator Co., and was also leased to Arthur Maas, a chemist who produced, among other things, SoCal-styled chemicals like developers for the motion picture industry, and orchard sprays for the fruit trade. Maas was also the chemical expert for the Coroner’s office; it’s Maas you see digging around in the Denton “death basement” of 675 S. Catalina looking for clews. The D & R garage is parking-lotted in 1960.

The building became the western headquarters for the Otis Elevator Co., and was also leased to Arthur Maas, a chemist who produced, among other things, SoCal-styled chemicals like developers for the motion picture industry, and orchard sprays for the fruit trade. Maas was also the chemical expert for the Coroner’s office; it’s Maas you see digging around in the Denton “death basement” of 675 S. Catalina looking for clews. The D & R garage is parking-lotted in 1960.

Oh those Uplifters! The congregation of merry-makin’ musclemen off-shot from the LAAA and headed down to the Coronado. Transportation for the pilgrimage is arranged by Uplilfter John Byrne of the Santa Fe, who also captained the Track Walkers in a game of railroad ball against the Section Hands, captained by Uplifter William J. Dodd. The high jinks play along the road will be “The Orpheus Road Show,” by L. Frank Baum and Louis Gottschalk (fresh off their successes with the Oz pictures).

Dodd and Richards were in the garage business again in 1918, designing a brick garage for the Ponet estate, 100×150’, on Hope between Twelth and Pico. The only garage on Hope between those two streets from 1918, and with those particular measurements, is at 1230-1240 South Hope: Not much to look at now, sadly, though if you’re in the neighborhood take a gander at the tile on the California School Book Depository (as evidenced by the ghost signs on its sides) across the street.

Not much to look at now, sadly, though if you’re in the neighborhood take a gander at the tile on the California School Book Depository (as evidenced by the ghost signs on its sides) across the street.

According to the October 1919 issue of The Architect and Engineer, Dodd and Richards were the architects of the Beverly Hills Speedway. D&R’s speedway was designed for managers A. M Young and Jack Prince of the Beverly Hills Speedway Syndicate for the Los Angeles Speedway Association. The 200+ acre site with its one and one-quarter mile track of frame construction, with all the attendant grandstands, garages, utility buildings, etc. is thrown up shockingly quick (Wikipedia states they used 2×4 floorboards for the classic oval board track; contemporary accounts state they were 2×3) and disappears almost as quickly. Open in February 1920, it is closed in February 1924, and Beverly Hills High and the Beverly Wilshire Hotel show up in 1927 and 28, respectively.

The 200+ acre site with its one and one-quarter mile track of frame construction, with all the attendant grandstands, garages, utility buildings, etc. is thrown up shockingly quick (Wikipedia states they used 2×4 floorboards for the classic oval board track; contemporary accounts state they were 2×3) and disappears almost as quickly. Open in February 1920, it is closed in February 1924, and Beverly Hills High and the Beverly Wilshire Hotel show up in 1927 and 28, respectively.

Dodd is appointed to the State Board of Architecture, October 1919.

1919 sees the erection of Dodd and Richards’ four-story reinforced concrete building for the Ponet Company at the southeast corner of Twelth and Hope:

Built to be leased to REO Motor Cars, there’s still a ghost sign on its backside:

The lease changes hands to Hudson & Terraplane in 1939, where they stay until 1948. It becomes the General Fire-Proof Building, dealers of fine metal furniture. In 1962 it become the offices, showrooms, warehouse and cutting rooms of Campus Casuals, one of the market’s largest active sportswear firms. It’s still a clothing concern, although now it’s just known as “Basement the $10 Store.”

A late-30s shot of its ground floor:

And today:

In 1920 J. S. “Father of Torrance” Torrance got it into his head to build a market at 843-853 South Spring. He called Dodd and Richards, who designed a concrete, two-story, 150×165 building for Torrance, who leased the property for fifty years from pioneer resident D. Botiller. It is demolished for a parking lot in 1983.

In August of 1920 there was talk of a Dodd & Richards-designed twelve-story, 1500 room, $3,000,000 hotel on Grand near Sixth, though all available research indicates it was never built. It would have, after all, been very near the city’s premier hostelry, the Sixth and Grand Morgan, Walls and Clements’ 1917 Savoy Hotel.

1921 starts off with the announcement for a Dodd and Richards theater and apartment complex in Long Beach on Ocean between Locust and Collins. It is to be a monster. Eight stories of brick and cast stone with an Does it open? Either it was to be sited on the land on which the Breakers hotel was built. Or across the street. If that were the case, the 1,200 seat Capitol would likely not have been built the other side of the Breakers at Locust and Seaside. Apparently the owners of the site, the developers, whomever, decided to go…another way. (Auditioning actors, as architects, often hear "we’ve decided to go…another way.") A smaller Walker and Eisen/Clifford Balch theater is eventually built on the site in 1929.

Does it open? Either it was to be sited on the land on which the Breakers hotel was built. Or across the street. If that were the case, the 1,200 seat Capitol would likely not have been built the other side of the Breakers at Locust and Seaside. Apparently the owners of the site, the developers, whomever, decided to go…another way. (Auditioning actors, as architects, often hear "we’ve decided to go…another way.") A smaller Walker and Eisen/Clifford Balch theater is eventually built on the site in 1929.

Egyptian-styled auditorium to seat 2,600. The stage, 50×30’ to be built to

handle any type of performance, with an orchestra pit for seventy. A

60×150’ plunge pool below. Two lobbies, plus the usual nursery,

smoking and lounging rooms separated by gender, etc.

The big news of mid-1921 is the completion of the Pacific Mutual. Of 1921’s Pacific Mutual, what need be said? Go take a tour and see what four million 1921 dollars buys: acres of imported Tavernello marble, bronze, and hardwoods, and on the exterior, the largest Western order ever placed for terra cotta.

Of 1921’s Pacific Mutual, what need be said? Go take a tour and see what four million 1921 dollars buys: acres of imported Tavernello marble, bronze, and hardwoods, and on the exterior, the largest Western order ever placed for terra cotta.

In 1921 Everrett W. Perry, City Librarian, stressed the need for a brave, new, modern library: movable partition walls, a library school, a children’s room. Dodd and Richards sketch something for the new LA Central.

In 1921 Dodd and Richards design a two-story, twelve room residence for Laughlin Park pioneer Kenneth Preuss, to cost $30,000. The address was 7 Laughlin Park Drive; the house had to be nice, as Preuss—VP of Halbriter’s men’s haberdashery, and a dabbler in insurance, automobile sales, and real estate speculation—was to be Dodd’s neighbor; Dodd himself lived at 5 Laughlin Park (in a twelve-room frame house he built in 1914). By the time Dodd died 1930 he’d moved to the 1928-built 1975 De Mille Drive, a few doors down from Cecil DeMille, who lived at 2000. (Carlton M. Winslow lived at 1943 Laughlin Park, btw.)

In 1922 Dodd builds a house at 5226 West Linwood in Laughlin Park (which becomes the future home of Deanna Durbin).

Anyone remotely familiar with downtown knows the Hotel Clark. A 555-room monolith of steel and stone that took eighteen months to build (easy to overlook Harrion Albright’s building because one is always gazing at the giant art deco neon sign), Eli P. Clark’s hotelus gigantus opens January 1914. But was it big enough? Dodd and Richards were sent for when it was time to expand to the south. The three-tower structure, seventy feet along Hill and 165 feet deep, will contain 250 rooms, bringing the total number above 800. This dream goes unrealized.

But was it big enough? Dodd and Richards were sent for when it was time to expand to the south. The three-tower structure, seventy feet along Hill and 165 feet deep, will contain 250 rooms, bringing the total number above 800. This dream goes unrealized.

What is built in 1922 is one of LA’s most famous buildings, at least among the drinking class. The Brock & Company building at 515 W. Seventh was justifiably famous beforehard for its exterior finished with polychrome terracotta (a treatment you’ll recall from the Huntsberger-Mennell) and bronze fittings. The first two floors are sales rooms, offices and manufacturing above. The floors are of Tennesse marbke, the cases, Honduran mahogany. The interior has arched and groined ceilings decorated with plaster relief moldings, and the walls are lined with murals by Willis and Macauley of the Wilmat Studios, set in art nouveau panels, depicting the architecture and foliage of Versailles. The display cases are filled, in 1975, with china and bric-a-brac when Clifton’s Silver Spoon cafeteria moves in. It becomes the Seven Grand in the spring of 2007.

The first two floors are sales rooms, offices and manufacturing above. The floors are of Tennesse marbke, the cases, Honduran mahogany. The interior has arched and groined ceilings decorated with plaster relief moldings, and the walls are lined with murals by Willis and Macauley of the Wilmat Studios, set in art nouveau panels, depicting the architecture and foliage of Versailles. The display cases are filled, in 1975, with china and bric-a-brac when Clifton’s Silver Spoon cafeteria moves in. It becomes the Seven Grand in the spring of 2007.

Announced in March of 1921, though girders and uprights didn’t go in until January 1923, Dodd and Richards are to enlarge the Noonan and Richards 1914 Robinson’s building at Seventh and Grand, by adding sixty feet on Grand and Hope all the way across Seventh, a depth of 332’. Note its 1914 width: In the rendering it’s noticeably wider (i.e., deeper down Grand)

In the rendering it’s noticeably wider (i.e., deeper down Grand)  but the façade gets a total modernization by Edward L. Mayberry in 1934.

but the façade gets a total modernization by Edward L. Mayberry in 1934.

I didn’t mention Uplifter Dodd’s Uplifter March of 1917 idly. Again, the Uplifters: prominent Angelenos, an offshoot of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, who romped around Rustic Canyon drinking and dancing and staging lavish productions; Dodd was a founding member. When in 1923 their clubhouse burned to the ground, they called upon Brother Dodd. He responded in red tile vernacular: the best part about Spanish Colonial Revival is that it doesn’t burn down terribly earsily. All that adobe, you know. D&R’s building, a 118 x 284’ one-story affair, with a loggia and recessed gardens adorned with fountains, was constructed at the edge of a declivity overlooking a valley. Lawns, tennis courts and a pool were below. Inside, the club was equipped with a 25×50’ stage in a 75’ long auditorium, fitted for motion picture exhibition as well. The kitchen was so large and modern that it could service the main dining room, club room, private dining rooms and tea garden all at the same time. For the next thirty years the Uplifters (or Cuplifters, as they kept themselves wet through the dry times, bless ‘em) it was crazy musicals and nutty sports and summer outings. It eventually became the Rustic Canyon Park Recreation Center Co-Op and Nursery Center, and was declared Historic-Cultural Monument #663 in 1999.

Lawns, tennis courts and a pool were below. Inside, the club was equipped with a 25×50’ stage in a 75’ long auditorium, fitted for motion picture exhibition as well. The kitchen was so large and modern that it could service the main dining room, club room, private dining rooms and tea garden all at the same time. For the next thirty years the Uplifters (or Cuplifters, as they kept themselves wet through the dry times, bless ‘em) it was crazy musicals and nutty sports and summer outings. It eventually became the Rustic Canyon Park Recreation Center Co-Op and Nursery Center, and was declared Historic-Cultural Monument #663 in 1999.

Also in 1923, it is announced that Dodd and Richards have drawn up plans for the Arcady, Wilshire and Rampart:

For those of you who really know your Wilshire, you’re either saying that ain’t the Arcady, or the Arcady’s a Walker and Eisen, or both. And you’d be right. The Arcady folk decided to go…another way. The Walker and Eisen Arcady doesn’t go up for another four years.

They do, however, get the contract to design the Physician’s Building for this site, the southeast corner of Sixth and Lucas. A consortium of thirty-three doctors from the nearby Good Samaritan are behind the $350,000 project. Each suite will have waiting, consultation, examination, and dressing rooms, fitted with compressed air, gas, and industrial electricity.

Each suite will have waiting, consultation, examination, and dressing rooms, fitted with compressed air, gas, and industrial electricity.  Here is a shot of RFK’s hearse, the Physician’s Building in the background.

Here is a shot of RFK’s hearse, the Physician’s Building in the background.

In April 1923 they announce a Class-A office building for the southwest corner of Sixth and St. Paul. To be 80×165, to cost $500,000. That corner—once the home of John Parkinson—now holds the two-story concrete 1948 Westinghouse Corp. offices and garage. Did the papers perhaps mean the southeast corner? Records indicate that a 1924 professional building was there, once: but that was designed by W S Hebbard. This may have been an unrealized project. (In 1924 the address is still listed as the Kensington Boarding School for Girls.)

1923 also sees the announcement for a store-apartment combo at the northwest corner of Sixth and Westmoreland, eight shops below and thirteen apartments (and one hotel room) above, with garages behind. This building, at 3109 West Sixth, stands and is in fine shape:

This building, at 3109 West Sixth, stands and is in fine shape:

the banner along the front reads “Immaculate Deco Must See!” I have to say, I’m tempted to see.

And if you true crime folks are nodding off:

At 3109, in his tiny apartment, authorities found a full laboratory, live pipe bombs, fuses, timing devices, gas masks, books on law enforcement, guerilla warfare, and military documents about munitions manufacture. After a pistol was found in his apartment at 3109, he remarked they’d better check ballistics for a match with the Steven Parent killing.

In 1976, more than two years after his arrest, Muharem remarked that officials hadn’t even found the explosives behind the medicine cabinet. It was true—they knocked out a false wall and the banner headline read “Chemicals Found in Apartment—Potent Enough to Blow Up Golden Gate Bridge.” He had “all but one” ingredient for a nerve agent (which he was picking up later that week), precurors for phosgene, and twenty-five pounds of sodium cyanide.

The tenants and landlady at the Borden Apartments—described as “scrupulously maintained”—said the Man in Apartment Five was a solitary but friendly fellow.

As a resident alien (of America), he was peeved that there were so many immigration hoops. But most of all because he had been humiliated at a dance hall, and demanded that the United States repeal all sex laws.

Then in 1924 there’s the announcement of the six-story apartment house as the southeast corner of Sixth and Benton. The building there, now, however, was built in 1952.

1924 is also the year of Dodd and Richards’ Mediterranean villa for New York attorney Samuel Untermyer out in Palm Springs. The Willows is still a prime Dodd and Richards destination.

The officers of the Pasadena Medical Building Company broke ground on the Tudor-Gothic eight-story Pasadena Professional Building September 13, 1924, on the corner of Herkimer (now Union) and North Madison. It opens July 11, 1925. It is owned and operated by forty-four prominent Pasadena doctors, built exclusively for the medical profession—even the ground floor is leased to a pharmacy and a nurses’ club. The $500,000 building is fitted with every possible modernity a medical building needs: automatic noiseless elevators, light signals instead of bells, special elevators designed for stretchers, sound-leadened floors, compressed air for dentists, an auditorium in the basement. (To tie Dodd and Richards back in to the Richfield, very vaguely, Carlotta Evans Thompson, 39, wife of Donald R. Thompson, former executive in the Richfield Oil Company, leapt to her death from the roof of Pasadena Medical, November 13, 1935.)

It opens July 11, 1925. It is owned and operated by forty-four prominent Pasadena doctors, built exclusively for the medical profession—even the ground floor is leased to a pharmacy and a nurses’ club. The $500,000 building is fitted with every possible modernity a medical building needs: automatic noiseless elevators, light signals instead of bells, special elevators designed for stretchers, sound-leadened floors, compressed air for dentists, an auditorium in the basement. (To tie Dodd and Richards back in to the Richfield, very vaguely, Carlotta Evans Thompson, 39, wife of Donald R. Thompson, former executive in the Richfield Oil Company, leapt to her death from the roof of Pasadena Medical, November 13, 1935.)

Here is a 1924 Dodd “teardown.” Apparently, though, it hasn’t been torn down just yet.

1925 sees the construction of another (lost) Hollywood Dodd and Richards store, this one at the southwest corner of Vine and Selma. The Moderne building north of ABC/TAV that was built as shops and a restaurant and apparently also served as the Santa Fe HQ.

The Moderne building north of ABC/TAV that was built as shops and a restaurant and apparently also served as the Santa Fe HQ.

In July of 1925, it is announced that Dodd and Richards are all set to design the new theater (for high-class legitamate plays) at the northeast corner of Eleventh and Hill on property owned by Edward Doheny. Dodd and Richards have been working on the plans for “several weeks” for Fred Butler and Edward (brother of David) Belasco. Again, the developers decided to go another way. The Morgan, Walls and Clements Belasco opens in 1926.

Lost to the Glendale Galleria.

Through 1926 to March of 27, we don’t hear much of anything from Dodd and Richards other than about the Architects’ Building. Then, in March, of 1927, ground is broken on George Washington High School which opens in time for the fall term, 1927.

Then, of course, there is the January 1928 opening of the Architect’s Building, a building about which your expertise is unsurpassed.

After the Architects’ Building, Dodd and Richards designed an auto showroom. At 1330 South Figueroa the Cardale Corp erected the one-story, trussless roof, eighty-foot clear window frontage building for lease to the J. W. Leavitt & Co. for their Willys-Knight and Whippet California distribution center. It opens December 15, 1929.

There were those of us who did our public grumbling, but to our eternal discredit, not loud or persistent enough. The Conservancy was busy with the Ambassador. The Art Deco Society, well, that was the same society that shrugged at the KEHE and loudly and soundly turned its back on the Mullen and Bluett. Landmarkable as car culture, Southland Deco, as Dodd & Richards, whatever, the kicker is it could have been adaptively repurposed from a parking lot and reused as a parking lot if left alone. Mysteriously, it is torn down to remain a parking lot. (Don’t even get me started about it’s neighbor to the north, the wonderfully intact 1913 Egan School of Music and Drama.)

There were those of us who did our public grumbling, but to our eternal discredit, not loud or persistent enough. The Conservancy was busy with the Ambassador. The Art Deco Society, well, that was the same society that shrugged at the KEHE and loudly and soundly turned its back on the Mullen and Bluett. Landmarkable as car culture, Southland Deco, as Dodd & Richards, whatever, the kicker is it could have been adaptively repurposed from a parking lot and reused as a parking lot if left alone. Mysteriously, it is torn down to remain a parking lot. (Don’t even get me started about it’s neighbor to the north, the wonderfully intact 1913 Egan School of Music and Drama.)

It remains as an auto dealership for decades until it becomes parking for the nearby Staples Center. It’s not torn down—cars just drive in and out of it. There is therefore no reason, ever, to tear it down. Of course, someone, in their infinite wisdom, did in fact tear it down in 2005.

The Willys-Knight/Whippet showroom is Dodd and Richards’ last building.

In March of 1930, there’s a note in the papers about construction starting on Dodd’s future residence: a seven-room Spanish in Playa del Rey, in the first of eight homes in a proposed twenty-four house development by the Dickson & Gillespie Corporation (because it’s a multi-unit corporate development, it’s unclear as to whether this is actually a Dodd design). The house is on sloping ground overlooking the sea, at 8252 Rees Avenue.

He never moves in.

He never moves in.

On June 14, 1930, Dodd dies at 1975 De Mille Drive. His services are held at the Little Church of the Flowers, Forest Lawn; give him a little wave if ever you pass by in the Great Mausoleum.

William Richards is seventy-four when he dies at his home in Pasadena in 1945. As he is at the time of his death president of Evergreen Cemetery, it stands to reason he’d be buried there.

After Dodd’s 1930 demise, Governor Young appoints H. C. Chambers, president of the So Cal AIA, to fill Dodd’s seat on the State Board of Architectural Examiners, where Dodd sat for many years with Austin and Parkinson.

Of course, after Dodd’s death, there are far few architectural embellishments in Los Angeles, of course his late 20s commisions abjured neoClassical stylings to fit the times; it would have been interesting, though, to have seen how he might have molded Spanish Colonial into Art Deco.

As far as the Prewar Guys go, Dodd and Richards have a higher-than-average survival rate.

A belated addition of the photo credits: I should mention that the images come from, as usual, the Los Angeles Public Library, USC and the California State Archives. Most of all I want to state that special thanks go out to jericl cat, from whose photostream on flickr we have the images of the garage on Figueroa.

Mr. Nathan Marsak:

I cannot say enough how much I enjoyed reading your text entries, photos and related links on the LA designs of William J. Dodd and William Richards. Besides the good data, your snappy humor was always entertaining. I especially liked the wisecrack about “the Conservancy cats” returning to their digs in Dodd & Richards designed buildings.

I was glad to see mention of the Palm Springs residence by D & R. Have you seen the ranch house at Los Rios Ranchos by Dodd? Sooo beautiful. There may be a Dodd design in Altadena, if you are interested in researching it.

Thank you for citing the Wikipedia page on Dodd which I authored and maintain. I will visit again and see what new data you publish.

Christopher White

University of Louisville, Louisville KY

To Mr. Marsak:

The design paternity of Ville de Paris is well established. It is a Dodd design.

See Architect and Engineer for September 1930 and, also, Withey’s Encyclopedia of American Architects Deceased from 1956; both attribute the VDP to Dodd and Richards. They relied on contemporary information and understanding.

Withey, in particular, was a LA identified architect himself and derived much of his information on Dodd from the papers of William Richards. Furthermore, though on its own it would not be enough proof, there is the LA Times article from Nov. 19, 1916 which announces the building plans for the Ville de Paris and includes a drawing of the building provided by the Dodd & Richards firm who were, the article states, handling its design; the 1916 drawing matches the existing building in most of its primary details except for prominent corner projections which must have been removed at a later point or never made it into the final blue prints and actual construction plans.

The Brockman is another issue. I will write here again when/if I can say something more substantial on its pedigree. Most accounts of this 1912 building’s origins attribute it to Harrison Albright and only a later, secondary addition to Dodd & Richards. [LA Times] “…a four-story structure to adjoin the present Brockman Building at Seventh and Grand on the south and to coast about $150,000. Dodd and Richards are…the architects.”

Respectfully, CTWhite.

Having given a more careful reading to the article you mention (the Times piece of November ‘16), I see D&R are indeed the patriarchs of the VDP plus the rest of that Strip of Seventh including yet another I hadn’t mentioned, and another, plus something across the street…I should really up and integrate all this into the post above, but we’ll leave that for the coffee table book. Anyway.

We’ll start with a shot of looking west down Seventh across Hill toward Olive. We’re between 1912 and 1917 because the two most prominent buildings are the towering Brockman, background left at Seventh and Olive, and the LAAC, right. Foreground right, across Hill, the bay window’d Victorian is the Dillon Building. The structure with the Omar Cigarette billboard, and the Zara Hotel—well, don’t park your trunks there, for they’re not long for the world.

1917 is our Big Year. Again, here is a shot of pre-Dodd and Richards Seventh:

And here is a reworking of the street, in a rendering by Arthur H. Stibolt.

We’ll work up the south side of Seventh beginning with the Huntsberger-Mennell. Yes, that giant building at the far left, above, is the H-M. It was built with basement and sub-basement to take multiple stories, and, as was often reported, they built two with the intention of constructing the rest in the future. Of course, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the H-M included, no-one got around to the fulfilling the original design.

Its neighbor is of course the Ville. Dodd and Richards design it as red pressed brick and terra cotta and, and as Christopher points out, its most distinctive design element are the ornamental towers at each corner. Here’s what really threw me, originally: sure, at some point someone nixed the towers, but while the fenestration appears essentially correct, with the arched top windows and all, you still can’t fit seven bays where only six can go.

Here’s another pic of the Ville de Paris. A little of it, anyway.

Now, uncharted territory. Sure, go downtown and there you are, so to speak. There’s the Coulter right next to the Brockman, just as it should be, but wait. Don’t forget the Dodd and Richards’ 1917 Henning Building (into which milliner Swobdi moved from Broadway) between the Coulter and the Brockman:

One can just make out the Henning hiding out there. Most notable is its roofline of steeply-pitched slate. It is finished in terra cotta and fitted with ornamental iron balconies. In this early-30s image, one can see that its built form didn’t quite get the Franco-Renaissance treatment. Where is the fourth-floor-as-gable? Never trust a rendering.

That brings us to the Brockman. In 1917 the entire ground floor of the Brockman Block was remodeled by Dodd and Richards for J. J. Haggarty’s New York Cloak and Suit Houase and, again, Dodd and Richards addition—an attached building for J. J. Haggarty, was to be bigger than it ended up being, in this case, it was envisioned as nine stories:

I mean, look at the size of that beast. Of course, it is eventually constructed as but a four-story building. How does one refer to this structure specifically? The Brockman Addition? The Haggarty Cloak and Suit Addition? The Times just calls it “The New York” which is pretty nifty.

So that’s the south side of Seventh, five Dodd and Richards in a row (should you count the Brockman Addition, which you should). Then, across the street and down a bit at the northwest corner of Seventh and Grand, the eight-floor Central Properties Building.

That’s six Dodd and Richards. Well, no, the Central Properties Building building was never built, as here’s a 30s shot of the northwest corner (on the other side of the 1912 Bronson Block AKA Brack Shops and the Quinby Bldg). And that’s no eight-story D&R. There’s a low-rise 1980 there now.

Now let’s throw something ELSE into the mix: Dodd and Richards’ Harris and Frank building, at the northwest corner of Seventh and Hill.

That’s the tale of the five-in-a-row, literally and chronologically, Dodd and Richards along Seventh. Plus the sixth and seventh, unrealized…at least as best I now understand it! –Nathan

Mr. White,

Very glad you enjoyed my post, and especially that you liked the wise crackery. Sort of the West Coast version of your marvelous Wiki page–where such effrontery is frowned upon!

(A lady-friend years back hailed from Salem, so of course we stayed in Louisville, and I immediately wanted to stay. I didn’t realize a decade ago I was in Dodd Central.)

You know, I had scribbled something in my notes about the 1918 Howard Leland Rivers house in Oak Glen as it was mentioned in the ArchitectsDB, but just now found the image on p. 26 of Arcadia’s book on Oak Glen/Los Rios Rancho. I’d go photograph it myself, though it’s a bit far afield.

Altadena is (comparatively) my neck of the woods, though—where is this mysterious Dodd?

Thanks again for your interest and comments…I think I’ve got the Huntsberger down to the Brockman figured out (up to and including their neglected Henning Building), but then there’s the Harris and Frank across the street…hmmm…more soon.

Nathan

William J. became acutely ill while traveling with his wife Ione in Europe. He returned to the states and died within a week in an LA hospital. That Ione continued the European tour (with her sister) could imply that William’s sudden sickness was not a cause for alarm when it overtook him. His funeral was delayed two weeks to accommodate Ione’s return to LA from abroad. 1975 De Mille Drive does seem to be the Dodd residence in June of 1930.

Dodd had made himself a millionaire by the time of his death but he was over-extended in real estate holdings and risky oil speculations on the eve of the stock market crash. Tracking his widow’s attempts to liquidate assets and handle outstanding debts, foreclosures and liens (borrowing from wealthy friends), as well as her involvement in a decade of legal fallout from Los Angeles oil well scams, this researcher infers a sad, last chapter to the brilliant Dodd legacy adrift into obscurity. All of this is to say, I am so very excited by the growing interest in Dodd’s work that Mr. Marsak and this OnBunkerHill.org readership appear to be creating among Los Angelenos. Could this become a buzz among the "Conservancy Cats", too?

Scroll up there to 1924 to the bit about the Willows.Â

Truth is, the image I’ve included is not an image of the Willows proper, but of the O’Donnell house, built for Thomas O’Donnell. The official historic designation indicates its architect as William Charles Tanner.Â

The Willows itself, while a Dodd and Richards, was not built for Untermyer–he bought it a year or two afterward.

Or so says Tony, a contributor from Desert Hot Springs.  Now Tony, to whom I owe the greatest of debts for having pointed these facts out to me, also notes that there exists no actual documentation indicating that neither Dodd nor Tanner had a hand in either structure: the attributions have been passed down as word-of-mouth. The nascent theory, still in development, is that Tanner, who was more artist than architect, went to work on the O’Donnell and Dodd was brought in to flush things out.

O’Donnell was a king among California crude producers. Not sure if he was an Uplifter, but Harry Marston Haldeman, president of LA’s Pacific Pipe and Supply and rabid antiCommunist, was a founding Uplifter in 1913. Haldeman was also part of an investment pool that bought into Julian Pete petroleum stock in 1925, a Ponzi scheme so odious that it led to the creation of the SEC (fat lot of good that did). Cecil B. DeMille was also part of the "Million Dollar" cabal, indicted for embezzlement and usury, and he lived up the road from Dodd. Dodd, upperworld as underworld, Uplifters, famous neighbors and usurious hydrocarbon stock schemes, all woven together…somehow. There’s and Ellroy novel in here.

The reference and photos of George Washignton High School, in the Marsak coda on Dodd & Richards, reminded me of another significant school design in LA by Dodd & Richards. (btw: Richards was essentially an engineer, the design aesthetics were of William James Dodd’s imagination.) Mr. Marsak should include in his excellent entries a photo of the Jacob Riss Vocational School for Boys which this Kentuckian believes exists still as an active school district entity. To paraphrase Marsak: as Pre-War architects go… D&R rate very high on the survival scale.

Riis Vocational, eh? Well, let’s go down and take a look…

Ah ha! Looks Doddsian.

Found one photo (LAPL):

You can see where the path was across the grass in both images, though the arcade is gone:

I’m unclear as to when exactly this building was erected. The first mention I can find of the school? The Jacob Riis track team copping honors in a triangular meet on the Riis cinder path, trouncing Gardena and Bell, and coming within one-fifth of a second from breaking the Marine League record in the half-mile relay, February 25, 1928.

The school has had a heavy stucco application, that tile is all wrong, and is suffering the repeated application of geegaws (though I should be thankful, no supergraphics or cell-phone towers).

A little more history of the school, just for kicks.

Riis is the alma mater of, for example, Angel Padilla and Henry "Hank" Joseph Ynostroza, two of the defendants in People v. Zammora, aka the Sleepy Lagoon.

It began in March, when students from both schools held beach parties in the Hollywood Riviera sands. Cross words were exchanged, and that led to a telephoned challenge from one Leuzinger pupil to two from Riis for a gang fight on the same beach. Later other Leuzinger pupils overruled the idea, but when the Luezinger challenger passed the word along, the Riis boys refused to ignore the challenge. (After all, who backs out of a gang fight challenge you’ve made…on the telephone?) First the Riisians headed to the beach, but found nary a Leuzinger, and so sought their opponents at Crenshaw/Compton, where they pounced and the camps battled twice; four Leuzingers got the beatdown in the first fight and in the second, Howard J. Edison, 18, was was treated for body blows and a cut over the eye. Nine Riis students were jailed at the Sheriff’s Lennox Station and booked on assault and battery and conspiracy to commit a disturbance.

Riis was noted for its low graduation rate. In 1956, when graduation rates for high school seniors numbered in the hundreds per schools like Franklin, Jefferson, Manual Arts and Marshall, Riis graduated, uh, eight. In 1963 one of those yearly handwringers attacking the school dropout problem addressed Riis in particular:

May 1965 sees Jacob Riis special education high school will move into three floors of the Wiggins Building at 1646 South Olive.

The Dodd building on 69th, it is announced in November 1965, is to be renamed from Jacob Riis to Mary McLeod Bethune. $2.4 million is to be spent building new structures for the campus, though retaining many of the old as it is converted and rehabbed from a senior high to a junior. The architect is Carey K. Jenkins, who at the time is embroiled in a controversy involving over the $16 million junior college at Imperial and Western, wherein the Rev. James E. Jones wanted favored African-American Jenkins as architect and the Board of Education favored Honnold & Rex; the Board finally decided just to compromise and pair the concerns.

One last thing, just ’cause we got it.

Though the name has been changed, perhaps it’s the ghosts of former Riis students that cause all the underperformance and (alleged) behavior problems at MMB. That would be cool.

By the tent peg of Jael! Wowza! Christopher White of the University at Louisville–the gent who hipped me to the February 1927 reference to Riis Development in the Times–sends in this:

Like their George Washington at Denker & 108th, here’s another D&R school that’s lost its tower. Â

Note how they’ve sort of "hollowed out" the tower portion, completely eliminating the Romanesque arches. I’m having visions of colorful tilework, ropetwist columns, intricate leaded glass in the fenestration–if not stained–employed in the tower. Not all at once, though. Even I have my limits. (But there’s a pile of crisp 8x10s out there, somewhere, that explains all.)

When I was researching Dodd in the UCLA Young Special Collections Library, a few years ago, I came across correspondence between Dodd and Lloyd Wright Jr. Junior was landscaping for Dodd on residential projects (including Dodd’s own 5226 Linwood Drive residence being built at the time) and later did additions to some other Dodd structures.

Junior makes two references to working at a Dodd project in Altadena. There is a 1920 citation about landscaping the property for Dodd and then a 1928 citation about doing an addition to the residence on the same property. Remember those dates.

In both citations the property is identified as the home of Mr. and Mrs. Frank H. Upham and the address is consistently given as 1943 Mendocino in Altadena, and the citations are in a file that is exclusively work done for Dodd & Richards.

I believe the property still stands at the intersection of Mendocino Lane and Glenview, but now has a street number of 1955 Mendocino Lane. However, the earliest, nonauthoritative dates I have found online for that house is 1926 and 1928 with builders listed as Glover and Kauth but the designer is unknown. From my vantage point in Louisville, looking at satellite photos, the house appears to be a compound so it could have been worked on at different times by different designers.

There you have it.

See LA Times, Feb. 8, 1927 article about new trade schools being built.

I can send Nathan a very grainy picture of the old Riis school if e-addresses are exchanged.

Mine: christopher.white@louisville.edu

There are noticeable differences in the photograph from what remains of the structure.

Most missed is an arched 1st-floor entry under a 2-1/2 story tower with a kind a sleek, streamlined deco aspect and two additional arched windows on second floor of tower.

Thanks for that–don’t know how I missed it, probably because in the 2/27 article the development school is termed "Jacob Riis Junior High" and among the variety of words I was entering into the search field I think I didn’t quite put in that combo…

Assuming you’ve read, below, the tale of D&R you marveled of course at the Mission Playhouse. What’s especially cool about the Playhouse is that it’s the biggest thing around. Its surroundings are bucolic, if not positively idyllic—and it’s only about twenty-five feet high, and that’s Missiony gabled roofline (ok, a "positive idyll" is hyperbolic and we’re at roughly thirty feet if you want to quibble about the auditorium in back).Â

But now, some characters called TSCP Investment are looking to skew the Mission District landscape, erecting a four-story, block-long condo/hotel/restaurant/retail complex across the street (basically across the street, a little to the NW) which rises in part over sixty feet high. This thing is in direct violation of the City’s Master Plan for the district, but the City was quick to grant them variance. A “variance,” for those of you who don’t know, is a word that means “don’t bother pretending there’s a law, kids, because we can do whatever we want.” That the City would bend over for a developer isn’t so much shameful as it is typical. It’s also a little surprising, in that nearby we’ve seen the erection of the twenty-two unit “Gardens at Mission San Gabriel”, and eleven unit “Mission Villa” project, which include 5,300 sf of retail.

Because this is OBH, I won’t argue environmental impact and that jazz; I’ll just say that, in choosing to ignore City zoning laws (specifically, floor-to-area ratio and height limit codes) and abjure the City Mission District Plan, and push for the historic neighborhood fabric to be negatively impacted (specifically, our friend the Dodd and Richards Mission Playhouse), the City must be taken to task. As much as I’d like to storm Council chambers and start swashbuckling, who’s as young as they used to be? Therefore, please sign this nifty petition found online:

CLICK HERE! SIGN THE PETITION TO PROTECT THE SAN GABRIEL MISSION DISTRICT!

As of this writing, they have 7.3% of the signatures they’re after. Add yours! Tell a friend! Don’t let a Dodd be dwarfed!

Hi there, – Congratulations on your thorough research! I believe we have a Dodd and Williams office building in Long Beach, commissioned by the National Cash Register Co. It is being restored and repurposed for an Art Exchange. Unusual windows, probably plastered over in the 1930s, hint of a Beaux Art or maybe even Spanish facade. Check the SWB&C Oct 24, 1924, in Long Beach Notes. Any additional details you might have will be really appreciated by the non-profit that is restoring the building. I take it D&W did not leave an archive, residing nicely at UCSB?