It’s not an Edwardian octoplex full of grime and grifters. It‘s not even on Bunker Hill. But we‘re going to tell the tale of the Architects‘ Building, and if not to you, faithful OBHer, then to whom?

All and sundry weep for the Richfield. It‘s not altogether true that everyone turned a blind eye during its”68-9 demo. Even the Government knew enough to come on out with its Instamatic and take lots of snaps.

The November 1968 Times article “Black and Gold Landmark: End Arrives for LA‘s Richfield Building” discusses those architecture students who believed the structure a remarkable example of “Jazz Moderne” worthy of preservation.

And the only mention of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth (which by 1968 had been renamed the Douglas Oil building) and which shared the block with the Richfield was as such:

”¦and that was the end of that. According to Cleveland Wrecking‘s general manager, the million-dollar site clearance project, of the block bordered by Fifth, Flower, Sixth, and Figueroa, was the largest ever undertaken in the West.

What is this Architects‘ Building of which we speak? Who architected this interbellum edifice?

Downtown is very nearly defined by Parkinson, and you can‘t mention LA without Morgan, Walls & Clements (Stiles sitting in the softest spot of this writer‘s heart), and if I mention Walker and Eisen, you‘ll say Yaaay! and I‘ll agree, and we‘ll high-five, and then get cut off and kicked out of wherever we are. It sure is swell to take those Conservancy tours and see all these places, but when the Conservancy cats go back to their digs, they return to a Dodd and Richards.

And you say, who?

William J. Dodd, student of Jenney and Beman is one of the great Midwestern architects. He came to California and is credited–though scholars still dispute to what extent–with a portion of Julia Morgan‘s 1914-15 Examiner Building. This he did with his partner at the time J. Martyn Haenke. In 1916 he partners with engineer William Richards. They produced so many an important Los Angeles structure that I will at some point in the near future add their full history as a comment appendage to this text, to keep from having too many appetizers before our twelve-story entrée.

We’re talking about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa, not to be confused with our friend on the kitty-corner to the northwest, the Monarch Hotel.

The first rumblings about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa come in February 1926, when mention is made of preliminary plans and lease negotionations for a million-dollar skyscraper to house LA‘s building trade. Sponsoring the project are Morgan, Walls and Clements, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, Webber, Staunton and Spaulgin, Carlton Monroe Winslow, Elmer Gray and McNeal Swasey.

The big announcement is made in February 1927 about the $650,000 height-limit to be built on the southeast corner of the Fifth and Figueroa. To be known as the Architect‘s Building, after New York and Chicago, it would be the third of its nature in America: a whole structure exclusively devoted to the various branches of the construction industries. It is to be of a “modified Italian” architectural treatment according to the associated architects drawing up the specifications: Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carleton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson.

Twelve stories high, with a site of 60 by 156 feet, it is to be of steel reinforced concrete, 143 offices, its exterior finished in plaster with cast-stone trimmings. Its seven upper floors of the building are to be leased to prominent architects, its first floor and mezzanine to be occupied by the Metropolitan Exhibit of Building Materials–a massive exhibit of every branch of the building industry, renamed the Architects‘ Building Materials Exhibit.

By November of 1927, the building was nearing completion. Preston S. Wright, president of Wright-Aiken, owners of the AB, ran down some of the tenants: Rapid Blueprint Company; D. C. Writhg, insurance; E. E. Holmes, insurance; William Simpson Construction Company, builders; Brian D. Seaver, attorney; and architects D & R, Coate, Johnson, Winslow, and William Lee Wollett.

816 opens in January, 1928. It came in at $662,000.

The depression would not be good to the Architects‘. It was foreclosed on its $360,000 outstanding bonds in February 1933. It was put under federal receivership and forced into a court-ordered sale, which didn‘t occur until May of 1938, when an F. V. Fallgren and associate could pony up the 300k to a trustee representing the bondholder‘s committee.

The Architects‘ Building survives just fine through the 40s and 50s.

One bit of drama: Evans Erskine, 34, a jobless Air Corps vet, figured that 1955 would be Year Last. He climbed to the ninth-floor fire escape of the Architects‘ Building and hoisted himself over the railing. Richard McGowan, a controller for Dames & Moore Civil Engineers, ran down the hall and and grabbed the hands of the nattily dressed, ledge-teetering Erskine poised 100 feet above Fifth Street. Here, McGowan reenacts his daring hand-grabbing:

In 1959 it is purchased by Douglas Oil, a southern California independent who run three refineries and 300-some gas stations in the Southland. It remains the Douglas Oil building despite Douglas‘ purchase by Continental Oil (AKA Conoco) in 1961.

It‘s the 1960s when the folk in 816, heck, the building itself, could hear the dirge of doom wafting on the wind. Listen, it‘s coming from over by the Richfield building.

Richfield, another oil company, who owned that big ol‘ black and gold tower to the south, had merged with east coasters Atlantic Refining in 1966. Richfield had already begun buying up the block for piecemeal parking, and as Atlantic-Richfield Co. they purchased the whole kit. And kaboodle. That called for the end of the Architects‘, as ARCO intended to build not one but two Miesian towers (though their New York twin-tower counterparts broke ground four years earlier, there appears to be an aesthetic epoch between AC Martin’s work and Yamasaki’s tube-frame twins of lower Manhattan, whose postmodern sensibility stems from a neo-Gothic use of aluminum).

1967, and all‘s well:

1969, during the demolition. The Architects‘ Building, now one-fifth off! The Richfield, now with two-thirds less Richfield!

1970, towers going in.

Left to right, the Tishman Building (Victor Gruen, 1960, though you know it like this), Glore Forgan Staats, the Gates Hotel (now a fine Brooks Bros), St. Paul‘s Cathedral (razed), the Hilton (note how it changed from the Statler to the Hilton between 67 and 69), the Jonathan Club , the Carlton Hotel (razed), Caldwell Banker.

Below, today. Note the wee bit of the Jonathan peeking out.

The ARCO Towers still stand in all their glory. For now.

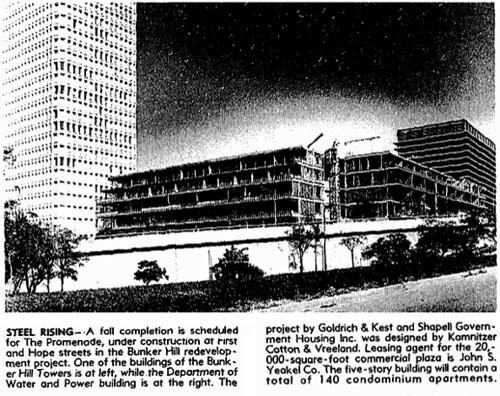

Another shot of the demolition. The Sunkist, Engstrum and Edison line Fifth. The Telephone Tower on Grand. In the distance, left, Bunker Hill Towers going up.

A mid-60s aerial. Central Library bottom right. The Sunkist at Fifth and Hope. Halfway up Hope behind the Sunkist, the tiny Sons of the Revolution and the Santa Barbara. The big apartment building at the southwest corner of Fourth and Hope was the Barbara Worth.

Of course we’re not getting away without the requisite model and Sanborn additions:

Note how Fourth Street ends at Flower. Compare to the 60s aerials which indicate the magnitude of the 1954 Fourth Street Cut.

Just to clear up one bit of confusion. Despite early mention that this building was to be of the combined effort of Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carlton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson”¦it‘s a Dodd and Richards. Even Adrian Wilson, who in April 1967 wisecracked “I hope our new location won‘t be so temporary” in an article about his having to move out of the AB after thirty-nine years, remarks that Dodd and Richards designed the building–and he should know, the plans for 816 are inscribed with his own initials, as he was their draftsman before he hung out his own shingle when the building opened in 1928.

Clockwise from the south: Sixth, Figueroa, Fifth, Flower:

That then is the tale of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth. Remember the diaspora the next time you‘re in the neighborhood.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library photo archive, University of Southern California, and Arnold Hylen and William Reagh Collections, California History Section, California State Library

February 27, 1911. It‘s 9:30am, and

February 27, 1911. It‘s 9:30am, and